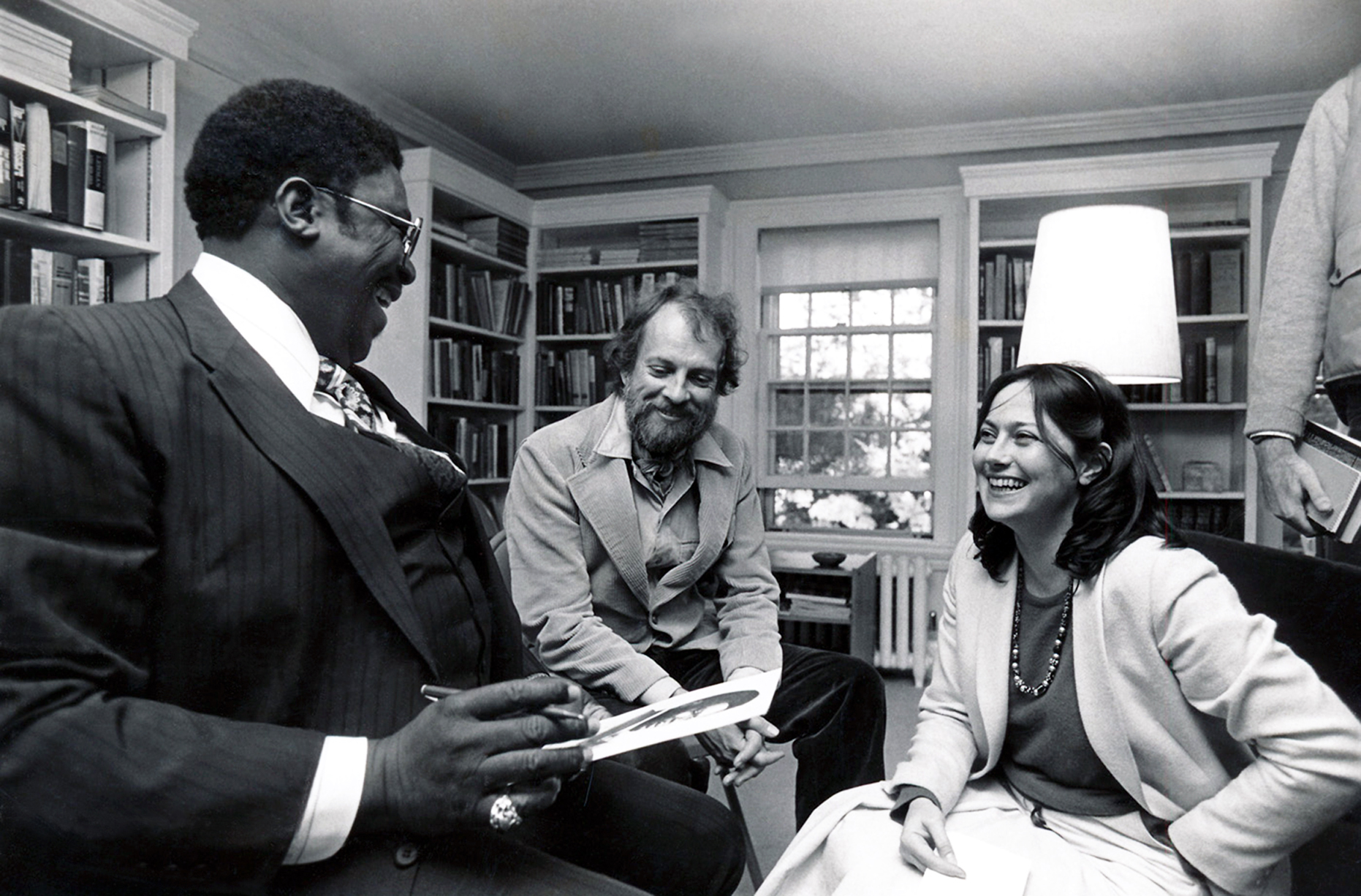

Nieman Fellow Bistra Lankova, right, and Charles Sawyer thank B.B. King for giving the blues talk and concert at Lippmann House

The story of B.B. King at Lippmann House would not be complete without more information about Bistra’s background: Bistra Lankova was a producer with the film department of Bulgarian National Television in Sofia. She came to Harvard after spending the spring semester at Columbia University, studying with the great Czech producer and writer, František (Frank) Daniel. The Nieman selection committee had been actively seeking journalists from countries in the Eastern Bloc, and when she checked in with the Bulgarian Consulate in New York, she saw their recruitment notice and applied.

But getting out of Bulgaria in the first place had not been easy. Her department at National Television had approved her journey abroad to Columbia for “specialization,” but the Interior Ministry denied her application for an exit visa. Someone, a jealous colleague, perhaps, had anonymously put a poison-pen letter in her dossier, saying that she was politically unreliable and should not be allowed out of the country.

Infuriated, she called the office of President Todor Zhivkov, whom she knew personally. He granted her an audience. She had considerable standing with the president because of her family’s history. Her late father, the poet Nikola Lankov, had been chairman of the Bulgarian Writers’ Union and editor in chief of the country’s main literary magazine. In fact, he had opposed and had been imprisoned by all the “right” regimes: the czarists in the 1920s, the fascists during World War II, and the Stalinists in the early 1950s. Bistra had never before made a personal request of the president, but in her meeting with him in the fall of 1979 she told him that if the name “Democratic Republic of Bulgaria” meant anything, the daughter of the Proletarian Poet, Nikola Lankov, should not be prevented from leaving the country.

He picked up the phone at once and gave the order to issue her exit permit.

When Bistra and I met near the end of her Nieman year she was already making plans to return to Sofia. Our romance blossomed quickly, and I realized soon after B.B.’s visit at Lippmann House that our relationship might not survive if she returned to Bulgaria, where marrying a foreigner required state approval and permission to leave the country after marrying might not be forthcoming. After much soul searching and long discussions she decided to immigrate so we could marry. We joked that it was a marriage of inconvenience, because it then took two years for her to get a green card and another three before she could become a U.S. citizen. We never had cause to regret our decision, though it meant that she would be separated from her native country for another five years.

On the day after Thanksgiving, November 25, 1988, Bistra died in an auto accident when a drunken driver (blood alcohol level .28, legal limit .08) jumped the median on Route 16 in Revere, Massachusetts, became airborne, crashed into a passing gasoline tanker and landed on top of our car. Bistra was in the passenger seat. I was at the wheel. She died in Massachusetts General Hospital shortly after the collision. I was injured and spent months recuperating. The driver of the other car was pronounced dead at the scene.

Nieman Foundation curator Jim Thomson eulogized Bistra at a memorial held at Tufts University in December of 1988. He recited from memory a poem by A.E. Houseman that he had first heard when Bistra recited it at the farewell gathering of her Nieman class in 1980:

Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

A Bulgarian translation was read at her graveside in Sofia in January 1989.