When I was teaching journalism—communication, as most educators prefer nowadays—the authors of a widely used introductory textbook insisted that part of the media’s mission is the "transference of culture." Meaning, perpetuating the mores, habits, etc., good and bad, that bind us as a society. It certainly happens that way, but as a journalist, emphasizing that fact as essentially positive was disturbing to me. I dearly believe that an important part of our function is to hold an open mind on many cultural matters about America, recognizing that it is still a work in progress.

Nevertheless, there it was in the book, being passed on as fact and motto to young, impressionable minds, future journalists who should be taught to raise relevant questions rather than automatically "transfer" culture. Questions about government policy, for instance. Mind you, I am pro-government, a believer in a strong central government—to distinguish myself from right-wing, tear-it-all-down, antigovernment ideologues. I do not want aspiring journalists, and certainly not veteran professionals, to shy away from the extremely tough issues. Like the dicey social issues involving economics,race and racism, gender—problems that divide us but cannot be willed away no matter how we try.

In passing along the traits of our society, the activity of nonprofit organizations by far overshadows that of government. We are bound to and indelibly influenced by churches, school activity such as team sports and cheerleading, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, civic and social clubs, professional groups, PTA councils, college attractions such as fraternities and sororities, foundations and outright propaganda programs such as "support your local police."

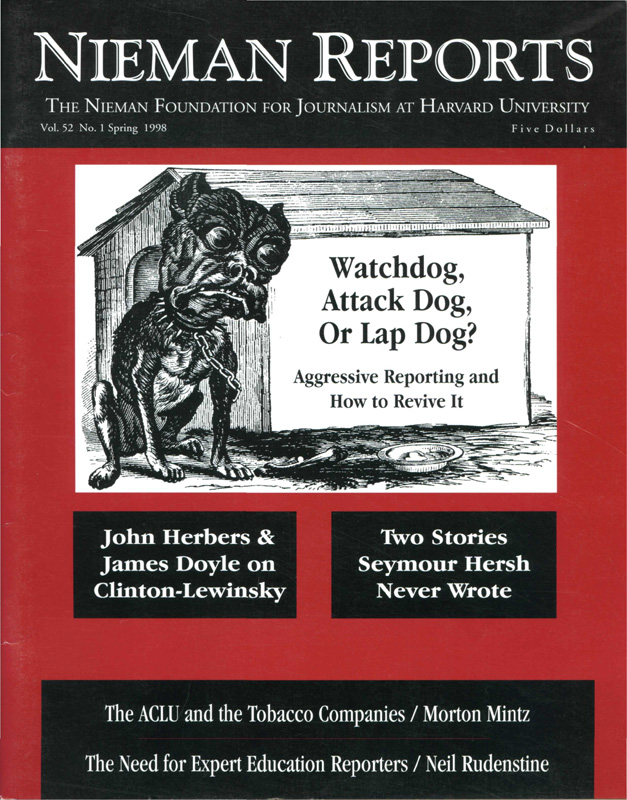

Much of the media coverage of those groups and activities consists of features gloating about the good works the organizations are said to be performing—and let’s agree that most of them perform admirably. However, most of the coverage is superficial, almost propagandistic, as the media put very few resources into delving into the inner-workings of the groups. If one accepts as legitimate and proper the media’s role in transferring culture, they should be much more aggressive as the public’s watchdog in this area.

It is easier, and cheaper, to be passive, and it causes fewer headaches with neighbors and friends, to wink and blink rather than look too closely at possible wrongdoing. The media certainly has a record in the area of social issues, positive and negative. After the civil rights movement of the 1960’s and the great progress made then and subsequently, the government—actually, politicians—was effective in taking the topics off the national agenda. Or at least lowering expectations that the problems could ever be solved, thereby feeding a spreading backlash. Much of the media went along, helping to turn attention away from the unpleasantness that those issues generated.

The inattention was also the result of a number of other factors: our short attention span, our penchant for very short-lived fads, the focus on self during the "me-generation," and the fact that many Americans were just plain tired of being reminded that those serious problems seemed so intractable, tired of hearing about race. Plus, urban, social and racial problems were so complex that it was easy to move on. Editors and reporters did so.

In this atmosphere, therefore, the deficient coverage of nonprofits and philanthropy should be no surprise. At the end of the 20th Century, much of mainstream media is reeling from the same forces that are shaking and shaping our world. Globalism, mergers, the unseemly encroachment of business into areas of our lives that were previously respected as off-limits, the pace and immediacy of events, the ever-changing ethnic makeup of the country and resulting turf fighting, the amount of information and misinformation out there, and most importantly, the powerful impact that information, whether it is true or false, has on people the world over.

