This past summer a journalism controversy rooted in America’s troubled racial history erupted on the Web. A young, white female reporter, Mac McClelland, wrote for Good magazine about brief stints she’d spent covering Haiti for Mother Jones. She described how she dealt with the emotional fallout that resulted in a form of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after she witnessed Haitians living in dire poverty and experiencing violence. To cope in the aftermath, she had developed something of an obsession with “violent sex.”

The details McClelland shared in her June story were lurid and poignant: she described being so traumatized by the guns and by “gang-raping monsters who prowl the flimsy encampments of the earthquake homeless” that she began “fantasizing” about having sex at gunpoint. When she returned to the United States, McClelland wrote, she talked a former boyfriend into having sex with her in a way that would be “rougher” than anything she had ever experienced.

Her essay blazed a quick, hot path through the blogosphere. Soon a multiracial coalition of some 36 women scholars, activists and journalists, including Slate blogger Marjorie Valbrun and New York Times correspondent Ginger Thompson, both of whom spent many years covering Haiti, sent an open letter to McClelland’s editors at Good. On July 1, the website Jezebel, whose audience is largely young women, published this letter. In it, the letter’s authors said that they respected “the heart” of McClelland’s story about her trauma, but they objected to her portrayal of Haiti as what they called “a heart-of-darkness dystopia.” McClelland, they wrote, “makes use of stereotypes about Haiti that would be better left in an earlier century: the savage men consumed by their own lust, the omnipresent violence and chaos, the danger encoded in a black republic’s DNA.”

Their objections touched on issues long familiar to journalists of color when it comes to assigning stories. While editors demand that journalists of color justify their reasons for wanting to cover stories about ethnic minorities or the underclass, in some instances the motives of white journalists seeking to report on those same topics go unquestioned. At the core of this newsroom dynamic resides the usually unspoken question of whether non-minority journalists can accurately portray the full reality of what minorities experience without exploiting—or being perceived as exploiting—those they seek to cover.

The McClelland contretemps was only the latest iteration of this sticky dynamic. It’s an elusive if contentious subject that seldom rises to become a topic of media forums or workshops—except when minority journalists come together to talk. Valbrun wrote about McClelland on Slate and in doing so indicated her exasperation with white journalists parachuting into conflicts involving people of color in the United States or abroad:

I’m annoyed that people are often more interested in a story about poor black people/poor black country/genocide in the Sudan/etc. when the central character in that story is a white person. I mean all of Port-au-Prince is suffering from PTSD and I’m supposed to care about some woman who parachutes in for a couple of weeks and has the luxury to leave whenever she wants because she’s been inconveniently traumatized?These superficial pieces written by journalists devastated by what they experienced in troubled countries have become tiresome. They read like typical Hollywood scripts about a troubled country in Africa or urban America starring the noble, well-meaning white journalist, social worker, human rights activist, inner-city teacher, etc. If being in Haiti, or Bosnia, or Egypt, or Syria, or Libya is so damaging to these reporters’ psyches, perhaps they should stop reporting from these places. Writing these woe-is-me pieces just doesn’t cut it anymore.

