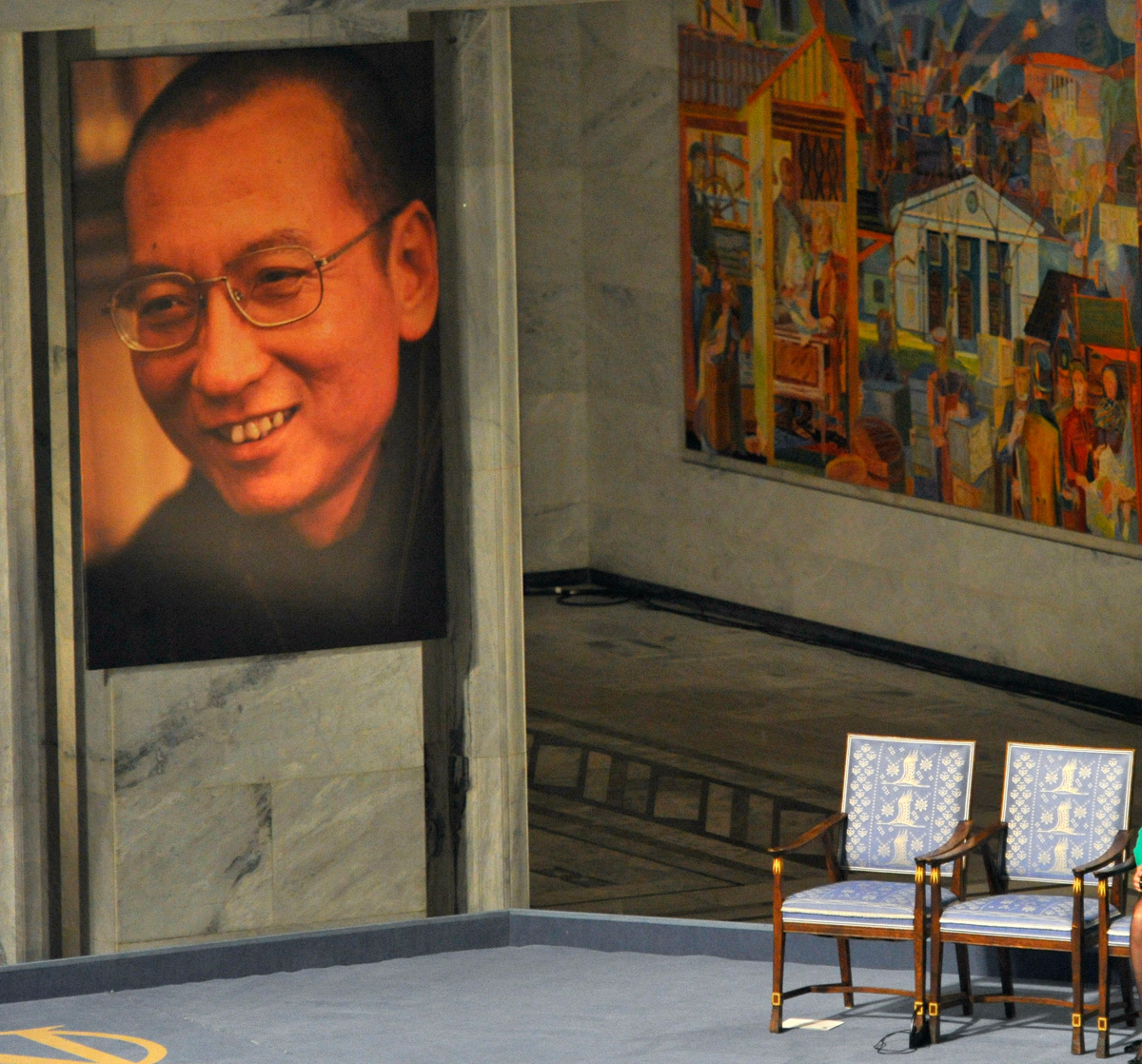

China is the only country in the world with a Nobel Peace Prize winner in prison. Liu Xiaobo, pictured above, missed the 2010 ceremony in Oslo, Norway

In 1948, the Harvard Sinologist John King Fairbank wrote, “China is a journalist’s dream and a statistician’s nightmare.” It was, he explained, a place “with more human drama and fewer verifiable facts per square mile than anywhere else in the world.” Sixty-five years later, much of Fairbank’s description rings true, even as we find ourselves drawn even more urgently by the need to make sense of China’s metamorphosis, its contradictions, and the growing role that it plays in our lives around the world.

