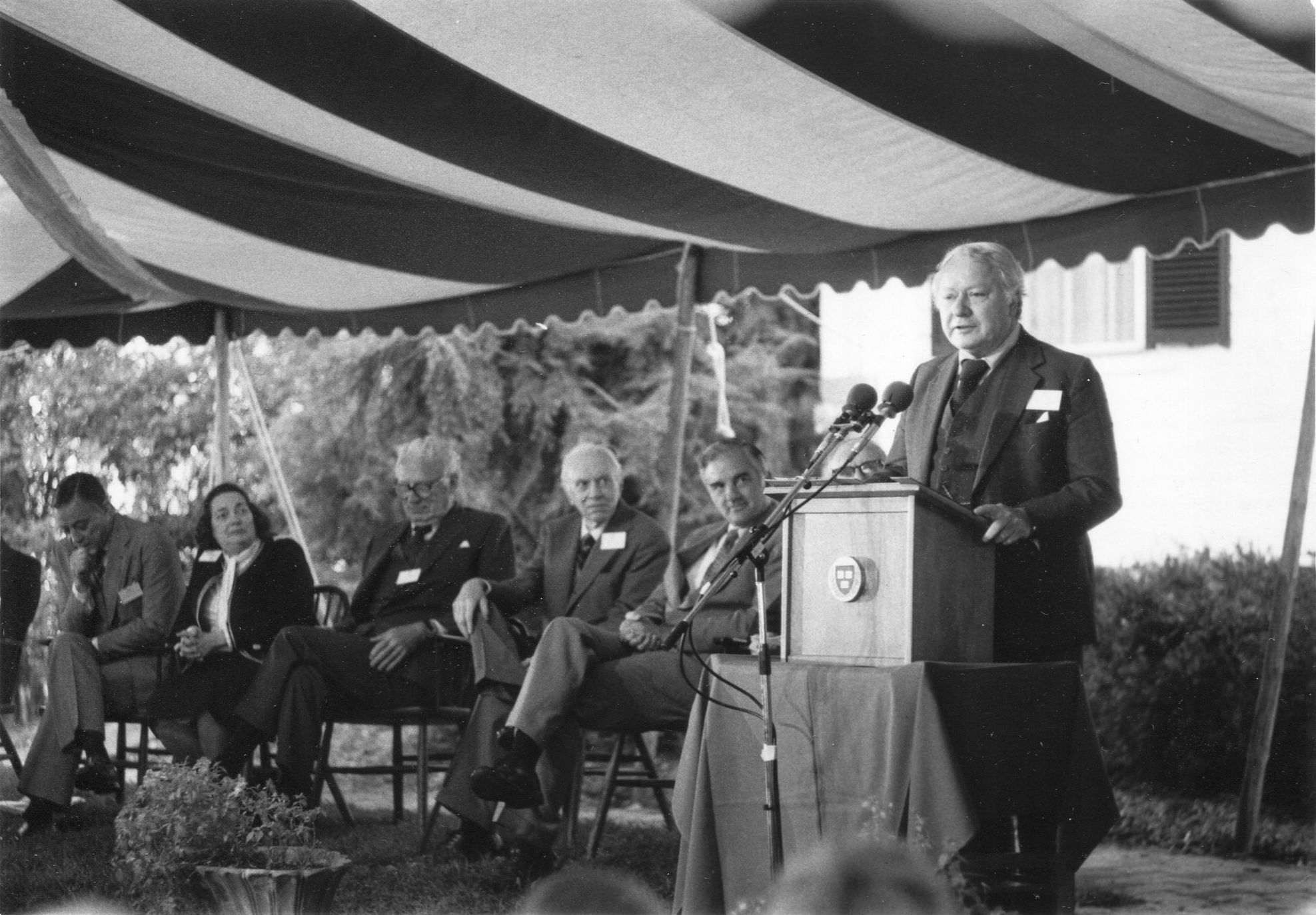

Curator James C. Thomson, Jr. welcomes guests to the dedication ceremony for Walter Lippmann House on September 23, 1979

For its first 40 years, the Nieman Foundation was something of a nomad. It had been created in 1938 through money left to Harvard by Agnes Wahl Nieman, the widow of Milwaukee Journal editor Lucius Nieman, and university president James B. Conant was skeptical of its long-term prospects. As such, the Foundation had no permanent home. It moved from place to place on and off campus during those early years, none of which provided adequate room for Fellows to host their own events.

That changed in 1977, when the university gave the Foundation a white Greek Revival house on the edge of campus, along with a $100,000 grant for repairs and renovations from the estate of Walter Lippmann, one of the school’s most famous journalistic alumni, who had died in 1974 at age 85.

The building’s foundation predates the Nieman Foundation by a century. It was built in 1836 by Ebenezer Francis, a carpenter and Harvard custodian, on the street that now bears his name. Francis died in 1886 at age 96, and his family sold the house in 1921. It passed through many hands from there, serving as a secretarial school, a kindergarten, a home for visiting dignitaries, and a church parsonage before Harvard bought it in 1974.

