During his presentation at the Nieman Foundation, Sacco showed some of the photos he took in the Gaza Strip. Photo by Lisa Abitbol.

When Joe Sacco and Chris Hedges traveled to the Gaza Strip in 2001 for Harper’s magazine, they researched a little-known mass killing from 1956. But when the piece, written by Hedges and illustrated by Sacco, was published, editors had cut the entire section about Israeli soldiers killing hundreds of Palestinians during the Suez crisis.

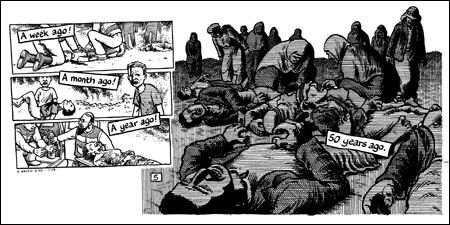

That snub inspired “Footnotes in Gaza,” Sacco’s celebrated 2009 long-form comic book. Shifting back and forth between 1956 and the present day, he describes the killings of nearly 400 Palestinians in the neighboring towns of Khan Younis and Rafah.

“It irks me that history is always the first thing that gets cut out,” Sacco said, while recounting the incident to an audience at the Lippmann House in late February.

In this panel from “Footnotes in Gaza,” Joe Sacco takes a long view of violence in the Gaza Strip, looking back to 1956. Image courtesy Joe Sacco.

Sacco and Hedges, a 1999 Nieman Fellow, have been friends since they met in Bosnia years ago. Their most recent collaboration is “Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt,” a book about poverty in the United States that focuses on four of the hardest-hit regions. Nation Books is due to release it in June.

While Sacco’s books are acclaimed and widely available now, the journalist-cartoonist faced stiff resistance starting out. For his first book, “Palestine,” he traveled to the region on his own dime—“and I didn’t have many dimes,” he said—and originally published it as a series of comic books, each one selling worse than the one before.

His use of cartoons to tell a story may have turned off editors, but his books are the result of meticulous research and reporting. He juxtaposes quotes from survivors and witnesses with his illustrations of their ordeals, relying on archival photos to get the look right.

He did acknowledge “a certain tension between using an accurate quote and interpretive drawing,” but said that it was necessary to get the story across. “My standard, if at all possible,” Sacco said, “is to show things the way they were.”

While in the field, he takes photographs and copious notes. They help him get into the minds of his subjects when drawing them, especially when it comes to their faces. But that process can be even more emotionally draining than interviewing survivors about what they saw.

“As a journalist, you’re kind of a technician or a clinician in the field,” he said. “It’s a very cold profession when it’s done well. … But when you’re drawing, you can’t escape from the scenes you were told.”