Last summer I returned to a subject I have reported on many times before — why families don’t have health insurance and the consequences that result. This time I looked in-depth at what was happening in Tennessee, where some 200,000 people, mostly poor, were being cut off from TennCare, the state’s bold expanded Medicaid program established a decade ago. For more than 10 years when these people had insurance coverage, they received better medical care and with it came better health.The state paid the bill, but when the cost became too expensive for Tennessee’s political leaders to support, the Democratic Governor Phil Bredesen decided to trim the rolls of this program, and his staff carefully crafted a plan that cut these families and individuals adrift.

As I listened to those who no longer had health insurance, their stories were wrenching. One woman told me she was lucky to have breast cancer because that meant she could stay on TennCare. Even so, the state’s new limits on prescription drug coverage forced her to choose which of three other life-threatening diseases she would treat. There was another woman who told me about a mole growing near her eye. She said that no doctor would remove it because she lacked insurance and did not have the money to pay for surgery. A health department physician in her county told her to come back in three months; he would take another photo to see what kind of treatment she needed if, by then, she could pay for it.

No woman with health insurance would utter the word "fortunate" to describe what it is like having breast cancer. Nor would anyone wait for a potentially cancerous growth to grow larger before having it removed, if they had a choice.

Middle Class vs. the Poor

Consider the public outrage against health maintenance organizations (HMO’s) in the 1990’s when, in an effort to control costs, patients often had to wait to be seen by specialists. Remember the outcry when HMO’s refused to pay for extra hospital days after a normal delivery, which their mostly middle-class moms wanted for rest. Political leaders couldn’t vote fast enough to mandate that HMO’s pay for three-day stays, even though for most women this length of stay is medically unnecessary. These mandates forced HMO’s to spend money on wasted care at the expense of more pressing needs, such as programs to improve nutrition for their elderly members who are often poorly nourished.

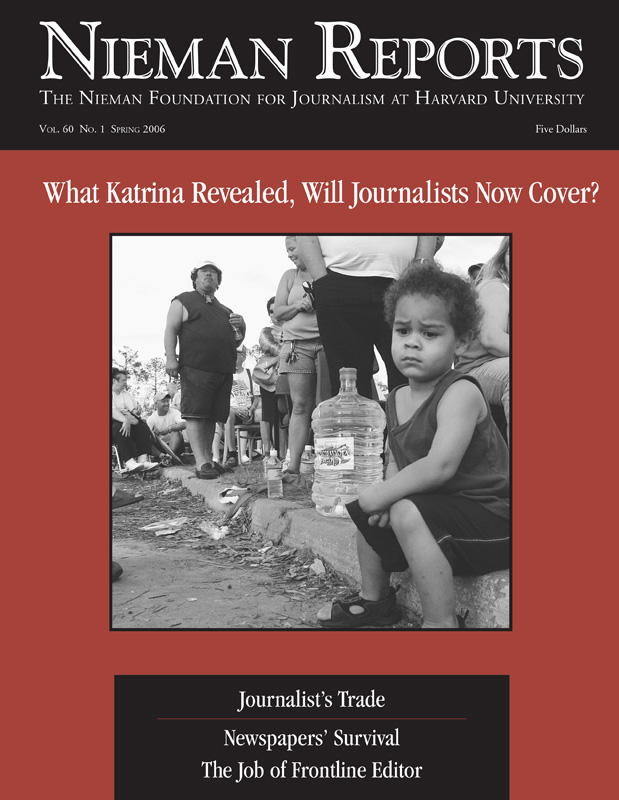

The stark truth is that health policies and practices in the United States ration health care. The TennCare experience displayed this as poignantly, if not as vividly, as did the bodies of poor people floating in the post-Katrina streets of New Orleans. Of course, medical systems in all countries limit health care in some ways; in this country, though perhaps it goes unspoken, the policy choice has been to limit the medical care available to those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder. They are less visible politically. They don’t raise much of a ruckus, don’t have a lot of well-paid lobbyists to plead their case, and they usually don’t vote, all of which makes them expendable in the political calculus.

Last summer, however, in Tennessee advocates for those dropped from the TennCare rolls raised a ruckus, or at least they tried to. Every night from late June until Labor Day they held a candlelight vigil at the state capitol in Nashville, and every day they congregated on the capitol steps to raise awareness of the inevitable — the deterioration in health and well-being that results when no money is available to pay for care. They convened town meetings and gathered signatures from state lawmakers for a special legislative session. They asked for a public meeting with the governor. Despite their efforts, the governor and the politicians he controls were unmoved. The governor did call a special session, but that was to consider government ethics, not the TennCare cuts.

Ignoring the Real Story

Three weeks into the protests, the Nashville television station, WTVF, broadcast a story lamenting that because of the sit-in — and the extra state troopers required to police it — every hour of the protest was costing taxpayers money. Then, around Thanksgiving, the city’s alternative newspaper, Nashville Scene, published a story about Tennesseans who had lost their health care coverage, some of whom had died. But the writer, John Spragens, concluded his article with these words:

"Who is to say whether Bredesen’s TennCare reforms are the tough medicine this state must swallow — whether, as he said last week, ‘we’re getting the results we need?’ Perhaps this is, as he insists, the best of some bad options. Who knows?"

