“The blast had not been an attack at all,” writes Griff Witte, the Islamabad/Kabul bureau chief for The Washington Post, about a deadly blast in a gunpowder shop in the center of Kabul, which many assumed to be an intentional act by the Taliban. “In a place like Afghanistan, we’re accustomed to seeing violence through the lens of militant Islam,” Witte says. “That, after all, has been the story—a war fought along religious lines, with insurgents fired by their desire to wage jihad against infidel occupiers. But it’s not the only story, and it’s easy to miss the others if religious motivations are instantly ascribed every time something goes up in smoke.”

Witte’s words open our collection of articles exploring the challenges journalists encounter in their coverage of Islam in the wake of 9/11. Words and images that follow Witte’s observations speak to these difficulties but also address ways in which journalists—and scholars who study Islam—are striving to anchor their work in a knowledgeable context and imbue it with essential layers of complexity.

Fawaz A. Gerges, a scholar of Islam and author, speaks to the challenge of “disentangling myth from reality about the political Islamic movement … [which] for journalists … involves a willingness to recognize the complexity and diversity within this movement … as they try to place their coverage of news and events (often involving violence and threats of violence) within a broader, more meaningful and accurate context.” In many years of working for and with Western journalists, Rami G. Khouri, a Beirut-based syndicated columnist, raises a profound professional challenge when he asks, “How do journalists make the lives and aspirations of Arab men and women who will not succumb to criminality or terror relevant to Western audiences?” Geneive Abdo, who reported extensively from the Middle East and Iran, observes that Western journalists demonstrate a tendency “to champion ‘secular’ or ‘moderate’ Muslims.” Yet, she writes, “for the vast majority of Muslims, such coverage is offensive not only because a small fringe is given massive exposure, but also because it is the media, not Muslims, who have the power to decide who speaks for Islam.”

