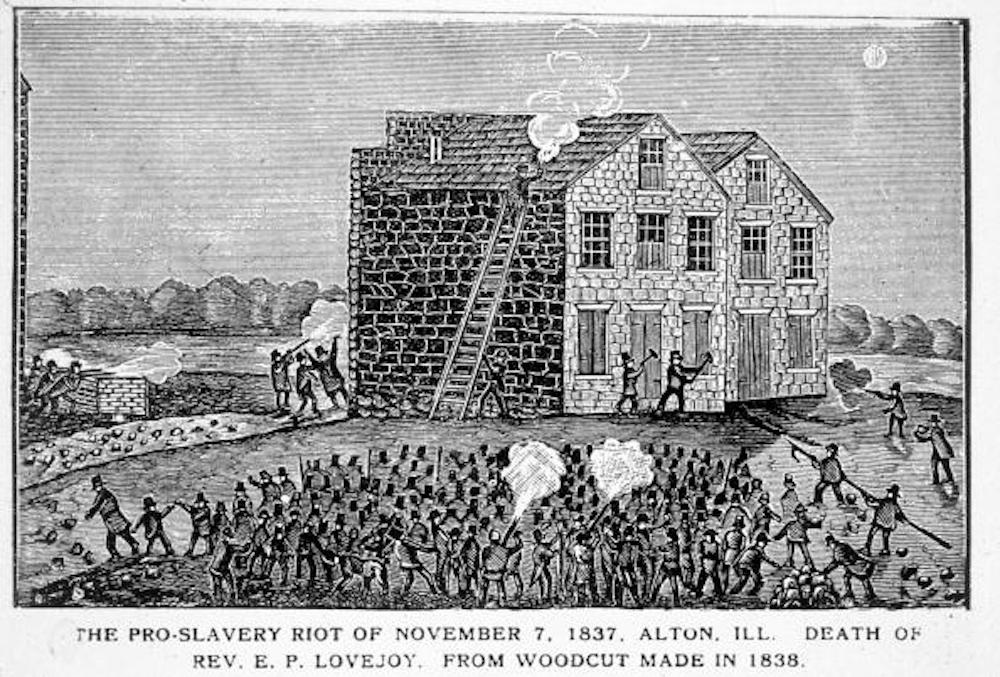

The attack on the home of the abolitionist newspaperman Reverend Elijah Parish Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois, by a pro-slavery mob

"First to Fall: Elijah Lovejoy and the Fight for a Free Press in the Age of Slavery" by Ken Ellingwood

In his newly released monograph,”First to Fall: Elijah Lovejoy and the Fight for a Free Press in the Age of Slavery,” former Los Angeles Times correspondent and author Ken Ellingwood examines the free press during a time of expansion for slavery in the United States. It focuses on the life and work of Elijah Parish Lovejoy, a Presbyterian minister who worked at abolitionist papers in the Midwest. In May 1836, the paper he edited, the St. Louis Observer, was destroyed by a pro-slavery mob. He soon moved to nearby Alton, Illinois, and launched the Alton Observer. Lovejoy died a year-and-a-half later in an attack by another pro-slavery mob in Alton in November 1837.

In this excerpt from the first chapter, the author recounts Lovejoy’s move from St. Louis to Alton in 1836.

The evening after the riverbank mauling of his printing press, Lovejoy was invited to attend a meeting with some of Alton’s most prominent citizens. It was an unofficial gathering but, as with many such community meetings across America during the antebellum era, one that could end with decisions. The Altonians wanted to have a conversation with this fellow who had been all but chased from a neighboring state and now was the focus of mayhem in their own. They would come to a few understandings. Understandings such as there wouldn’t be much tolerance for anyone seeking to stir up passions over the issue of slavery. Among the wary attendees at a newly built Presbyterian church was the future mayor John M. Krum, an attorney in his mid-twenties who, like many of Alton’s leading lights, had migrated from New York a few years earlier. Several others who would later prove to be among Lovejoy’s staunchest allies also showed up. There was Amos Roff, the owner of a store that sold wood stoves, grates, and hardware, and the Reverend Frederick W. Graves, an Amherst College graduate who was minister at the First Presbyterian Church in Alton. Both would remain at Lovejoy’s side through the months of trials that lay ahead.

