There’s plenty I don’t remember about my first presidential campaign. I was in the sixth grade, after all, joining my dad, Richard Harwood, a 1956 Nieman Fellow, as he covered the race for The Washington Post. The year was 1968. What I do remember, and what I’ve learned as I followed my father into this sometimes-exhilarating and sometimes-dispiriting business, provides a window through which to see how much has changed about political journalism. And how much hasn’t.

Start with the relationship between the candidates and the reporters who cover them. It was deeper and more honest then. My dad, who barely knew Bobby Kennedy at the start of his 1968 primary campaign, had become close to him by the time Kennedy was assassinated—so close that he asked the Post to take him off the campaign because he felt he could no longer be objective. Back then, reporter and politician spent a lot of time together in unguarded settings, which were both on- and off-the-record.

In the hothouse atmosphere of today’s campaign, reporters and candidates spend much less time together. And the time we do spend is mediated much more heavily by the armies of communication strategists that each campaign employs to guard against verbal missteps. Considering the ubiquity and speed of correspondents filing for the wires, the Web, and for cable TV, not to mention newspapers, campaigns have good reason to be so cautious. The result is that I don’t know any of the 2004 candidates as well as my dad knew Bobby Kennedy.

Prevailing rules of journalistic ethics would say that’s a good thing. In 1968, I appeared in Kennedy’s TV ads after my politically active mother volunteered me to join a group of kids in a filmed roundtable discussion with Kennedy. Dad had nothing to do with this, but the ads ran in contested primaries that he was covering. If it came to light today that my daughter was appearing in ads for Howard Dean or George Bush, other reporters would cover it as a minor scandal, which is why it wouldn’t happen.

Does this heightened ethical sensibility produce a truer report for readers, listeners and viewers? Maybe, but maybe not. The reports my dad filed almost invariably contained news of first impression for his editors and the vast majority of his readers. When he took me once to a dreadfully hot state fair to hear George McGovern, standing in for the fallen Kennedy, his technological equipment was limited to a portable typewriter; he could dictate, if he could find a phone, or file to the Post from a Western Union office. Those techniques of transmitting news were glacial by today’s standards, but they contained a crucial element that is harder to come by today: Facts were the news, and the news was fresh.

Stories that I file from the 2004 campaign trail usually do not contain news of first impression—for editors or for readers. This is because of changes in technology and the media business. Nearly anything important that a candidate says today is covered live by CNN or MSNBC or another cable outlet. In fact, I might well have discussed whatever I am writing about on television even before I start writing; The Wall Street Journal, like other newspapers looking to stem readership declines by building brand identity, sends people like me in front of television cameras more often than my dad could ever have imagined. Sometimes I do a half-dozen “talking-head” appearances in a day.

As a result, stories I write must command the attention of readers less by the news they contain than by the analysis they offer. That introduces the possibility of a far different sort of bias than coziness with a candidate; it is the bias of analysis in my idiosyncratic conception of what are the most relevant and important trends I see in the campaign and the country. Which reportorial bias is more pernicious? It’s a tough question to answer.

While we are less familiar with candidates, we are more familiar with the legion of media consultants, pollsters and strategists who are the mercenary soldiers of the permanent campaign. In my dad’s day a candidate’s innermost corps of advisers usually consisted of longtime, loyal aides from the candidate’s home city or state; today these advisors are hired strategists who are as much of a fixture within the Beltway culture as the lobbyists swarming Capitol Hill. Within a few weeks in 2003, one communications strategist had left Senator John Kerry’s campaign and gone to work for his rival General Wesley Clark. If there’s a coziness problem in political journalism today, it is the coziness among reporters and these political consultants, who often have agendas distinct from those of the candidates they briefly serve.

