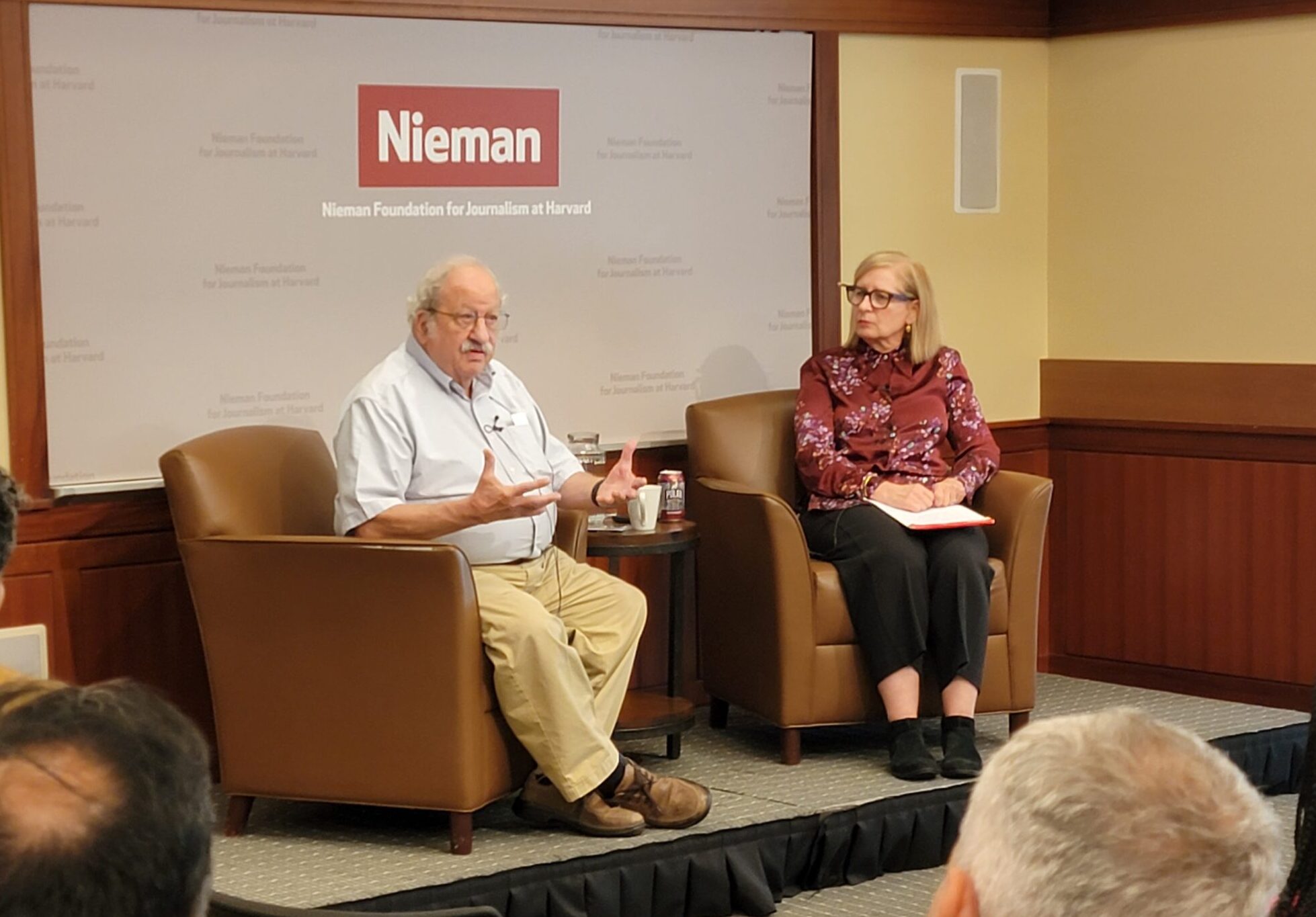

Harvard Kennedy School Marshall Ganz (left) and Nieman Foundation curator Ann Marie Lipinski spoke in conversation with Nieman Fellows in September

Marshall Ganz has a storied history in community organizing. After matriculating to Harvard College in 1960, he left after his junior year to volunteer with the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project and then later joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee as an organizer. In 1965, he began working with Cesar Chavez, and over the course of 16 years with the United Farm Workers, he served as its director of organizing and on its national executive board. In the 1980s, Ganz worked with grassroots organizations to advance voter mobilization initiatives. And during the 2008 presidential election, he played a critical role in designing Barack Obama’s grassroots campaign. Undergirding his multi-decades-work in community organizing is the power of narrative. “By the time I came out of the farmworkers, I knew that you had to have a story,” he told Nieman Fellows in September.

The Rita E. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society at the Harvard Kennedy School, Ganz finished his undergraduate studies in 1992 after a 28-year leave of absence and went on to receive a master’s in public administration and doctorate in sociology from Harvard. Ganz has published work in the American Journal of Sociology, American Political Science Review, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, and more. His books include “Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement,” “¡Sí se puede!: Estrategias para organizarse y cambiar el mundo,” and the forthcoming “People, Power, Change: Organizing for Democratic Renewal.”

Ganz spoke to Nieman Fellows about how to practice leadership, why telling your own story matters, and the power of storytelling for social change. Edited excerpts:

On narrative’s role in social movements

In the civil rights movement, storytelling was so in the fabric of the movement. In other words, you can’t understand a movement like that purely in terms of strategic analysis because heart matters a whole lot in social movements. In that movement, the whole narrative [was] rooted in the Black church, rooted in the story of would-be American democracy — the narrative was incredibly powerful.