Reading this made me wonder how the public is supposed to "know" when the news media is unwilling — or unable — to present them with the necessary information. Like other stories about the plight of the uninsured, this article did not tackle the difficult subject of rationing, nor did it explore alternative proposals to keep people insured.

Perhaps one reason the writer hesitated to take the reader there was that the state’s political leaders refused to discuss these other dimensions, either. The steadfast posture, held by state officials, was that Tennessee could not afford the cost. As someone coming from outside the state — and trying to understand the dynamics of what was happening — I wondered whether members of the local press should be taking politicians to task for failing to address such issues.

Drew Altman, the thoughtful head of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which serves as a resource for journalists, contends that we — politicians, journalists and the public — have yet to confront health care’s core issue. "It is a problem of reallocating wealth in America," Altman says, "and we don’t do that very well." Indeed the news media avoid the subject, as well as most other topics connected with the nation’s health care have-nots.

Such stories make readers, listeners and viewers uncomfortable by reminding them of how vulnerable all of us are. Nor do such stories fit into today’s paradigm of health news. Editors prefer personal health stories, the kind with exercise and diet tips or ones that hype a yet-to-be-proven treatment to head off Alzheimer’s disease. This is market-driven journalism fueled by advertising dollars for pharmaceuticals, new technology and health care services, and by focus groups, which supposedly reveal that readers want to know how to lose weight or where to buy pills that will make them healthier.

A young reporter, who is well-trained in health journalism and works at a Wisconsin newspaper, told me that she cannot interest her editors in stories about health care inequalities or other health policy issues. "Let’s just say they aren’t intrigued," is how she put it. Someone who works on the business side of a national publication explains that when there are too many stories in her magazine about Medicare or health insurance the concern is that reporters might wander into the forbidden territory of universal coverage, and this might offend readers.

Altman notes that the number of reporters who call him has decreased during the past 10 or 15 years. He attributes this decline to changes in the news business. Occasionally there is a major story about the uninsured or a report about a study in which blacks were found to receive worse medical care for heart attacks than whites. But those stories are scarce and, like the story about TennCare in the Nashville Scene, these articles rarely delve into potential solutions that might lead to improvement. It’s as if quiet censorship envelops the topic.

Gaps in Health Care Coverage

The dilemma of reporting on the gaps in health care brings up the age-old question in journalism: Does the press follow what newsmakers do or does it lead, based on what its reporting determines are problems? At this time, I’d argue the news media are following, as they chase after advertising dollars and a bigger audience. Focus groups help to shape coverage, too, as consumers tell publishing executives what they want, and it rarely includes a desire for more news about the ever-widening gap between the health care haves and have-nots.

This is happening at a time when the backbone of the American health insurance system — employer-based health care coverage — weakens as more companies eliminate or reduce health benefits for employees and retirees. With government and companies less inclined to regard this as "their problem," the imperative for editorial leadership in tackling this subject is greater than ever.

A poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, conducted in October 2005, shows that the public is more worried about having to pay more money for health care or health insurance than many other family concerns. The 1,200 adults polled were almost twice as worried about paying for health insurance or health care (40 percent) as they were about paying their rent or a mortgage (22 percent). They were nearly three times as concerned about health matters as about losing savings in the stock market (14 percent). When compared with the worry they expressed about being a victim of a terrorist attack (18 percent), health issues were again of much greater concern.

Public concern about health care appears to be nearly as high as it was in the early 1990’s when Harris Wofford ran for the U.S. Senate in Pennsylvania and his victory — based in large measure on the power of this issue — sparked a national debate on health care reform early in Bill Clinton’s presidency. Yet for some reason that level of concern has failed to translate into political change.

What role, if any, do the news media play in maintaining this disconnect between what people indicate they want from their political leaders and actual changes in policy?

Not long ago I was wandering through the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C. and came across his remarks carved into the granite: "The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much, it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little."

In reading those words, I thought about those in Tennessee whose circumstances I’d covered and of those in other states in similar situations whose stories too often go untold. I thought, too, about the kinds of stories that are told for and about upscale audiences, whose daily lives and well-being are not challenged by the decisions of government policymakers. We don’t have much sense of social welfare in this country — not much sense of the common good, and our media coverage reflects that.

Earlier this winter, FDR’s point hit home again when a beggar appeared in a New York subway car. "I’m hungry," he said, "Can someone help me eat?" He was skinny as a rail, his suit coat hung loosely on his shrunken frame, and his eyes were sunken. Most likely he was sick as well as hungry. I gave him a clementine; a man at the end of the car stood up and offered a banana; a young girl next to me thrust a couple of dollar bills into his hand. At that moment, too, I thought of FDR’s injunction and of my profession. I found it wanting.

Trudy Lieberman is director of the Center for Consumer Health Choices at Consumers Union, a contributing editor to the Columbia Journalism Review, and president of the Association of Health Care Journalists. She is writing a book about health care in America to be published by the University of California Press.