In 2004, as war raged in the eastern Congo over access to gold deposits, I waded with my camera through dirt and mud in a goldmine in Mongbwalu. Here gold was being mined, then shipped through Uganda to traders in Europe and Asia. Payments for the Congo’s gold enabled the purchase of more weapons and this prolonged the war that was terrorizing those living in this region with the brutality of rape and pillage.

Photographs I took on that trip were used in collaboration with Human Rights Watch to compile a report, “The Curse of Gold,” which examined in depth the reasons for it and the consequences of its continuation. Since those financing the war—the gold merchants—lived on other continents and were dependent on the continuation of this trade for their wealth, it was difficult to connect the pieces and harder still to make what was happening on the ground matter to those whose actions could make a difference.

In our attempt to bring this story to the attention of these international gold traders, Human Rights Watch and I worked together to create an exhibit of my mining photographs in Geneva, Switzerland, where Metalor Technologies, one of the leading gold mining companies, has its corporate offices. We invited to the exhibit’s opening night gold buyers and mining company executives as well as financiers, stockholders and journalists. Immediately after seeing this exhibit, Metalor Technologies halted its purchases of Congolese gold.

This experience convinced me that combining visual awareness with thorough research, like that done by Human Rights Watch, could create a powerful force for positive change. Clearly, this exhibit of my photographs opened minds and led to substantial changes in the company’s business policies.

After this breakthrough was achieved, the war in the Congo migrated to other regions of the country as other minerals and metals grew in value. Conflict flared in the Kivu provinces over mining access to coltan—short for columbite-tantalite and used in cell phones and computer chips—and cassiterite, a heavy dark mineral that is the chief source of tin.

In my mind, the question arose: How could my work as a photojournalist be used to confront these problems with similar success? By now, it was apparent that trying to create awareness through having my photographs published by a news organization was no longer viable in an industry struggling with its own set of problems. With circulation at publications of long-standing news organizations falling and Web sites—free to browse and enjoy—often tailoring content to attract particular audiences, budgets to support the work of those of us who take pictures in the midst of war and famine, natural disasters, and killing sprees are shrinking fast. With similar rapidity, places to publish our work are also disappearing. All of this is now forcing photojournalists like me to seek out alternative solutions for how to get our images in front of viewers, especially those whose awareness can likely spur action.

Challenging as they might be, these changes aren’t paralyzing. In fact, they can be invigorating. Markets evolve and practices change, and as they do it’s up to us to look for opportunities.

Recently, in Europe I taught a group of young students. When I asked how many read a newspaper in print, two hands went up. “How many read your news online?” Every hand went up. We have to rethink our audiences because if we do not react to that show of hands we’re going to lose this generation. They’re game-centric and on Facebook and Twitter. My niece and nephew are 14 and 17, and when I am with them, I think a lot about how I can make them and their peers the next generation of concerned people willing to become engaged in finding solutions. How do I reach them? How do I get them to understand that conflict is wrong?

People consume information—at least fragments of it—in much larger quantities than in the past. It’s my job to present this younger generation with visual images they will understand and find engaging. If they remain uninterested, it isn’t their fault. It’s mine.

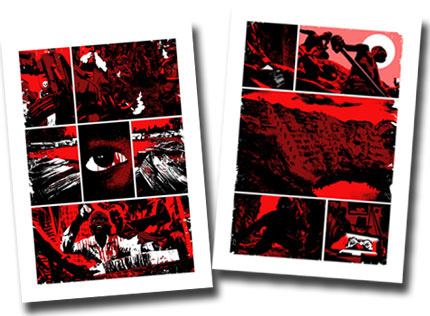

Taking a Comic Approach

At about the time I was teaching these young students, I was collaborating with a comic artist, Paul O’Connell, on an article for Ctrl.Alt.Shift. Our partnership revolved around the idea of us combining our various skills to create new ways of delivering messages. What this meant is that Paul took my photographs from places like the Congo and transformed them into a comic strip to tell the story to a different audience.

Comic readers are likely not to be your typical magazine reader. Our target was a different demographic and the results were outstanding. We reached the readers we set out to reach—heard back from them with positive praise—and were invited to exhibit our work in a leading London art gallery normally reserved for artists such as the British graffiti artist Banksy.

One step always seems to lead me to the next so now I am thinking of ways to build more roads to this younger generation. I find myself thinking about whether it would make sense for a photojournalist to team up with a software gaming company to create a trailer for the next big movie. Maybe in this way gamers could become aware of the exploitation of natural resources—and the effect it has on the people who live in these areas of the world—that go into producing the devices they use to play these games.

Instead of thinking about reaching a readership of a few hundred thousand people with a few photographs and a story, the ambition builds to promote awareness among millions—and to do so in a way that would even be fun for those doing the learning. That possibilities abound is what makes my work exciting again. We are in discussions with a large influential nongovernmental organization about a possible collaboration with Silicon Valley to connect with the people who play these electronic games.

Those who are the age of my niece and nephew aren’t likely to ever buy a magazine or newspaper but if the work of photojournalists can be partnered with these new avenues of distribution, this generation will be informed and engaged. That I can promise.

Marcus Bleasdale won The Anthropographia Award for Photography and Human Rights for “The Rape of a Nation,” which documents human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo.