I was just completing a 15-year project on veterans around the world, called “Afterwar,” when the Iraq War began in 03. Until that moment, the better part of my life as a photographer had been filled with images and stories of people who experienced war in Verdun and Danang and Stalingrad, with their haunted stares and memories. But as I flew to Bahrain and boarded a hospital ship filled with victims from the first days of the war, what had been past suddenly became present.

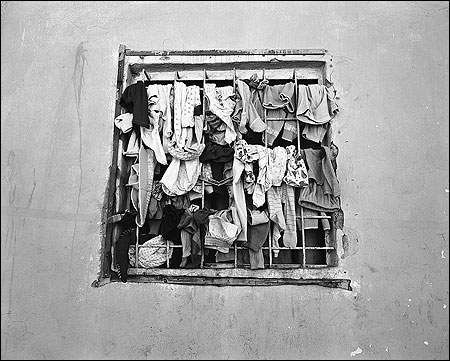

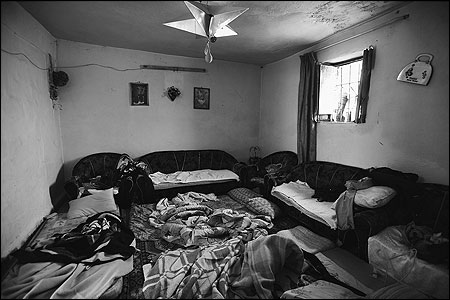

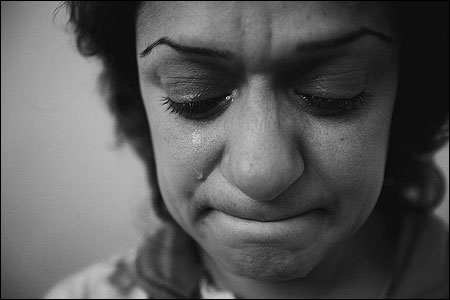

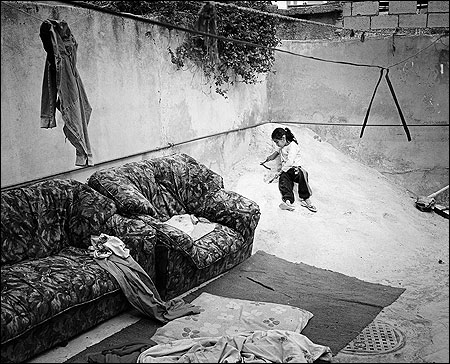

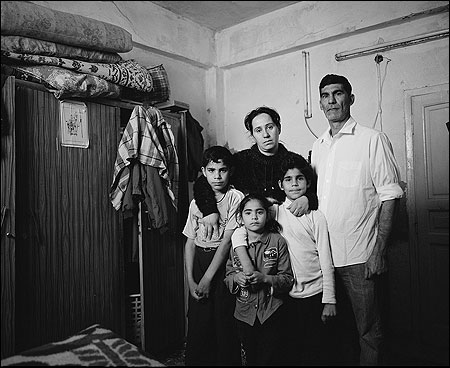

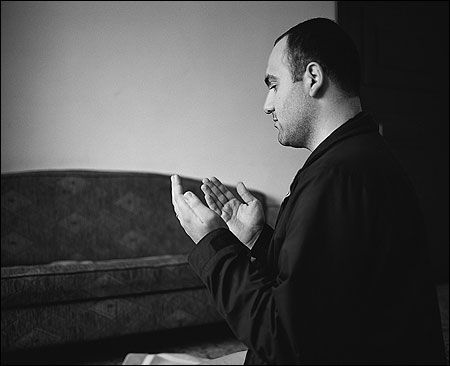

Survivors of the Iraq War are experiencing much of the same aftershocks as I’d seen in those from past wars. And like those older conflicts, part of this is created by the schism between private trauma and public denial. As we enter year six in Iraq, there is a serious lack of attention paid to the conflict’s greatest victims — the Iraqis, many of whom have fled their country to seek relative safety. The war follows them into cramped living conditions, forced inactivity, pain and scars of memory. They leave behind their livelihoods and possessions to get out alive. Families are broken, separated by thousands of miles. Others, unable to flee the violence quickly enough, also become its victim.

In April and September 2007, I traveled to Amman, Jordan, to work on two stories about Iraqis in exile. The first was about refugees, the latter about Iraqi doctors working with Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) in treating the wounded who, after recovery, must return to Iraq.

“Iraq: Scars and Exile” — through a multimedia documentary, produced by MediaStorm, a traveling exhibition, which opened at the Nailya Alexander Gallery in New York on January 9, 2008, educational outreach and panel discussions, a Web site and book — will demonstrate the toll of the war through these survivors’ faces, bodies and everyday lives. According to Refugees International, one in five Iraqis, nearly five million people, have fled their homes as a result of the violence since 2003. Rather than photographing hundreds of Iraqis to illustrate the epic size of the exodus, I chose to follow in an intimate way just a few; to take the journey with them, to live the aftermath of war with them, and to relate their experiences. Through their journeys, the needs, circumstances and emotions of millions who have been displaced by the war are addressed.

The U.S. government promised to resettle 7,000 of the more vulnerable Iraqis in the United States during fiscal year 2007; only 1,608 were admitted. For FY 2008, the commitment is to resettle 12,000, but so far fewer than 1,500 have arrived, and very few slots are available for the wounded. For those stuck in countries like Syria and Jordan, their living situation is rapidly deteriorating; most Middle East countries are now cracking down on illegal Iraqis, sending them to prison, or deporting them back to Iraq. And countries such as Syria and Jordan need more aid to deal with the Iraqi influx.

Wounds among the displaced are sometimes visible, sometimes inferred. By sharing their postwar experiences, viewers can learn about the true cost of war, its effects on a population, and come to understand more about their own relationship to conflict. Most people are unaware of what life has become for so many Iraqis. We see stories about U.S. soldiers and Marines. We get daily reports about suicide bombings and read accounts of civilian casualties. What we don’t see are Iraqi survivors, the hard-working, educated, family-oriented people — doctors, carpenters, engineers, teachers, homemakers, students — whom the American government invaded Iraq to set free.

Lori Grinker is a documentary photographer whose work focuses on Iraqis who’ve recently been resettled in the United States and others seeking asylum. Images and interviews from this project will be included in the multimedia documentary, exhibitions, educational curricula, and on her Web site www.lorigrinker.com