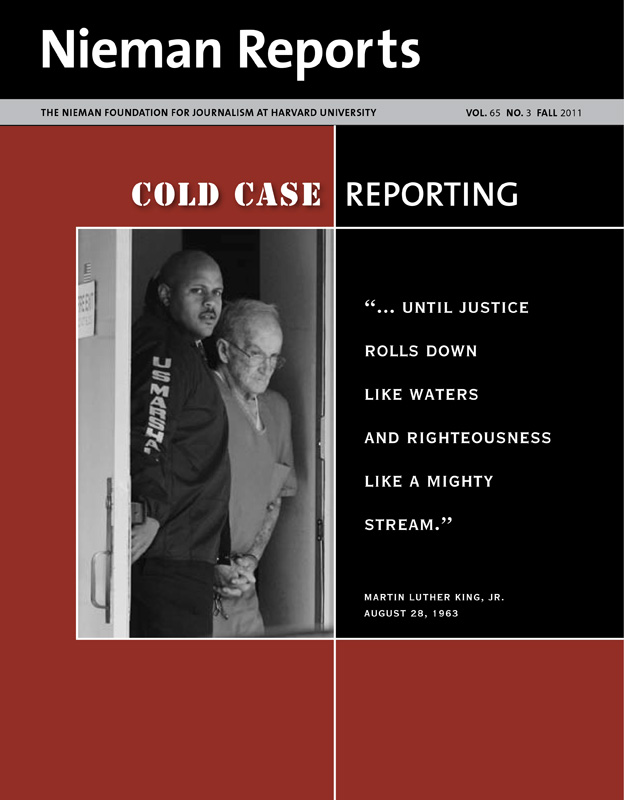

Of course, well-meaning journalists who are neither poor nor members of a racial minority have done exceptional reporting in these environments. And they’ve brought forth stories of abuse and corruption that have sped wide-sweeping and long overdue reform. Vivid examples emerge from the pages of “The Race Beat,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff about blacks and whites who did courageous reporting during the tumultuous times of the civil rights struggle in the Deep South. Today, dogged reporters, mainly white men, are excavating information about civil rights era racial crimes that had been dormant. Their reporting on these cold cases is an attempt to bring justice delayed during the 1950’s and ’60’s to family members of blacks.

I don’t know of any black journalists who will question the value and worth of these efforts.

Newsroom Dynamics

What concerns black journalists is the wider editorial latitude and the generous financial resources that some white journalists receive from their (often, but not always) white editors to pursue stories that minority journalists are sometimes denied. Then there is the high degree of attention and “pick up” that these race-sensitive stories by white journalists receive from other white journalists. From signs that are subtle and overt, a sense lingers among many black journalists that legitimate, important stories of hardship experienced by people of color are made extra legitimate if white journalists unearth them.

During the years I worked at daily newspapers, I watched this happen. It was sadly predictable and somewhat frustrating to see how editors tacitly favored those who looked like them with plum assignments and high-profile beats. Yet when I’d cover breaking stories involving blacks, my stories were routinely greeted with a high degree of skepticism—higher, I felt, than a conscientious editor would usually show. Editors would scrutinize my motives for wanting to do the story and then wonder aloud whether my treatment was “impartial.”

Over time I created work-arounds as a way to cope with what I saw as an intractable system of entitlement among whites. When I worked at a mid-sized paper in California’s Central Valley during the early 1990’s, I watched for two years as a white male reporter, who was talented, hard-working, and smart, developed a beat covering the burgeoning Southeast Asian population. After he was given months to dig into a particular issue affecting Hmong residents, he’d produce terrific stories that garnered attention and had impact. If I detected a whiff of smugness or hint of noblesse oblige emanating from this reporter when he returned to the newsroom after a lengthy reporting excursion, I kept it to myself.

In part, my strategy was about self-preservation; I was one of only two black journalists working on this newspaper’s metro staff in a newsroom of 50 full-time reporters and editors. And it wasn’t that I didn’t admire my white colleague’s gusto and intrepid nature. It’s just that I felt I had the ability to bring that same spirit and skills to coverage of the valley’s black residents. Yet I was stymied and constricted by editors who insisted that I stick to covering a small, affluent suburban town, then the local school district, then the higher education beat. During those two years, I sometimes felt I would have to spend a decade at that paper before editors felt I had “earned” the kind of stature and reportorial freedom that I felt I deserved.

Looking back, I realize being assigned to those mundane beats grounded me in fundamentals and seasoned me for the time when I’d be on the beat I wanted. With my editor’s demand for verification, speedy writing, and absolute accuracy, I picked up the essentials of reporting. In my third year at the paper, following a change in the editorial leadership, I was given the chance to develop a minority affairs beat, and soon I was covering the stories I’d imagined doing during those first two years. All that I’d learned—and demonstrated—while covering those other beats and local news undoubtedly bolstered my pitch to these new editors.

Now the Internet is upending nearly everything about how news is covered, distributed and absorbed. Part of this shakeup affects decisions about which stories are covered and how much reporting time a news organization devotes to any story, including those involving marginalized groups. At the same time, digital media outlets are opening up a landscape ripe for independent voices; websites such as Good, Slate and less well-known digital entities are springing up as platforms where people and issues that previously went begging at the door of big, corporate newsrooms can now get attention.

Still to be resolved, however, is the huge issue of the digital marketplace for stories about ethnic minorities and communities that historically have been on the margins: Will consumers look to—and find—reliable, accurate coverage on new websites? Or can they rely on legacy news organizations for expert coverage of their concerns and experiences? Also, who are the journalists who will report about the poor and people of color—and for what kind of news organizations?

And a final question that must be asked: In the future, in a media ecosystem in which click-throughs and pageviews are measured with the precision of a Swiss watch, will reporting and commentary about minority communities be meaningful contributions to society or one-off flash points that generate more heat than light?

Amy Alexander, a Nieman affiliate in 1996, is author of several books, including “Lay My Burden Down: Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African-Americans,” coauthored with Dr. Alvin F. Poussaint. “Uncovering Race: A Black Journalist’s Story of Reporting and Reinvention” is being published in October by Beacon Press.