On December 5th, the 17-year-old son of Salinas, California Councilwoman Gloria de la Rosa, a well-regarded member of the community, was shot in the back after a street altercation. In a city gripped by gang violence, where drive-by shootings are almost routine, a kid who survives an attempt on his life seldom merits more than a breaking police story. Except in this case he was the son of a prominent politician, a woman who has spoken out against gang violence for years.

I drove to her home for a follow-up story, where I met two women who are representative of this working-class city in California’s central coast: Latinas, middle-aged, mothers of young children. Luz is a farm worker who resumes her involvement in the community in the winter, once her work in the fields dwindles. Rosa works for a nonprofit aimed at curbing gang violence. The women recognized me and smiled. It was a shame, they told me, that something like this happened to Gloria, one of the most active council members. "Nobody else is out there doing anything," Rosa went on to say, but then she cautioned. "But don’t put that in the paper." (In my newspaper’s coverage of this story, these women’s names were changed at their request, due to their stated reluctance to be quoted in their discussions about race.)

"Yeah," Luz chimed in. "Don’t put this in the paper either, but I’m going to tell you something. The police, they don’t care if Hispanics kill each other. All they do is go round up brown kids, put them in jail, but that doesn’t stop the killings. If white people started getting shot, the police would do something about it. But you’re not going to put that in the paper, are you?"

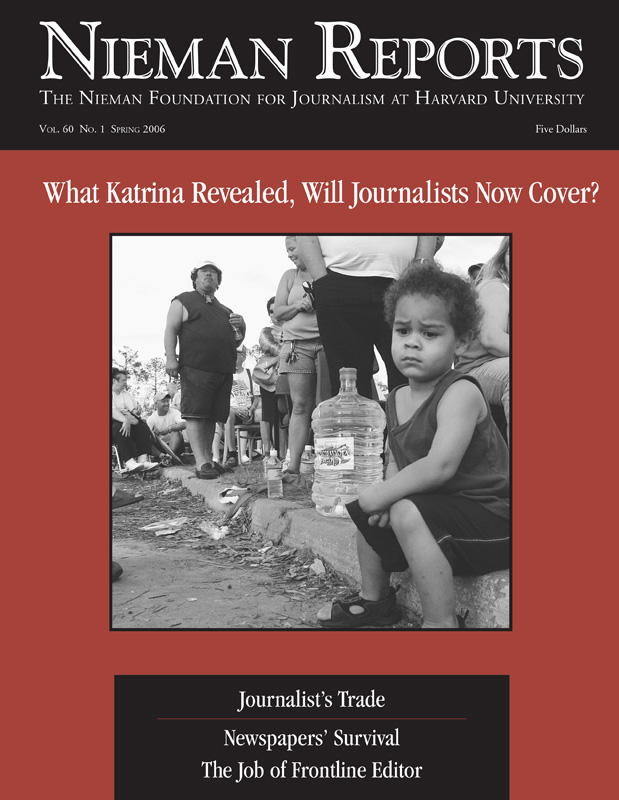

Just like the people in New Orleans after Katrina, who felt it was their race that had trapped them in the Superdome for days with no food and no water, people in Salinas often feel that their everyday struggles somehow have something to do with their background. They feel that if they get fired from a job it’s because they’re Hispanic, that if their children get picked up by the police it’s because of the color of their skin, and if the police appear to do nothing to stem gang violence it’s because it’s only brown people who are dying.

Journalists and the Latino Story

They almost always feel, too, that the news media are not doing a good job at covering what happens in Latino communities. As a reporter for one of the city’s daily newspaper, The Monterey County Herald, I am a part of what they like to point a finger at. Even though I struggle every day with attempting to paint a more complex view into the Latino community, I face obstacles — some institutional, some personal — that stand like an invisible line between covering race and covering it up. Some people don’t like talking about race and racism, so they unwillingly contribute to the silence on racial matters. Some topics involved with race are so complex that it is hard to report and write about them on a regular basis. Sometimes I can’t figure out how to incorporate race and ethnicity in a story, so I try to sneak it in or I decide to leave it out.

The truth is that gang violence in the Central Coast region of California is the result of complicated, long standing relationships developed among "prison gangs" and "street gangs" to control the drug trade. Latino children, often home alone as both parents work in the fields, are easy prey for older gang members, who have often served time in prison and now want to recruit new "soldiers" to join their cause. It is in this way that the Central Coast’s lucrative agricultural industry becomes the perfect breeding ground for street gangs. And the majority of the members of these gangs are Latino children, since it is their Mexican migrant parents who work in the fields.

