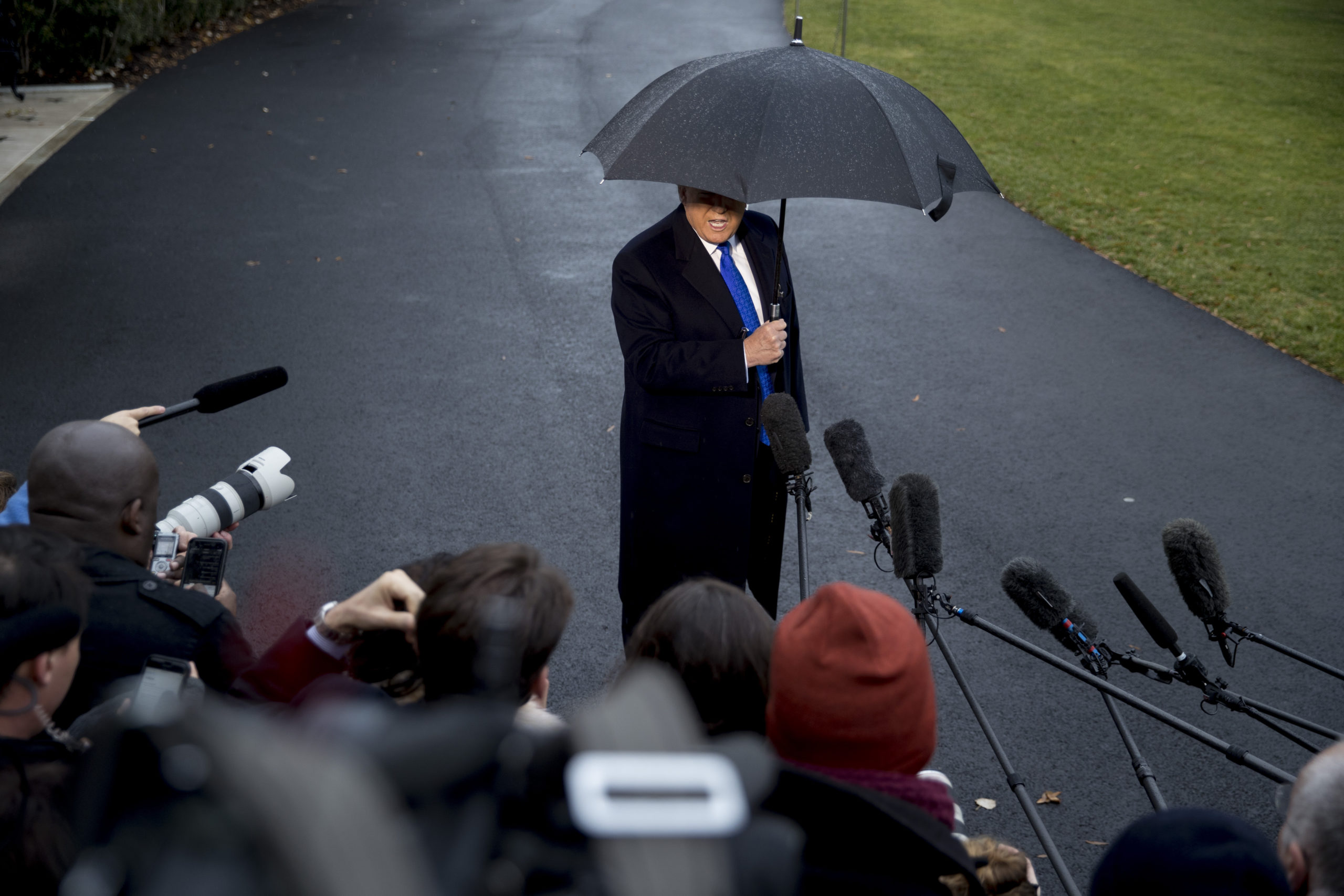

President Donald Trump speaks to members of the media before boarding Marine One on the south Lawn of the White House, Dec. 2, 2019

The Trump years marked a soured relationship between the press and the presidency: Misinformation ran rampant, the partisan divide cut deeper, and the White House routinely launched attacks against journalists. All the while, the coronavirus pandemic ravaged communities across the country, protestors demanded racial justice, and the effects of climate change grew more catastrophic. The Trump presidency, however, was not the first marred by crisis nor the only to harbor a challenging relationship with the media. Jon Marshall’s new book, “Clash: Presidents and the Press in Times of Crisis,” published by the University of Nebraska Press in May, explores how crises have shaped how U.S. presidents interacted with and utilized the press.

