Members of Argentina’s "Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo" in San Martin Square, opposite Argentina’s foreign ministry. November 1977. Photo courtesy of The Associated Press.

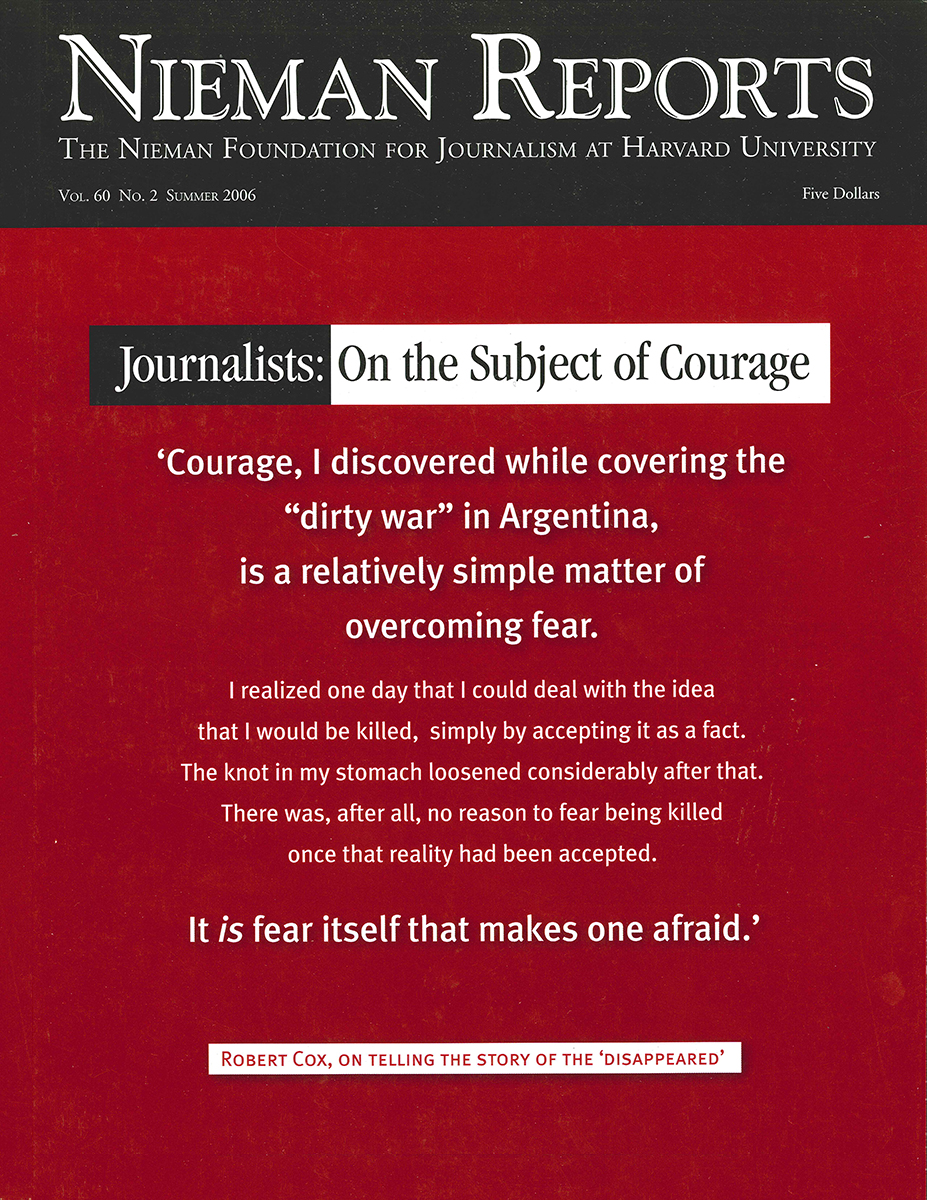

Courage, I discovered while covering the "dirty war" in Argentina, is a relatively simple matter of overcoming fear. I realized one day that I could deal with the idea that I would be killed, simply by accepting it as a fact. The knot in my stomach loosened considerably after that. There was, after all, no reason to fear being killed once that reality had been accepted. It is fear itself that makes one afraid.

I thought this approach was a pretty good ruse because it allowed me to behave quite normally. So much so, that I have told friends who are fearful of flying that they will have no difficulty in getting on board the plane if they have already made up their mind that the plane will crash and they will die, though nobody to whom I have told my theory for overcoming fear of flying has told me that they have tried it, and it works. But by facing every day in Argentina expecting to be murdered, telling myself that this was exactly how it was going to be, worked for me.

I feel a striking identification with Iraqi journalists who are covering most of the war from outside well-fortified, protected zones after it has become too dangerous for the easily recognizable foreign correspondents to get out and about, even in Baghdad. Some Iraqi reporters explain that their ability to function is because they accept their inevitable date with death. Acceptance is the secret; it is a kind of grace.