It was also linking personal transformation with community transformation with political transformation. In other words, as people were discovering within themselves, their voices, and in each other ways to have a collective voice, at the same time, they were building the power they needed to change the laws — the institutions that were responsible for the problem in the first place. That’s what really hooked me on organizing because of the way to link those three together rather than the kind of separation that they often have.

With the farm workers movement, that was also rooted really in the Mexican Catholic tradition. That dynamic — Mexican cultural history, the myth of the revolution, and the Catholic context — was also very powerful. That’s all storytelling. I mean, that’s what happens in church, synagogue, mosque: storytelling. It was that same linkage of individual, collective, and institution that we were doing.

By the time I came out of the farmworkers [movement], I knew that you had to have a story. The way we put it [was] a story, a strategy, and structure: You had to have a story to explain why. You had to have a strategy to address how. And you had to have a structure to make clear how we were organizing ourselves to actually implement strategy and enact the story.

On leadership as a practice

We’re used to thinking of leadership in terms of positions [of] authority. Authority and leadership are not the same thing. We think, “I am leading based on my authority, which means I essentially give orders.” It can be, but it’s about the exercise of authority. Now, how we construct authority in any organization or movement is a really important question, but we tend to think of leadership in positions.

What I’m suggesting is leadership is better thought of as a practice, as a way of doing things, not something you are. If you think of it that way, it opens things up a lot.

We all know about people who occupy positions of formal leadership who turn out to be awful leaders. We don’t have to look too far for those examples.

On the other hand, it’s been my experience that in communities, and neighborhoods, and workplaces, you meet people who are exercising, practicing leadership in the way I’m describing it, but without the titles and all the rest of it.

By thinking of it in terms of a practice, the question is, “Do you choose to accept responsibility for the practice of leadership?” Which, if you’re operating in this understanding of leadership, then it means enabling others, working with others.

Jo Freeman, [the] feminist sociologist, wrote in 1972 this classic piece called “The Tyranny of Structurelessness.” What she argues is that when you don’t have a formal structure for decision-making and all the rest, people are still going to form a structure. It just won’t be visible. It won’t be transparent. It won’t be accessible. Pretty soon, it’ll be like, “Well, who decided that?” Then all the factions grow.

It’s a way to actually accept responsibility for creating and working with others to create the mechanisms, including structure, that can create the space in which to actually do this kind of work. In other words, I’ve come to think the opposite of structure is not space. The opposite of structure is chaos. It takes structure to create space.

On using your own personal story

When your profession is telling other people’s stories, what about your own story? Well, that’s challenging. I think it’s critically important because you’re telling other people’s stories, but not from nowhere.

We all have perspectives. We have life experiences. We have values that attract us to the stories we want to tell. For me, it’s been a useful exercise to get clearer about what one’s own motivations are. There’s a way in which things can be influences on us, that can become resources for us, including the sources of our own motivation and the sources of our own caring. That’s what we get at with the story of self-work.

The more we teach this stuff, we discover how fundamental it is to struggle with articulation of, “Why [do] you care what you care for? Why are you doing what you’re doing?” Because the reality is that most of us have had hurt experiences in which we learned to care. If we hadn’t had those experiences, we wouldn’t think the world needed fixing. Also, we have experiences of our worth and our value, or else we wouldn’t be here trying to change it.

Right now, in our online class on public narrative, we have about 130 students from about 30 countries, and [we’re] working together to find the courage to actually share. To allow yourself to be seen so that you can see others is very powerful.

On the downfalls of political messaging

We have this political marketing industry in the United States unlike any place else because we have no constraints on campaign spending.

We’ve created this multi-billion-dollar industry that’s essentially an advertising industry that takes the place of political discourse with marketing. Messaging is so different from political communication, discourse, conversation, narrative, and all the rest. It’s just this unilateral thing that you send out there.

I think a lot of progressive movements have been trapped into that messaging deal and forgetting the fact that the ground is people, and it’s how people engage with other people. [Social media] been so disabling. It creates the illusion that, “Oh, you’re talking to the whole world because you can count the number of likes or whatever,” but it’s an illusion.

On leaders

Charismatic leadership has been around for a long time. Every faith tradition starts with charismatic leadership of some form. What they’re doing is challenging the existing framework of value and power. You see Jesus doing that. You see the Prophet doing that. There’s this existing wealth and power and you’re trying to say, “Hey, here’s this other deal over here. Leave that and join this.”

Now, what is it that enables people to find the courage to do that, or the meaning to do it? Some people are very good at it, but it’s a problem that the charisma gets projected on them in a way.

One of the values of the Selma movie, I thought, was that it showed that Dr. King was not a solo performer. There were all kinds of people involved. It was much more of a collective, but then, who gets baptized to be the spokesperson?

That also often creates a lot of problems within the movement because they’ll say, “Well hey, the press decided so and so, but we didn’t choose that person.”

Today it’s really bad because you can become a celebrity because some philanthropist thinks you should be and not because you built a constituency that has chosen you to be their spokesperson.

I think sitting around and waiting for the savior is not such a good proposition. Movements that are much more conscious about that and that are trying to enable more voices to be heard than just one, that’s a strength of the movement.

People are trying to say, “No, it’s a leaderless movement.” Well, that’s not true. It’s no such thing. It’s not helpful because then nobody’s voices get heard, or the voice that gets heard is the one who sees it as an opportunity to make their voice heard, and that may not be the person that you want the voice heard by.