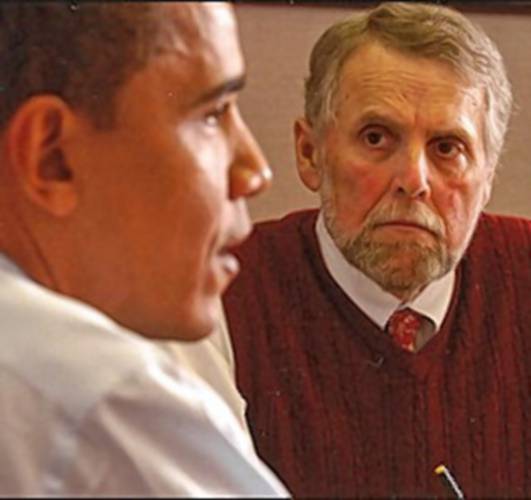

Concord Monitor editor Mike Pride leads an editorial board interview with presidential candidate Barack Obama

Mary Knoblauch, my first full-time editor, died recently. There was a photograph at the wake showing her with a small team of reporters celebrating a series that won some awards. I am one of the reporters in the photo, but the victorious portrait didn’t remotely capture my memory of working for her.

I no longer recall the subject of the story that earned her disapproval and my first professional rebuke, but I won’t forget her beside my desk handing me a typed spelling quiz. I had misspelled several words, including former Chicago Mayor Jane Byrne’s name. She asked that I correct the errors. Most searing was the succinct talk that accompanied the quiz: This is about more than spelling, she told me. You are a good reporter and writer, but you will never be a great journalist if you don’t tend to the details.

Initially I felt humiliated but eventually humbled. I was grateful for the formative lesson at the start of my career and thankful that I came up in an era before hedge fund economics hollowed out newsrooms of mid-level editors like Mary. Many years later, her comments still sting. By habit, I rechecked the spelling of Jane Byrne’s name twice before filing this column.

“Requiem for the Newsroom,” a recent Maureen Dowd column that circulated widely among journalists, mourned the disappearing camaraderie that work-from-home habits and slimmed-down newsrooms have wrought. “I worry that the romance, the alchemy, is gone,” she wrote. I worry too, but about the loss of mentoring, those relationships between the novice and the experienced that are vanishing along with public editors, copy desks, and other editing safeguards once thought fundamental to journalism.

As editing ranks shrink, the stakes rise. Deepfakes and artificial intelligence manipulations pose threats to journalistic credibility that well exceed my spelling errors. The industry needs new protections, including more editors trained in oversight of the emerging technologies.

“As AI tools rapidly get better, pretty much anyone will be able to produce a believable deepfake,” Semafor editor-in-chief Ben Smith wrote. “My own biggest worry is the mischief that will take place where nobody’s watching — in hyperlocal political contests, and in people’s personal lives.”

Not long after Knoblauch’s wake, I traveled to Concord, N.H. for the memorial service of my friend Mike Pride, the Concord Monitor’s legendary editor for a quarter of a century and then administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes. Pride and his paper had won many accolades, including a Nieman Fellowship, the National Press Association’s Editor of the Year award, and the Pulitzer Prize. But his greatest legacy was found there in the pews of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. The journalists who had been mentored by Pride had returned to Concord to pay tribute to their old boss.

Their stories were of a piece. Pride had rolled the dice on them in their 20s, shaped them with editing that was tough but fair, encouraged ambition, watched them graduate to bigger newspapers, then started the cycle over again with a new group of initiates. One eulogist drew knowing laughter from the church when he recalled the withering look Mike gave him for misspelling the word “misspell” in a correction about a misspelling.

By all accounts, that look alone could shape careers. At the memorial that day were Monitor alumni who went on to Pulitzer Prizes and jobs at The Washington Post, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe, National Geographic, and Serial. But it wasn’t always thus. Felice Belman, a former Monitor editor who is now a metro editor at The New York Times, recalled the “boneheaded” mistakes of which they had all been capable when they started in Pride’s newsroom.

“Maybe you were the guy who misspelled Winnipesaukee in a story about Winnipesaukee,” she said. “Or you put too many Us in Sununu. Or too few. Maybe you botched a quote or miscalculated the local tax rate. … Maybe you mixed up Hillsborough and the other Hillsboro. … I know you all made these mistakes — and more —because you told me about them. And with terror in your young voices, you asked: ‘Is Mike going to fire me?’ The answer was almost always no.”

She added, “Small newsrooms in New Hampshire and across the country used to be full of veteran editors — some gifted, some mediocre — who could at least teach the basics to the next generation. But what Mike did for us, and by extension for Concord and for the state, was something quite beyond the basics.”

A week or so after Pride’s memorial service, I watched an episode of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel where the Tony Shalhoub character, writing for the Village Voice, describes himself as suffering a “dark night of the soul” because he misspelled Carol Channing in his column.

“Look at it!” he says, pointing to the paper’s correction before reading it aloud. “‘On Monday, Carol Channing was incorrectly spelled as Chaning.’ Ugh. I’ve been branded. I’m … I’m Hester Prynne! Two Ns in Prynne, by the way.”

The bit was played for comic neurosis and Shalhoub as obsessive, a reminder that the detailed and fastidious are often painted as weird. But I think he would have been Pride’s kind of reporter. As someone taught me, and as Mike well knew, it was always about more than spelling.