Lovejoy was asked to describe his plans for setting up the Observer in Alton and to make clear to the assembly just how deeply he planned to delve into the slavery issue. Lovejoy was in a delicate position here: he was in a new town, standing before a church full of residents — many of them strangers to him — who would determine whether his decision to come to Alton had been wise or foolish. They represented a kind of jury, and his answer mattered deeply. Poised before the group, Lovejoy cut a hardy figure: a man of medium height, muscled, with a dark complexion and piercing black eyes.

The editor spoke. His main objective was to edit and publish a religious newspaper, Lovejoy began. He then turned to the issue that was on everyone’s mind: slavery. “When I was in St. Louis I felt myself called upon to treat at large upon the subject of slavery, as I was in a state where the evil existed,” he explained. Lovejoy said that as a Missouri resident, he had felt a “duty” to inject the topic of slavery into his weekly columns there. But he denied being an abolitionist, and made the point that he had even previously clashed with them from time to time. “I am not, and never was in full fellowship with the abolitionists . . . and am not now considered by them as one of them.” Now that he had moved to a “a free state where the evil does not exist,” Lovejoy continued, “I feel myself less called upon to discuss the subject than when I was in St. Louis.”

The editor’s remarks would surely have had a comforting effect on the men inside the church: There was now little reason to expect that Lovejoy’s newspaper would become a source of controversy. He had said so himself — slavery might be a hot topic on the far side of the Mississippi, but what need was there to discuss it in Illinois, a free state? Some of those present at the meeting would go even further. They chose to hear — and, later, to portray — Lovejoy’s words as a guarantee, a pledge. To their ear, Lovejoy had promised that he would keep his little newspaper free of all talk about slavery.

But others who were listening to Lovejoy’s presentation, including Roff and Graves, heard no such thing. In fact, as they and others would later recall in a signed declaration, Lovejoy closed his remarks with what ultimately would be preserved as a full-throated defense of his right to publish. “But gentlemen, as long as I am an American citizen, and as long as American blood runs in these veins, I shall hold myself at liberty to speak, to write, and to publish whatever I please on any subject,” Lovejoy concluded. Lovejoy would have occasion to repeat similar sentiments many times in print and speeches, but the clashing recollection over the substance of his comments this evening later came to take on outsize significance.

Was Lovejoy telling the truth? Or was he an abolitionist? Did he intend to remain quiet on the sensitive matter of slavery? Or was he fooling himself — and others — by suggesting that he would somehow feel less need to decry an institution he abhorred simply because he had crossed a state line, even one separating North from South? Lovejoy biographers who have parsed his words from the church gathering generally agree that the editor probably made no explicit pledge to remain silent, but may have conveyed a message the crowd was too eager to hear. The historian Merton Dillon, the most rigorous of Lovejoy’s earlier biographers, says that Lovejoy’s comments were “filled with half-truths and ambiguities,” and reflected a considerable lack of self-awareness in failing to realize just how far down the road toward abolitionism he had already traveled. When the Altonians who listened to Lovejoy then voted to approve statements vowing to preserve law and order and to help him replace his ruined press, they clearly were not acting as if they had an abolitionist in their midst — certainly not one who would use a newspaper in Alton as a vehicle to mobilize antislavery opinion. “When the people of Alton later discovered that he continued to oppose slavery,” Dillon writes, “their wrath toward him became so much the greater because they believed they had been deceived. Lovejoy, it seemed to them, had abused their hospitality and broken a solemn pledge.”

For his part, Lovejoy read the group’s declared stand against aboli- tionism as “all for effect.” In his July 30 letter to Joseph in Maine, Lovejoy stood by his assurances. “I told them, and told the truth, that I did not come here to establish an Abolition paper, and that in the sense they understood it, I was no Abolitionist, but that I was an uncompromising enemy of slavery, and so expected to live, and so to die,” Lovejoy wrote.

In that single sentence, the editor had put his finger on one of the fundamental quandaries dividing antislavery Americans at the time, as organized efforts to bring about the emancipation of the country’s more than two million slaves began to sprout in the Northern states. As Lovejoy knew well, it could be problematic in certain places to openly express moral dismay over the enslavement of fellow humans. But it was quite another thing to be identified with abolitionists, whose incipient agitation on the slavery question was often attacked — even in the North — as the work of madmen and insurrectionists.