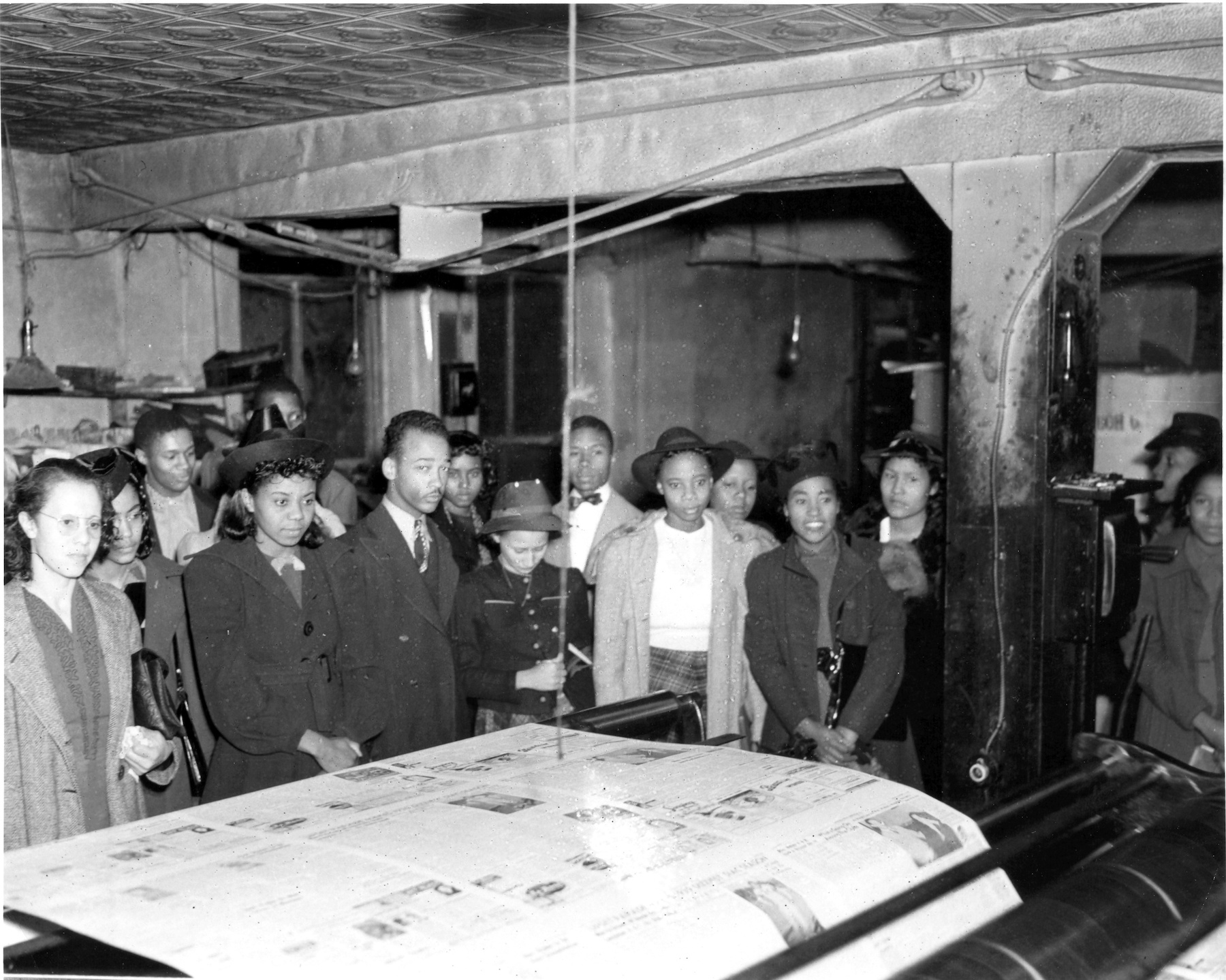

In this undated 1940s photo, students tour the printing plant of the Atlanta Daily World, Atlanta's oldest Black newspaper. During the Jim Crow era, Black newspapers played an important role in challenging white supremacy

“Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America,” edited by Kathy Roberts Forde and Sid Bedingfield and set for publication by University of Illinois Press in December, explores the press’ historically important role in the Jim Crow South. At the same time that white publications sought to protect white supremacy, the volume argues, the Black press defended against such racist practices in pursuit of a fully realized liberal democracy. In this excerpt from the volume’s conclusion, “Journalism and Jim Crow” considers where the press stands in the face of racial violence today:

"Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America"

From the founding of the first Black newspaper in 1827 through at least the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, the Black press and the white press operated in largely separate Black and white public spheres in the United States. Perhaps an integrated press would have paid attention to the systemic racism that greeted African Americans making the Great Migration from the South during the early to mid-twentieth century. Such a press might have documented residential segregation across the United States and shown that it was not simply the result of individual choices, the prejudice of realtors, and discriminatory mortgage lending practices known as redlining. Rather, as Richard Rothstein brilliantly shows in “The Color of Law,” it was the result of systematic public policy at the local, state, and national levels. These policies were unconstitutional violations of various prohibitions in the Bill of Rights against government treating citizens unfairly. An integrated press might also have noted anti-Black provisions and practices in critical New Deal public policies such as the Wagner Act and Social Security Act of 1935, as well as the Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933. It might have exposed and fought more effectively against school segregation and gerrymandering meant to weaken Black voting power in the North and West. It might have lifted the veil on what Brian Purnell and Jeanne Theoharis have called a Northern Jim Crow that “hid in plain sight.”

It is much harder to imagine an integrated press in the South before the victories of the civil rights movement. Despite Henry Grady’s soaring rhetoric and industrial fantasies, the New South turned out to be a weakly industrialized syndicate of Southern states built on racial caste and terror, a near-totalitarian society operating for generations within the greater United States. Like all totalitarian states, it maintained power through a news system essentially controlled by those in power, with white press leaders working hand in glove with the Democratic Party to craft and maintain white supremacist political, economic, and social orders. These white leaders built a world that was inhospitable to Black aspiration, opportunity, and dignity, and they built it on stolen or exploited Black labor. It was a world that silenced a generation of Black journalists in the South who tried to keep this world from being built. As Blair LM Kelley observes in chapter 10, the personal, collective, and historical costs of this silencing are incalculable.

Yet it’s a calculation any American interested in repairing and advancing liberal democracy would do well to ponder, especially given the discomfiting reality that every generation of Black journalists has struggled to be heard in America beyond the Black public sphere. In the summer of 2020, journalists across the country—indeed, across the world—covered the Black Lives Matter protests that blanketed the United States and spread to countries on every continent. Prominent Black journalists in the United States, many of whom came of age covering the Ferguson, Missouri, protests in 2014, publicly criticized their newsrooms for hewing to notions and practices of normatively “white” objective journalism that often prevented frank, clear descriptions of racism or, in the case of Senator Tom Cotton’s op-ed in The New York Times calling for the use of military force to put down protests, allowed racist views to be aired in elite opinion pages. Some Black journalists who commented on anti-Black racism on social media were prevented from covering the protests, to begin to reckon with and dismantle structural racism in their own newsrooms.

Some historically white newspapers have apologized for their roles in building and maintaining white supremacy. In 2005 the Raleigh News and Observer apologized for its central role in the Wilmington Massacre of 1898. In 2006 the paper published a special insert detailing its role in the corrupt North Carolina election of 1898 and the violent overthrow of Wilmington’s biracial Fusionist government. In 2018, when the National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in Montgomery, the Montgomery Advertiser apologized for its past racist coverage of Black life and indifference to lynching. In 2019 the Orlando Sentinel apologized for its racist coverage of the Groveland Four rape case in the mid-twentieth century. In 2020 the Florida Times-Union apologized for failing to cover a vicious 1960 Klan attack on teenage lunch counter demonstrators with ax handles. (However, the paper failed to mention its support of Flagler’s racist labor practices at the turn of the century.) Also in 2020 the Kansas City Star apologized for its prodigious history of anti-Black reporting, including its support of redlining and countenance of racial violence. More apologies will almost certainly appear, but apologies are hardly enough.

What will news leaders and journalists do about the racism that continues to structure American newsrooms and news content, especially coverage of Black life, the criminal justice system, policing, racial justice, and Trumpism’s illiberal and racist values and political programs? What are the possibilities in our own moment that journalism can be remade to serve the values of a multiracial and just democracy, thereby perhaps even remaking the country itself as a “new America?”

From “Journalism and Jim Crow: White Supremacy and the Black Struggle for a New America,” edited by Kathy Roberts Forde and Sid Bedingfield. Copyright 2021 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.