The culture of the campaign press corps has changed as much as the culture of campaigns themselves. That’s largely because of the women’s movement. With some exceptions like the great Mary McGrory, the campaign planes, buses and trains of my dad’s generation were almost entirely male domains. That’s no longer true. Changing gender roles also mean the male reporters are much less inclined to stay out on the long, guilt-free trips that my dad used to take. A colleague yearning for the good old days of long, whiskey-soaked road trips once wrote a piece making fun of me for leaving George Bush’s campaign plane to go home for Halloween trick-or-treating with my children. But I’m far from the only one making such detours home. And while on the road, reporters of my generation spend a lot more time working out than drinking whiskey.

Evolving technology means that even when we are away from the candidates, we are never truly away from the campaign. When my father traveled—long before anyone dreamed of cell phones—campaign reporters were incommunicado for long stretches, and when they left the campaign, they were disconnected from being able to report on it. Today, C-SPAN brings campaign events into one’s living room, and communications with campaign strategists continue apace with blizzards of campaign e-mail messages appearing at all hours of the day and night. The constant buzz of a vibrating BlackBerry, the ascendant vehicle for e-mail interviews and campaign attacks alike, has become a hated sound for family members of political journalists who rarely leave home without these wireless devices. At night, they put them next to their bed.

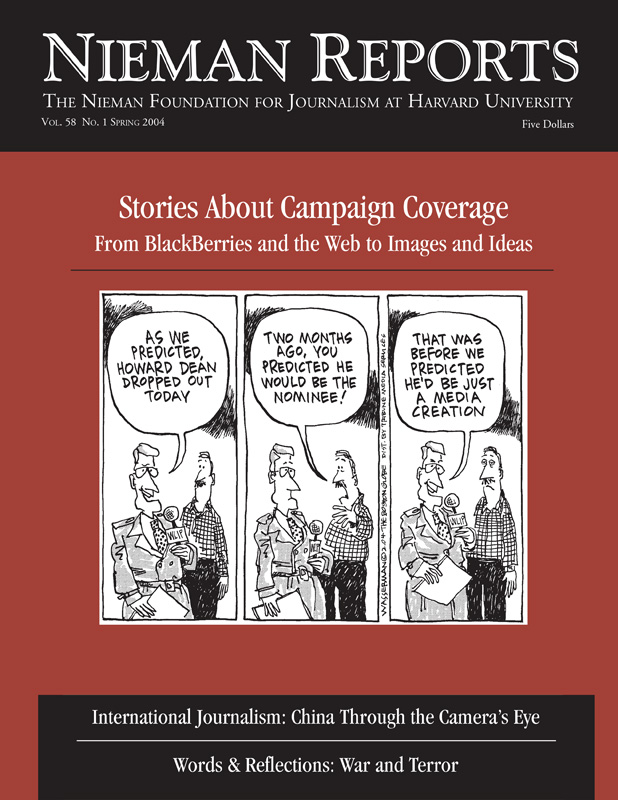

Some media observers complain that political punditry now plays an outsized role in the election process, lifting favored candidates and burying disfavored ones long before ordinary voters are paying the slightest attention. But this is where things haven’t changed all that much. The dominant media paradigm—before the Iowa caucuses or New Hampshire primary were the focus of much attention—was that former Vermont Governor Howard Dean had seized control of the Democratic nomination race. Yet in the first election test in Iowa, Kerry’s convincing victory and Senator John Edwards’s strong second-place finish proved that the voters have minds of their own, just as they did in 1968 in pressuring President Lyndon Johnson out of the race for his party’s nomination.

What this tells us is that political reporters like me need to constantly be willing to question our assumptions and revisit the analytical frameworks that we use to predict the future. I have access to so many more polls than my dad ever did, and they offer me and other reporters snapshots of how and what voters are thinking about the election that lies ahead. But what voters decide can erase any of those snapshots as easily as I can delete a digital image from my laptop computer. That’s still the good news—the exciting news—about the craft of political journalism that I am fortunate enough to practice.

John Harwood, a 1990 Nieman Fellow, is the political editor of The Wall Street Journal. Based in Washington, he is covering the 2004 presidential campaign for the newspaper.