Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, who left office in March 2013, was the focus of a 2012 New York Times story about corruption

In the fall of 2011, while researching a story on China’s business elites for The New York Times, I made a startling find: a set of corporate documents that linked the relatives of then Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao to more than $2.7 billion in assets. The records, obtained during a government document search, showed that some of the prime minister’s closest relatives, including his brother, son and daughter, had over the past decade acquired major stakes in scores of companies—diamond and telecom ventures, property and construction concerns, and one of the country’s biggest financial services companies, Ping An Insurance.

How, I asked myself, could such sensitive and potentially explosive information turn up in Chinese public records?

The answer, I have since concluded, was simple. China’s rapid economic growth has given rise to a phenomenal shareholding boom and a public records system that is far more advanced and transparent than I had imagined. Journalists working in China can now get detailed records on the finances of the country’s biggest state-run entities and access to the names of investors in tens of thousands of public and private companies. They can peer into one of the country’s darkest secrets: how the families of the nation’s political elite accumulate wealth.

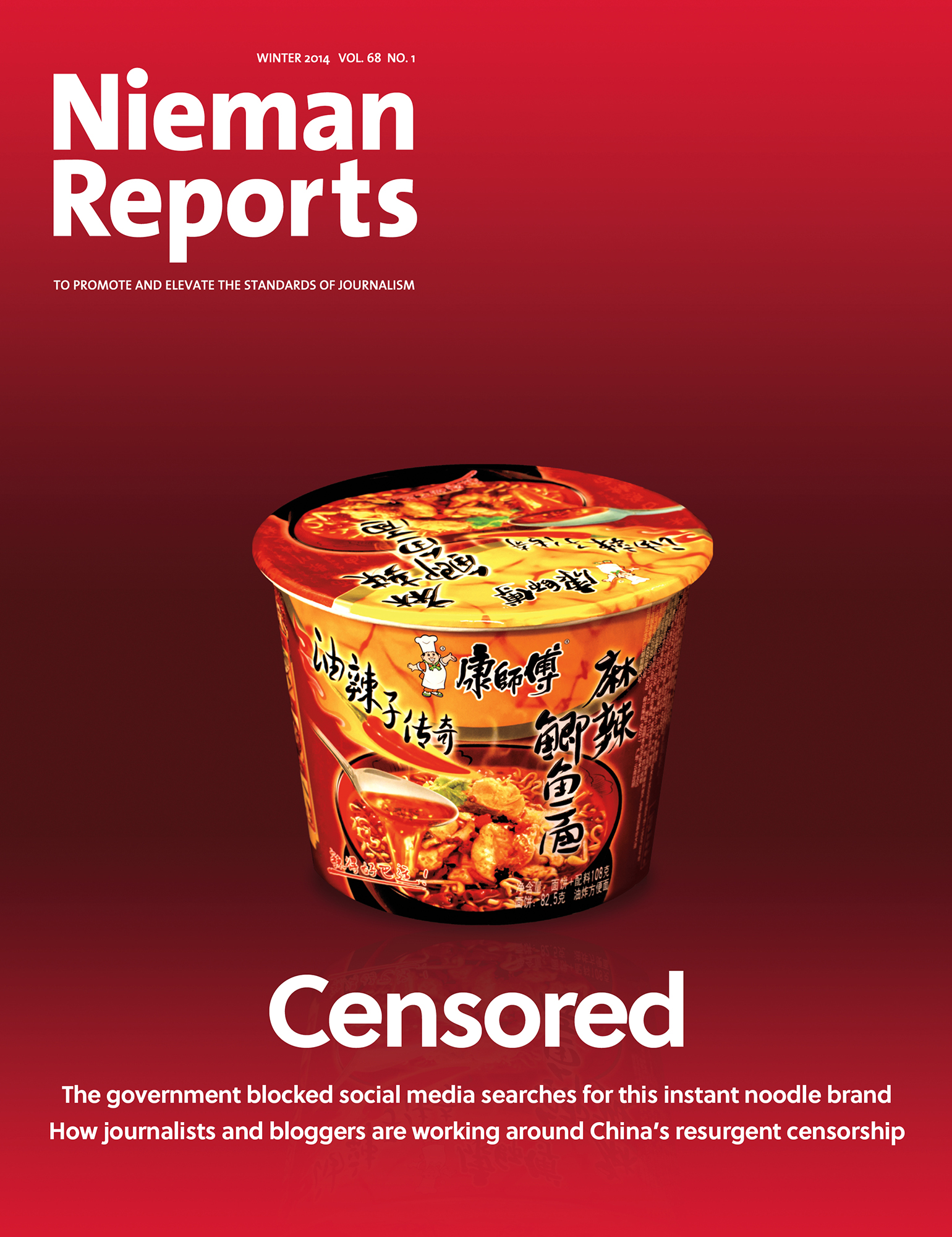

Publishing such information, of course, remains a challenge. The Chinese media are largely barred from reporting on the families of the Communist Party’s top leaders. And in 2012, after Bloomberg News and The New York Times published a series of articles on the enormous wealth of China’s ruling elite, the Chinese government blocked the websites of each news organization and tightened its surveillance of foreign journalists in China.

And yet, it’s likely that in the next decade much more will be written about the hidden wealth of Chinese leaders. China is rapidly integrating into the global economy, with Western investors taking stakes in Chinese startups and Chinese companies acquiring assets overseas. As China becomes more international, it will be more difficult to hide large stakes in public and private companies. In other words, there’s no easy way to turn back the clock on investigative reporting involving Chinese businesses.

Evan Osnos on the New Forensic Reporting in China

From the 2013 Joe Alex Morris Jr. Lecture

I have often been asked how I discovered the corporate records linking the family of the former prime minister to billions of dollars in assets. I often ask myself something else: What took me so long to do so?

I have two theories. First, many Western journalists, including me, were concerned about the risks involved in investigating China’s top leaders. There was always the threat of losing one’s journalism visa. Second, there were doubts about whether public records and shareholder lists even existed.

The records did prove complex. Although I began collecting records in late 2011, it took more than a year to make sense of much of what I discovered because the Wen family and their business partners had set up a network of shell companies and investment vehicles, many of which constantly changed their names and moved locations.

What I found, though, is that the same principles that apply to reporting in the U.S. also apply in China. Investigative reporting has always been about being patient and determined; knowing how to slowly put the pieces of a puzzle together, just like good detective work.

After my articles were published in 2012, conspiracy theories emerged in China, with some Hong Kong newspapers claiming that I had received a box of documents from the prime minister’s enemies. It was much simpler than that. I requested documents and followed the money. In the end, I called some of the prime minister’s relatives. And to my surprise, they didn’t hang up.

David Barboza, Shanghai bureau chief for The New York Times, received the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for his investigation into corruption in China