When I studied Mandarin, in Beijing, for the first time in 1996, the Chinese economy was smaller than that of Italy. The countryside felt near: Most nights, I ate in a Muslim neighborhood, where tin-roof restaurants kept jittery sheep tied out front. The animals vanished in the kitchens, one by one, at dinnertime.

By 2013, China had the world’s largest Internet population—a raucous, questioning, but still censored realm—the largest number of new billionaires and new skyscrapers, and an economy second only in scale to the United States. China’s rise has created vast wealth and power—but also corruption, a new awareness of inequality, and a growing demand in China and abroad for an understanding of who has profited and at what cost.

For journalists, China’s rise presents a set of puzzles that we cannot escape. The first is practical: As journalists in China, foreign or domestic, how do we navigate the obstructions erected by the Communist Party, and then limit the consequences to those who dare to speak? This is the most obvious challenge, but also, perhaps, the most familiar, and the tools we use are those which serve correspondents in any country: persistence and ingenuity, sure, but, more important, the journalist’s version of the Hippocratic Oath—the determination to do no harm to sources in a nation that regards their voices as a threat.

The more novel problem is one of proportions: In a nation of such profound contrasts—between new freedoms and old forms of repression, between extraordinary fortunes and persistent poverty—how many words should we dedicate to the fact that China has never been more prosperous—and how many words should we spend on the fact that it is the only country in the world with a Nobel Peace Prize winner in prison? (That’s Liu Xiaobo.)

Lastly, and perhaps most difficult, the puzzle of covering China is one of access: What is a reporter and a news organization to do in a country that is increasingly denying access to journalists who publish work that the government finds threatening? Over the past two or three years, the Chinese government’s view of the foreign press has changed in two important ways: In 2011, the Arab Spring unnerved the Chinese leadership more than any event in a generation with the demonstration of how information and organization could undermine authoritarian governments that appeared to be stable. At the time, Chinese authorities publicly criticized foreign correspondents, whom they blamed for covering Chinese activists who were inspired by events in the Middle East.

In 2012, with China’s new wealth soaring, foreign news organizations ratcheted up their scrutiny of China’s politicians—and their personal fortunes—to a level of forensic detail that we have rarely, if ever, seen in foreign correspondence. Reporters documented how the families of China’s then-premier Wen Jiabao and its incoming president, Xi Jinping, had assembled enormous fortunes while their relatives were in office.

In retaliation, the government blocked the websites of The New York Times and Bloomberg News, which had led the new wave of investigations. Authorities also barred Chinese banks and other institutions from adding contracts for new Bloomberg terminals, and it blocked news organizations from adding new staff or replacing existing correspondents in China. The purpose was to pressure the business operations of news organizations that were already imperiled by the pressures of the Web. (That approach was also applied to The Washington Post and Reuters.)

Historically, journalists anticipated that they might be denied access to China if they covered hot button issues like human rights. (That rarely stopped them.) But, now, reporters and their employers are punished for exposing the private wealth of senior Party leaders. And that reflects a fundamental shift in the role that foreign correspondents play in China. We are no longer bringing home news to an American audience from a faraway land. China is a rising superpower, and an audience of readers. It is so present in our economic and political lives around the world that it has forced journalists to step up the quality of their work. Whether we like it or not, foreign correspondents are now active participants in the domestic conversation about the distribution of power and resources in the world’s greatest economic boom. Even when a story in the Times is blocked by the censors, it finds its way to readers in China.

This is a new iteration of an old responsibility: As foreign correspondents, we have always faced the task of recording the memory that people in other countries are not permitted, by circumstance or by force, to record themselves. In the past, that has often meant documenting war and dissent. But in China today it also means documenting the world’s most rapid accumulation of assets, and the sorting of winners and losers—a process that will have consequences for generations to come.

We are reporting on not only a country, but also a contest over the values that China will project as a new power in the world. It is an ongoing, unfinished debate about the definition of truth, accountability and power. It is a privilege and a responsibility to take the measure of this moment. Fairbank was right. It is a hell of a story.

Evan Osnos, a staff writer at The New Yorker, adapted this essay from his Joe Alex Morris Jr. Memorial Lecture delivered on Nov. 14, 2013 at the Nieman Foundation

Evan Osnos delivers the 2013 Joe Alex Morris Jr. Memorial Lecture