The following excerpt provides an overview of how different presidents navigated their relationship with the press, and highlights the important role journalists have in holding presidential administrations accountable:

"Clash: Presidents and the Press" by Jon Marshall

Starting with the nation’s early years, presidents have frequently attacked, restricted, manipulated, and demonized the press in order to strengthen their own power. The Adams administration used the Sedition Act to jail editors, Lincoln allowed newspapers to be shut down, and Wilson and George W. Bush used misleading propaganda to promote going to war. The Wilson and Obama White Houses sought to intimidate the press through the Espionage Act. Nixon sent Agnew to give speeches describing the press as a treacherous enemy. Trump amplified this dangerous hostility by his glorification of violence against journalists and his characterization of the press as un-American.

While Trump and other leaders menaced journalists, technological advances fragmented the media and enhanced presidents’ ability to avoid the White House press corps and communicate directly to the public. Roosevelt used radio, Kennedy and Reagan mastered television, and Obama turned to social media to reach mass audiences without relying on the gatekeepers of the press. Clinton and Obama used TV entertainment and talk shows for the same purpose. Trump deployed Twitter successfully to set his own agenda and often overwhelm the ability of journalists to put his presidency in perspective.

Trump, however, never learned the lesson that presidents who nurture respectful relationships with reporters have more long-term success than those who don’t. “Some presidents are reasonably secure in themselves, or in the affection of the voters,” former White House reporter James Deakin observed. “As a result, their dealings with the news media, although highly important, do not become an overriding or neurotic preoccupation.” Lincoln, FDR, Kennedy, and Reagan had that kind of confidence along with good senses of humor. Adams, Wilson, Nixon, and Trump certainly didn’t.

Although sometimes sloppy, partisan, and sensationalistic, journalists have often courageously served the public when covering presidents despite formidable forces trying to stop them. Matthew Lyon went to jail rather than muzzle his criticism of John Adams. Victor Berger went to prison because his newspaper opposed Wilson’s war plans. Katharine Graham supported Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s investigations of Watergate despite Nixon’s attempts to punish the Washington Post. Knight Ridder reporters bravely and accurately challenged Bush’s misleading rationale for going to war in Iraq. And many journalists continued to question and investigate Trump in the face of furious threats against them.

Sometimes pressure on presidents has come from social movements that have harnessed the media to advocate for dramatic policy changes. The abolitionist press proved this. Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Elijah Lovejoy, and other abolitionist writers spread their descriptions and denunciations of slavery through newspapers and pamphlets that were passed from person to person, eventually influencing Lincoln. Other social movements, such as the long campaign to win voting rights for women, employed similar tactics. The activists of the Black Lives Matter movement, some of them acting as citizen journalists, have used social media to share videos, photographs, first-hand accounts, and other information about police violence. Although most aren’t employed by news companies, their deft handling of media allowed their message to reach millions of people, spurring professional journalists to deepen their coverage of the Black Lives Matter cause. Trump mocked the Black Lives Matter movement, but now it is influencing the Biden administration to take steps to reform policing and reduce systemic racism.

Since George Washington’s second term, partisans in the media have frequently attacked presidents and other politicians. Writers such as William Duane and James Callender showed how vicious the press could be during the Adams administration. William Randolph Hearst, Henry Luce, Col. Robert McCormick, and Charles Coughlin ferociously attacked Franklin Roosevelt. Partisanship has escalated in recent years following Reagan’s destruction of the Fairness Doctrine. Powerful right-wing media—unmatched by anything nearly so strong on the left—intensified the nation’s polarization during the Clinton, Bush, Obama, and Trump presidencies. Talk radio hosts, conservative cable channels, and websites such as InfoWars spread conspiracy theories and abetted Trump’s effort to overturn democracy.

This toxic partisanship has encouraged a growing disregard for the truth by some recent presidents and their media allies, eroding trust in democratic government. Nixon deceived the public about Watergate, Reagan about Iran-Contra, Clinton about his extramarital affairs, and Bush about the Iraq War, to name a few. Trump trampled the truth at a pace that far surpassed his predecessors. As historian Timothy Snyder notes, “Post-truth is pre-fascism, and Trump has been our post-truth president.”

The truth about presidents may now be harder to know. The declining economic health of the news business has weakened its ability to hold presidents accountable. One reason the nation has been in crisis is that journalism is in crisis. Squeezed by financial pressures and disrupted by powerful new technologies, U.S. journalism is struggling to survive. The press will need substantial change if it is to effectively report on government, lessen the polarization that threatens democracy, and combat disinformation that denies election results, climate change, and the existence of pandemics.

Excerpted from Clash: Presidents and the Press in Times of Crisis by Jon Marshall by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2022 by Jon Marshall.