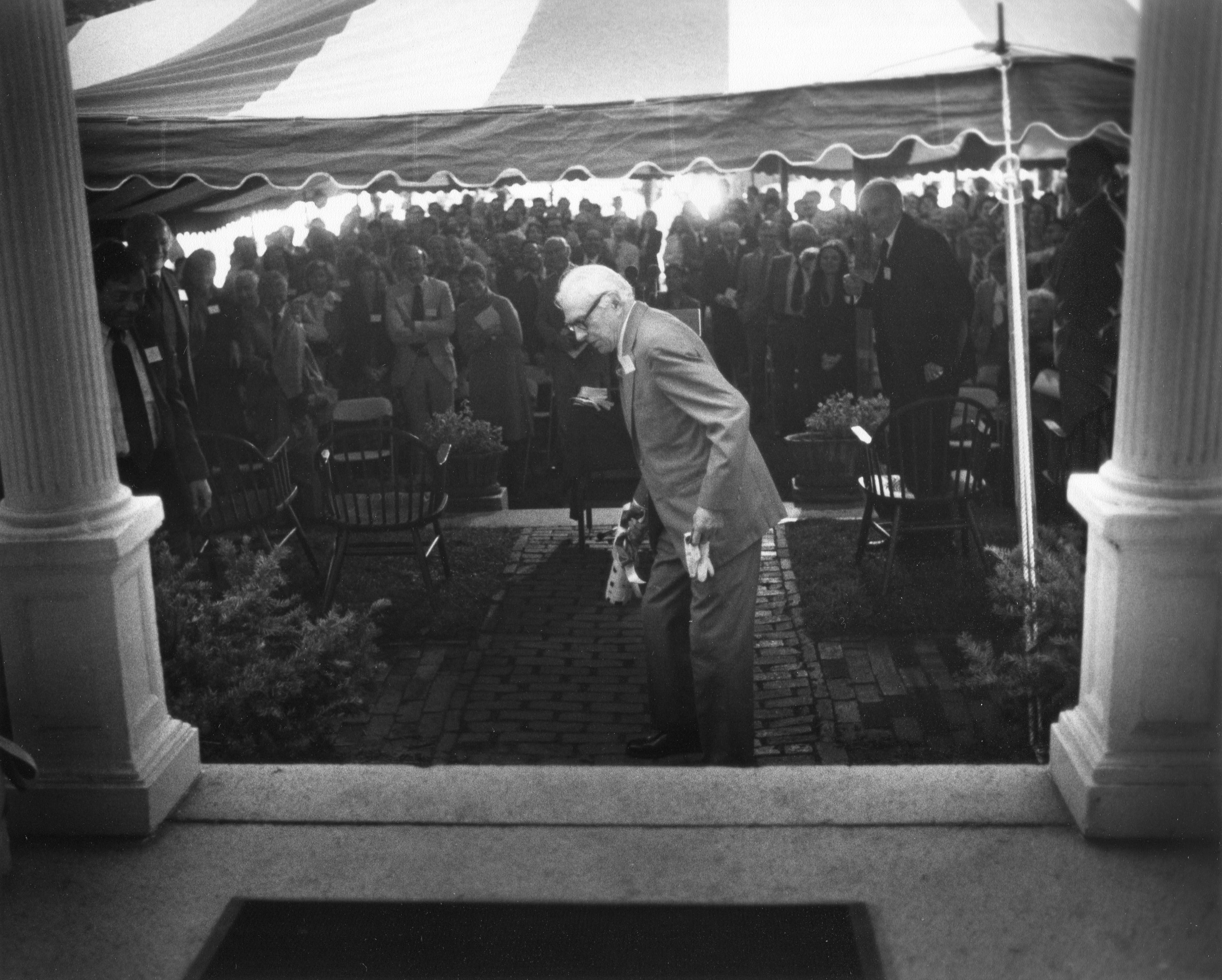

The Foundation moved into the building in January of 1978, though it wasn’t until September 23, 1979 that it was formally christened Walter Lippmann House, on what would have been the journalist’s 90th birthday. More than 350 guests attended the dedication ceremony hosted by curator James C. Thomson Jr., featuring Lippmann biographer Ronald Steel, Washington Post executive editor Benjamin Bradlee, former curator Louis M. Lyons, Harvard president Derek C. Bok, former curator Archibald MacLeish, and New York Times columnist James Reston. Transcripts of the ceremony ran in the Winter 1979 issue of Nieman Reports.

“Now Jim Thomson invited us here to a dedication, but he didn’t say what the Lippmann House was being dedicated to,” Reston said at the ceremony. “I suggest that it should be dedicated to the ideal Walter had in mind, of bringing the thought of the University into the daily press, and also the personal ideal of living the private life of a professor, at the salary of a columnist.”

Lippmann was an ideological lodestar for the Fellows, someone who “perfectly symbolizes the very program to which the building involved is dedicated,” as president Bok said in his comments. Lippmann, a co-founder of The New Republic and one of the most respected journalists of his era, was best known for his coverage of national politics and public affairs in his nationally syndicated column “Today and Tomorrow.”

“He was the presiding journalist of the age, because he remembered things in a country that has no memory, and related the day’s news to the past and the consequences of the future,” Reston said. “In short, he made people read and even think about his thoughts on the latest thunderclap in the news, including even officials. This is quite an achievement.”

He had also attended Harvard as an undergraduate and later served on its board of overseers, where he was instrumental in convincing president James B. Conant to use the Nieman bequest to create a Fellowship program. Though he had declined a professorship offered by Conant, he did have a reputation as a mentor to younger journalists. Bradlee, the son of one of Lippmann’s family friends, recalled some of his encounters with Lippmann when he was starting out in Washington: “In those years, Walter was the powerhouse journalist of his times: authoritative, commanding, and yet extraordinarily unpretentious with us beginners—extraordinarily generous with his time, and his encouragement. He was the first big shot journalist I ever knew who listened as much as he talked.”