Can journalism survive in this era of punditry and attitude? If so, how?

Nieman Reports posed this question about journalism’s future to 15 journalists who work in radio and television, at newspapers or with Weblogs, or who teach the next generation of reporters, editors, producers and bloggers. The assignment: Reflect on the question and write an 800-word essay that emerges out of relevant experiences lived or observed.

Surveys of journalists—such as one conducted in May by Pew Research Center and the Project for Excellence in Journalism—are finding echoes of the increasingly critical assessments that members of the public have been giving about news reporting for many years. A large majority of the 547 national and local journalists interviewed believe that profit pressures are seriously hurting news coverage. Nearly half of national journalists say the press is too timid in its reporting, and nearly two-thirds of all the journalists think there are too many cable talk shows on TV. The report cites a “crisis of confidence,” and Pew’s director, Andrew Kohut, said of the survey’s findings: “The press is an unhappy lot. They don’t feel good about our profession in many ways.”

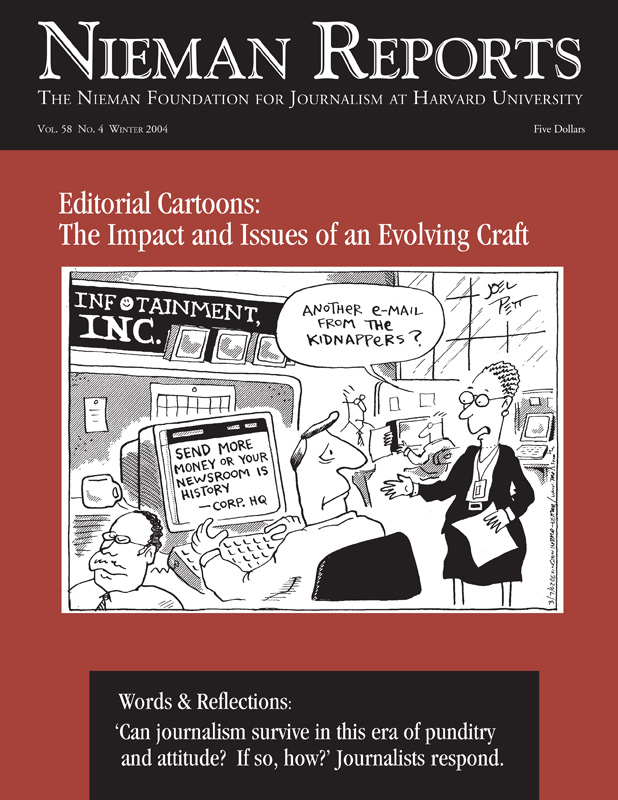

News coverage is becoming increasingly fragmented. At the same time, journalists find themselves confronting the pressures of economic constraints (with fewer resources being devoted to reporting) and the push toward entertainment (with stories of dubious news value trumping those of arguably more importance). In this climate, Nieman Reports decided to depart from its customary examination of coverage of a specific topic and widen our scope to look at the prospects for journalism’s future given where things stand today.

Books

Doug Struck, who since 1990 has reported often from Iraq and the Middle East for The Washington Post, uses the book, “Al-Jazeera: The Story of the Network That is Rattling Governments and Redefining Modern Journalism,” as a point of departure as he writes about what it is like for Arab and U.S. journalists to report on the war in Iraq—and how the content of what they report and broadcast often intersect. “The squeamish secret among Western journalists in Baghdad is that these [Arab] stations are now an important part of their establishment news operations,” he writes.

Susana Barciela, a member of The Miami Herald’s editorial board, describes “American Gulag: Inside U.S. Immigration Prisons,” as an “exposé of institutional cruelty” that “is a must-read for journalists covering immigration or living in immigrant-rich communities.” She observes how the author, Mark Dow, has “meticulously researched” this topic, and his “abundance of facts,” she writes, proves “that the lack of transparency and oversight has resulted in the systemic abuse of immigrants locked up from Seattle to Key West.”

Mauricio Lloreda, an op-ed columnist for El Tiempo in Colombia, finds in June Carolyn Erlick’s book, “Disappeared: A Journalist Silenced: The Irma Flaquer Story,” that events from the past “can offer us much to contemplate about our present.” As Lloreda writes, “Erlick’s portrayal of this Latin American journalist’s life and death speaks to what has happened—and continues to happen—under similar circumstances in countries throughout the world and particularly in this region.”