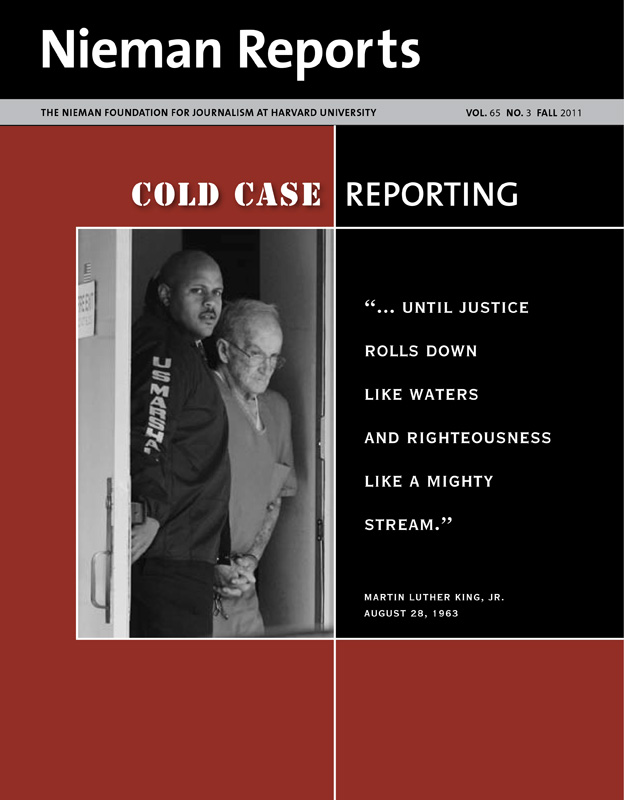

An officer books a suspect during a sweep of California farm towns aimed at breaking up one gang’s vast drug sales operations. Photo by Janjaap Dekker/www.janjaap.com.

In Spanish there is a lovely term, una tregua, that means a pause in hostilities, a cease-fire. I bring it up because it was during such a pause that I met with my friends Angela Kocherga and Alfredo Corchado, an affiliate and a fellow from my Nieman Class of 2009.

They had come from Mexico to Carmel, California for a weekend getaway. A place of stunning natural beauty, Carmel is an affluent coastal village of boutiques and cafes that’s only 20 minutes west of Salinas, the city where my beat is gang violence. Even seasoned reporters are often shocked to learn that California’s farm towns have gang murder rates on a par with Los Angeles, but Alfredo and Angela knew this.

That’s because the three of us report on the same phenomenon; we just do it from different vantage points. We cover the casualties of our continent’s never-ending war on drugs.

Alfredo, Mexico bureau chief for The Dallas Morning News, covers the supply side—Los Zetas and the other major cartels as well as the destruction they cause to Mexican society.

I cover the demand end in the United States, where gang kids sling dope and kill each other to protect this mega-business’s interests, down to the smallest street-corner drug market.

Angela is the border bureau chief for Belo Television in El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, the epicenter where the two sides come together in horrific ways.

On our three fronts, the scale of casualties is staggering. By some estimates, since 2004 there have been more than 40,000 drug war murders in Mexico and another 10,000 gang-related murders across the United States.

But on this day we weren’t dwelling on the war. The three of us settled in for an afternoon of wine and conversation at an upscale bistro. We sipped organic Pinot Noir from the nearby Santa Lucia Mountains and enjoyed the warmth after being caught in a rare June rainstorm. We were content to stare out picture windows and wait for the sun to poke through clouds.

I felt unusually carefree. I hadn’t been to a murder scene in months. In Salinas, an unheard-of 38 days had passed during which, police told me, no one tried to shoot a fellow human being. The spring brought continuous rains, and with them, the specter of peace.

Soon we were oblivious to our surroundings and back to talking about our beats. We recognized that we were passing through a zone of rare peace and luxury, and we felt fortunate. While those in the wedding party that surrounded us raised champagne flutes, we went on about shootings and murders with that callous cynicism reporters and cops pull off so well.

Angela wanted to know about the teenage Sureño gang members recently showing up at the Texas-Mexico border so I shared what I knew about them. Many were working as cartel hitmen, she said. Angela had worried about filming one of these kids for a recent news story, afraid that despite her best efforts, the boy might be recognized and become the narcos’ next victim.

I told her I understood. Protecting sources and even subjects on this beat is a tricky business.

Eventually a nicely dressed gentleman at the wine bar interrupted us to say he couldn’t help overhearing our conversation. We were suddenly self-conscious, ashamed, expecting this well-heeled guy to tell us to take it outside, that we had ruined the afternoon for everyone else in the place.

But he said none of that. The man told us he had always been concerned about the violence in Salinas. He asked what he could do to help.

The question shook us, pulled us out of our detached journalists’ stupor. The three of us had to acknowledge that we are more than observers and chroniclers of casualties—we don’t want any more kids to be murdered. We do our work with the far-fetched hope that people will see it and ask themselves what they might do to help.

As we finished our wine, I directed the man to a group of community leaders working for change in Salinas. After a walk down the hill to Carmel Beach and a stormy but brilliant sunset, we parted and returned to our respective posts on a high note of optimism, thrilled to see signs of real progress in both countries.

Police respond after a teenage boy is slain in Salinas, California. Photo by Janjaap Dekker/www.janjaap.com.

Alfredo went off to join Angela at the border to cover a peace caravan that brought Mexico’s intellectuals and leftists into an antiviolence movement they had until now largely ignored. Poet Javier Sicilia became a catalyst for this effort after his son was murdered and he condemned "the silence of the righteous." Mexicans from all social strata are now galvanized, demanding reforms to the nation’s failed drug policies and the corruption that surrounds them.

I flew east to attend a meeting at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, where a working group is researching and promoting a proven shooting-reduction strategy. It’s appropriately called Ceasefire and was developed in Boston with the help of Harvard researchers.

For the first time in the nine years I’ve worked this beat, I see smart people at last putting their heads together to try to stop the drug war’s carnage. Much of what they do is working, and I believe the effort is a big part of why the number of shootings has dropped dramatically in Salinas during the past two years.

Those of us who cover this war do not kid ourselves. The slaughter still rages, the killings picking up a rhythm we recognize too easily.

On a workday morning the same week the peace caravan arrived in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, three teenage boys were tortured, shot and hung from a bridge in Monterrey, Nuevo León.

In Salinas, the spring rains stopped and with summer the killing season bloomed again.

These developments are sobering, sickening. This does not mean we give up. It means we keep doing the work, and we just hold on tighter until the next tregua graces our days.

Julia Reynolds, a 2009 Nieman Fellow, is a reporter for the Monterey County Herald, where she covers youth gangs in California’s Salinas Valley.