Much the same can be said for almost all of the social ills in Monterey County. Its economy is fueled by the low-paying agricultural jobs and service-industry jobs related to tourism, and these jobs don’t pay enough for low-wage workers to have decent housing or health care, and the schools their children attend are resource-poor as well. Those who live at the bottom of the region’s socioeconomic ladder, Latinos, are the ones who feel the brunt of these problems. Many of the workers are unskilled, and they lack a formal education, and it can be difficult for them to understand the economic formulas that have placed whites atop and people of color at the bottom. All they know is that they feel it’s not right that their children don’t receive a good education, or that they live in dilapidated housing, or that they can’t afford health insurance.

The Dilemma of Race

Because they don’t have a name to capture what they feel, they call it racism. But when they talk with me or other reporters about their lives and about these issues, they refuse to be quoted. And this presents me with a dilemma: How do I report on these complicated and historic formulas of white privilege and the disadvantage of color in a 12-inch story and on deadline? How do I convince my sources, whether it’s a woman I speak with on the street or a county supervisor, to tell me on the record that they believe there’s a racist tinge on how these things play out in their daily lives?

After witnessing thousands of black people trapped not just by Katrina’s devastating effects but also by their poverty and its evident intersection with race, there’s been a lot of hand-wringing by journalists about how to do a better job covering race — and the divisive social issues that are a part of this story. Even if we know that the direct cause is racism, the overt discrimination of people based on the color of their skin, nobody seems to know what to call what they see, either. Even worse, for us, we don’t know how to incorporate these important dimensions into our daily coverage, or how to come up with in-depth pieces that could help people to look at these issues more thoughtfully.

In my daily coverage of Salinas and surrounding areas, I often try to incorporate tidbits of information that would give a fuller picture of people’s ethnic, social and economic background. For instance, in stories about parents volunteering at their children’s schools, I mention the Mexican state where they come from; or at social gatherings I describe the music they hear (mariachi or ranchera) or food (tamales and champurrado).

At times I’ve found that editors are cautious when it comes to stories that mention race or ethnicity. I was assigned, for example, to write a story about an elderly white woman who collects Nativity scenes. In my story, I mentioned how ironic it was that this woman lamented the decline of this Christian custom while just driving around Salinas would show anyone that Latino families are keeping this tradition alive and healthy. Making this point in that article was perhaps my timid attempt to remind readers that Salinas is 67 percent Latino, and many of them are people who keep their strong Catholic traditions and allow these religious scenes to be visible while many white families no longer do because of cultural messages about such public display. But with this story, the word "Latino" didn’t make it into the paper.

When I worked in Latino news media, whether my stories were written in English or Spanish, writing about race and class — without having to explain myself to the higher ups at the paper — was routine. The editors there knew, as the audience did, that this country’s history has been built on the backs of people of color and that hundreds of years of discrimination are not erased with a couple of decades of good intentions. Ethnic media, which historically has been more crusading than its mainstream peers, does not flinch at telling lopsided stories about injustice in which the writer is seen as favoring those who are being wronged.

Isn’t that what journalism is supposed to be about, to comfort the afflicted?

Mainstream news media are different. These news outlets feel straightjacketed by the artificial demands of "objectivity" and "balance," in which the attempt is often made to quote equally from those on both sides of an argument. With this formula, what we end up with are stories of "he said, she said" that give little depth to the real issues. These kinds of stories fail to convey to our readers the frustration or the drama when a Latino working mother sees her child in jail — or learns that he has died — then holds in her heart the sense that her family has been dealt an unfair hand. Nor do these stories share with readers her inability to explain why.

What makes this extremely difficult for reporters is that when it comes to talking frankly about issues of inequality and ethnicity, few people are willing to open up. People who have suffered discrimination are afraid to run into trouble with the police, teachers or elected officials. They’re wary of the backlash, afraid of what their white neighbors might say if they are seen as calling them racists in a public forum. Racism is not a pretty word, and they know deep down that perhaps racism is not quite the right term. But they don’t have another word to use and, without us being able to establish a dialogue about this as part of our news reporting, it might take us quite a while to find one.

Claudia Meléndez Salinas is a staff writer at the Salinas bureau of The Monterey County Herald. An immigrant from Mexico, she has written about the Latino community for more than a decade at publications such as El Andar magazine, Nuevo Mundo, the San Jose Mercury News, and Mexico’s La Jornada. She is a current fellow at the Institute for Justice in Journalism at USC Annenberg School for Communications.