In addition, journalists remain pretty distant from the average reader. This is more so today than, say, 100 years ago when the nation was smaller, topics and beats easier to cover and, to a certain extent, rather homogeneous. As immigrants kept coming, and particularly as their hues became darker, conflict was exacerbated, making solutions and coverage much more difficult.

Also, owners and publishers can finally escape the old accusation that they are in the pockets of big business, mainly because now they are big business. As such, they are even more distant from the masses than their employees, the reporters and editors. The shrinking of the field by mergers and gobbling up by non-media moguls and corporations, already generally regarded as very dangerous, was made easier by the encroachment that 1mentioned, whereby we were all softened up by steady propaganda that allowed the corporations to be portrayed as the good guys. They convinced a sizable chunk of the public that business can do it all, that it commits no wrong, can solve all problems, run the schools, operate governments, even nations.

We were softened into accepting that credo, for example, by the corporate gallop to rescue us from the economic mess that they and the politicians helped to get us in. The payback for that rescue is a blank check that permits the logo and motto and brand name into our homes and onto our institutional nameplates: MCI-Capital Arena, Nokia Sugar Bowl, Southwestern Bell Cotton Bowl and even Poulan/Weed Eater Independence Bowl. Where will it end?Will we someday have to contend with the Bell Atlantic-White House? Black and Decker-Yale University? I hesitate making such suggestions even in jest for fear they may come to pass.

Given this recent history and background and trend, why would anyone expect media coverage of nonprofits to be much different from what it has been, or better? Given that mainstream media follow the actions and activities of government—check the number of journalists covering Congress and the Administration—and politicians are not usually in a mood to tackle something as numbing as race, etc., the small part of the nonprofit community that focuses on serious social problems will continue to receive short shrift. Those kinds of stories are not at the top of too many journalists’ priority lists.

"A reporter wishing to make his or her mark at the company is not going to waste time on stories the editors are not going to put on page one or pay much attention to," remarked a foundation official and former journalist.

"Most papers don’t see a great deal to be gained by assigning a nonprofit beat. Or, if they do, they’ll name a weak reporter, or someone on the way out, or someone out of favor the editors don’t know what else to do with— that’s symptomatic of the thinking in the newsroom."

On the other hand, another foundation officer said the nonprofits share some of the blame for the trouble with the media. He said many nonprofits have neither the skills nor resources to communicate their message, in contrast to corporations and some individuals of stature. "Many nonprofits do not have the sophistication to know that’s what they need to do," he commented.

He cited a study of organization leaders who were asked what they were doing to get their story out. Some said they refuse to talk to journalists, not even about good things, "because the press would come back later and look for something bad."

"A lot of local nonprofits feel the press is out to get them, that it is not interested in the positive things they do," he went on. "There is some merit to that. I found journalists much too interested in conflict and negatives."

Unless there is a radical turnaround, the media will maintain their ho-hum attitude, devoting little substantive coverage to nonprofits, and will present more of the same light features and breaking news when there is scandal— remember the United Way and Jim Bakker.

But it is in the mundane area of local government budgets, for example, that media should be concentrating, rather than the nightly trek through police blotters and looking for the wild and weird that compete with the likes of Jenny Jones and Jerry Springer.

Stories like the activity of the president of the National Baptist Convention should be on the front page long before his wife is arrested to provide a peg—again, from the police blotter.

Journalists should be on the case of a William Aramony early rather than late; they should go over corporate and philanthropic boards as they would a presidential appointment. Who’s on local and national boards and what, if any benefits, they receive, as well as the salaries and perks of administrators, are legitimate public concerns that demand press scrutiny.

As for nonprofits themselves, they should open themselves up to closer examination. They need to overcome fear of the media in order to allay the suspicions. The Ford Foundation gives huge sums of money to fund projects in ghettos round the world, but only those privy to organization’s quarterly reports seem to know about a few of the endeavors—not even recipients of the foundation’s generosity. Ford should spend more money on media activity, perhaps setting up shop and establishing an obvious presence in those ghettos and, without employing the unseemly tactics of corporations, let people know the foundation is there—just as media outlets should put bureaus in inner cities if they are serious about quality coverage.

Paul Delaney was a reporter in Washington, Chicago and Madrid for The New York Times. He also served as an editor on The Times National Desk in New York and as a senior editor involved in recruiting reporters and newsroom administration. He gave up his chairmanship of the Department of Journalism at the University of Alabama to help plan for "Our World," a newspaper with a black perspective.

Paul Delaney was a reporter in Washington, Chicago and Madrid for The New York Times. He also served as an editor on The Times National Desk in New York and as a senior editor involved in recruiting reporters and newsroom administration. He gave up his chairmanship of the Department of Journalism at the University of Alabama to help plan for "Our World," a newspaper with a black perspective.