Naturally, there was a bit more to it than that. I also decided I would do as much as I could to avoid being killed. That meant I needed to make plans to avoid being captured. At the same time, I told myself I must maintain absolute normalcy. I continued to take the "colectivo" (bus) to work, but tried to avoid being alone on the street. I remember feeling pleased when I hit upon the idea of thwarting the death squad that I expected would one day come to get me by running into the elevator and stalling it between floors. The idea was silly, I suppose, but I thought that if I could hold off my pursuers for a while, I stood a better chance of putting off the inevitable.

There was a problem with acceptance of death; I was never in a mood to accept torture. I thought if I could put up such a fight, then my would-be captors would have to kill me. The same idea came to James Neilson, who was my deputy. He told me that he carried an old-fashioned cutthroat razor that he intended to use against his attackers and then on himself. We were in agreement; they would never take us alive.

The Secret Police Arrive

Before I decided upon fatalism as an antidote to fear, I had a few lucky escapes, and these helped me to deal with the increasing realization that my time might be running out. When I was arrested on April 24, 1978, I guessed, rightly as it fortunately proved, that the heavily armed thugs from the secret police were not planning to "disappear" me when they came to take me away that afternoon as I was working in my office at the Buenos Aires Herald. Politely I asked the thugs where they planned to take me. They told me "Superintendencia de Seguridad," which was an annex of police headquarters where the cells for political prisoners were.

I had been there three years earlier when the Herald was raided one night by police commandos. I insisted on accompanying the newspaper’s city editor, Andrew Graham-Yooll, who was taken in for questioning. It was on this visit that I heard the screams of people being tortured. But Superintendencia de Seguridad was the site of a legal jail, not one of the regime’s clandestine prisons, and being imprisoned there turned out to be a useful experience.

On entering the underground cellblock I was greeted with the Argentine federal police’s welcome sign — a huge swastika covering an entire wall, with "Nazi-Nacionalism" written underneath it. Illuminating, too, was the time I spent in the infamous "tubos" — the vertical tubes that constituted the cells. The first one was lit only by the faint daylight from the air shaft far above. The second had a dim electric light. I was left alone long enough for myeyes to become accustomed to the gloom, and I was able to read the heart-wrenching inscriptions scratched by human nails on the walls. Judging by what these former prisoners wrote on the cell walls, they appeared to be very young and very religious. I saw only one militant proclamation of defiance. It was from a member of the self-styled Marxist-Leninist People’s Revolutionary Army. The other inscriptions were cries for help and were addressed to God or appeals to their mothers.

After an insider’s tour of four cells and two prisons, I ended up in a VIP cellblock ironically referred to as "el Hotel Sheraton." This was where notable prisoners were lodged temporarily while the military government decided what to do with them. Relatives bribed the guards and were able to bring food. Jacobo Timerman, the leading Argentine journalist at the time, whose book, "Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number," described what it was like to be in the belly of the beast, spent time there after his kidnapping and apparent disappearance aroused an international outcry. He read the same inscription on the wall of the communal shower: "Yankee, Get Me Out Of Here." Later he was plunged back into the netherworld of the Argentine military’s clandestine prison system where he was brutally — and pointlessly — tortured.

A secret of survival was a sense of humor. It was a comfort that the horror was not unrelieved horror. The wackiness of the military dictatorship was to be savored, and at the Herald we did that, along with trying, as best we could, to report news that the Argentine press was not able to publish. I saw our role as upholding a tradition that the newspaper had established during the 1946-1955 dictatorship of Juan Domingo Peron when, as one Argentine newsweekly put it, "The Buenos Aires Herald published in English what the other newspapers cover up in Spanish."

As the editor of the Herald, I was fortunate that the newspaper’s owners, The Evening Post Publishing Company, where I still work, were thousands of miles from Buenos Aires. That meant that I could decide what to report. So I went out as a reporter, first encountering women searching for their husbands or children who had been taken away by the "fuerzas de seguridad." With my wife we checked out such rumors we’d heard that the city’s crematorium was working overtime. We drove there at night and discovered that it was true, and we published stories about what we’d found. I went to many funerals, and we published reports of the missing.

My personal situation — and the newspaper’s — was helped in that the military leaders did not know what to do with me. They claimed they were fighting for democracy against international communism in some sort of a third world war. Eventually, for us, the job of running this newspaper became a matter of saving lives. Never was it more clear to me how vital journalists can be, especially when other societal institutions have lost their ability to be a counterbalance to destructive forces within. Of course, assuming such an oppositional posture moved against my well-honed instinct for taking an objective stance, but in the midst of a circumstance that was so surreal, abandoning this inclination didn’t seem a loss at all.

In 1979, I experienced a near kidnapping in which I was saved by the doorman of our apartment building who was a Jehovah’s Witness who had suffered under the military and knew that the Herald had spoken up for his religious peers. I decided to leave Buenos Aires when what I had not expected — what I had not factored into calculations about my own death — happened. Word reached me that the military would go after my wife and children. On December 18, 1979, my family and I left Argentina.

Robert Cox, a 1981 Nieman Fellow, is assistant editor of editorial and opinion pages at The Post and Courier in Charleston, South Carolina. He was editor of the Buenos Aires Herald from 1968 until 1979.