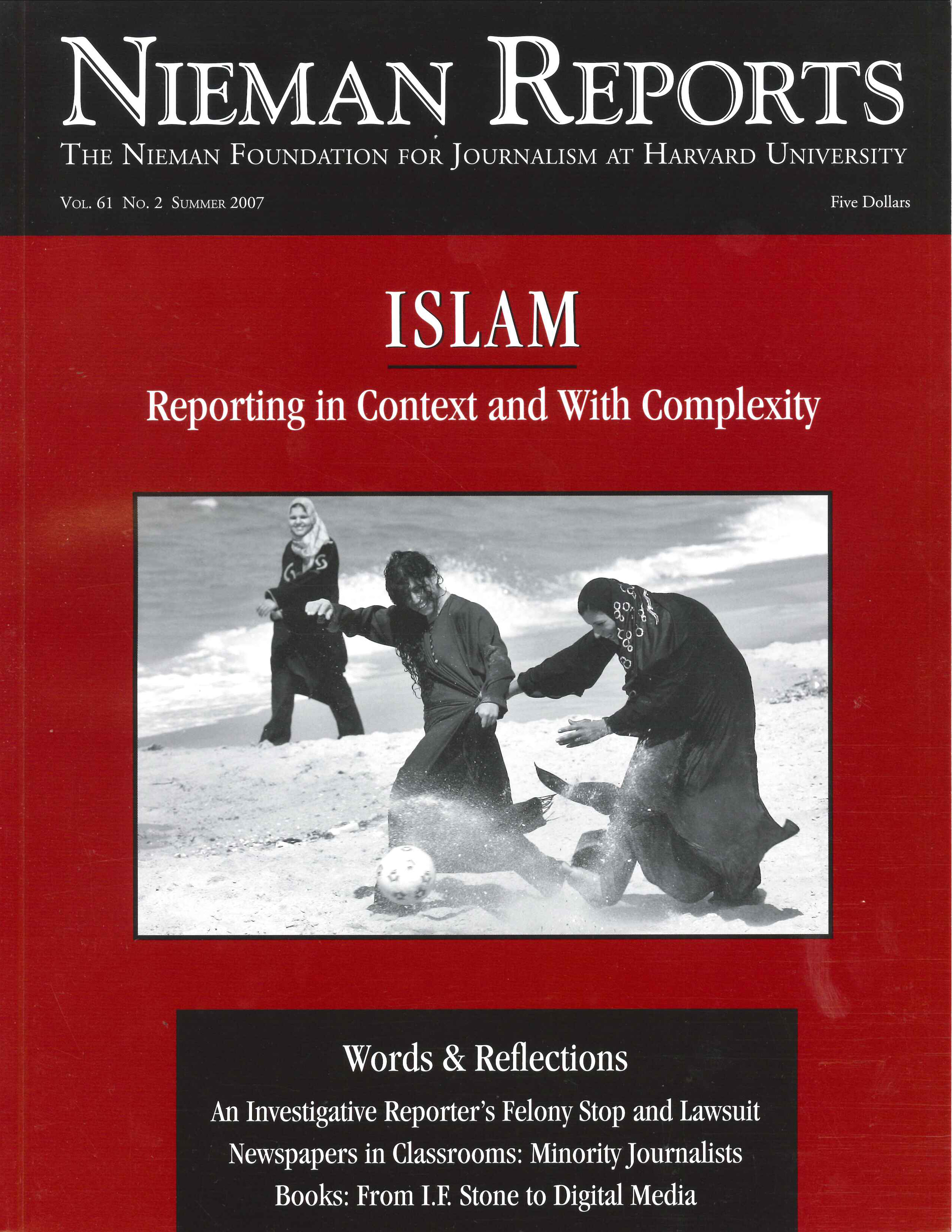

Richard Engel, Beirut bureau chief for NBC News, describes several layers of complexity about the “many wars within the war” and how the various power struggles in Iraq intersect with the conventional U.S. narrative. When he was Jerusalem bureau chief for Time, Matt Beynon Rees grew “steadily disillusioned with the ability of journalism to convey the depth of what I had learned about the Palestinians.” In writing a novel based on Palestinian characters, Rees found that “unlike journalism, it doesn’t depend on what characters say—its gets inside their heads.” Images and words by The Associated Press photographer Anja Niedringhaus display not only actions of war but convey the feelings of those affected, whether they are grieving parents or friends, frightened mothers with children, or girls who’ve found precious, rare moments of frivolity and joy.

At a time when Western coverage of the Muslim world is vast, Tariq Ramadan, a professor of Islamic Studies and an author, laments that “never has knowledge of Islam, of Muslims, and of their geographical, political and geostrategic circumstances been so superficial, partial and frequently confused—not only among the general public, but also among journalists and even in academic circles.” Since 1968 Robert Azzi has covered the Middle East as a photojournalist, and he provides ample reason to fault a lot of recent reporting on Muslims, as he contends that “Arab identities, positions and challenges need to be seen within their cultural context, not simply in relation to Israelis’ interests and narratives.” Bruce Lawrence, an Islamicist at Duke University, observes that “what we encounter appears to be the steady transformation of Muslims into ‘the Other,’ a defining of Islam as evil, and an ignoring of differences among Muslims.”

In writing about the jailing of Arab bloggers, George Weyman, managing editor of Arab Media & Society, finds in Western news coverage a mistaken belief on the part of journalists that “only those sharing a Western vision of modern society can freely exchange ideas and take part in engaged debate online.” Working in a region that he says is “among the most misunderstood and misrepresented,” Greek photojournalist Iason Athanasiadis often finds that “simple images told the story more effectively than sentences encumbered by qualifications, complicated by parentheses, and clogged by background.”

Ali M. Ansari, reader in modern history and director of the Institute for Iranian Studies at the University of St Andrews, focuses on the British sailors’ hostage situation in Iran to observe that “media coverage in Britain and other Western countries was driven by a master narrative that contained within it a number of assumptions related to Western supremacy.” It is the news media’s “calculated misuse of words, resulting in a distorted and inaccurate picture of a culture, a religion, and its people” that upsets Khaled Almaeena, editor in chief of Arab News based in Saudi Arabia, who writes that “reality gradually becomes subsumed by a new layer of misinformed belief ….” Marda Dunsky, who reported in the Middle East and now teaches “Reporting the Arab and Muslim Worlds” at DePaul University, believes that “journalism must not only give voice to Muslim attitudes but also probe and contextualize historical and political facts upon which they are based.” In her 15 years of traveling in the Middle East, German photographer Katharina Eglau has sought out the “often unnoticed details of daily life in a region best known for its turbulent politics,” and her images are found in her photo essay and interspersed through many stories.

Ray Close, who worked for the CIA for many years in the Middle East, explores the various threads that connect what good reporters and “successful spies” do. Working in Beirut, Daily Star reporter Iman Azzi witnessed last summer’s war with Israel; now with a paucity of international reporting about Lebanon, she writes that “when a major story erupts in Lebanon, Westerners don’t already have the dots by which they can make connections.” Photojournalist Alexandra Boulat’s collection of images of women and Islam, taken in Jordan, Gaza and Iran, “from refugee to pilgrim, from suicide bomber to teenager … speak to these women’s beliefs, rituals and habits, and to the anger and joy they experience.”

Andrea Elliott, who covers Islam in America for The New York Times and whose three-part series, “An Imam in America” was awarded the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing, writes about how, as a non-Muslim who did not speak Arabic, she found pathways to take her readers inside Muslim communities. “I came to realize that unless I focused on a single Muslim enclave—one mosque, city block, or family’s home—I would never capture a fuller story.” Susan Moeller, who directs the International Center for Media and the Public Agenda at the University of Maryland in College Park, describes findings from her center’s report of a review of U.S. newspaper reporting and commentary in which women were characterized as the “good” Muslims. Jamie L. Hamilton teaches about Islam at Phillips Exeter Academy and, in doing so, she contends with a media environment outside the classroom in which “the message that it is a ‘bad religion’ is so clearly consistent they [the students] don’t know what to think.” A glossary ends this section.

Nieman Reports is indebted to Robert Azzi for proposing this topic and helping us to bring such an extraordinary array of insightful voices to our pages.