A woman holding her baby near Peshgapur, Iraq. Displaced Iraqis had come here to take advantage of the river's water supply.

Looked at from a certain angle, the United Nations could be the world’s biggest news organization, with well-staffed bureaus in most crisis zones. Rather than one harried correspondent covering everything across several countries, the U.N. has desks dedicated to human rights, democratic elections, political dialogue, security sector reform, and women’s empowerment. To a journalist, it seems like an extraordinary luxury—but also an attractive opportunity, as budgets for foreign coverage and foreign postings continue to shrivel.

This trend is just as much a reflection of the rising danger and diminishing returns for journalists in today’s media environment as an expression of the U.N.’s efforts to entice top media practitioners to communicate its messages to the world.

In 2009, I was arrested and detained in Iran while covering the violent demonstrations following the presidential election. I was released after three weeks in a Tehran jail. But it could have been a lot worse and served as a wake-up call to how dangerous our profession was becoming. Since then, it’s become clear that cost-cutting news organizations—increasingly dependent on freelancers and cheaper, high-quality technology—were lowering the bar on who could lay claim to being a journalist. The Internet was democratizing information even as Twitter’s universality eroded the allure of a remote byline. At the same time, armed groups, both ideological and criminal, started targeting journalists on an unprecedented scale. All this reduced the space within which foreign correspondents could function. It soon became obvious that at best, many of us were destined to become curators of information largely provided by others; at worst, we would be unemployable.

Hundreds of displaced Iraqis were living in the Baharka camp earlier this year. This smiling boy is just one of them.

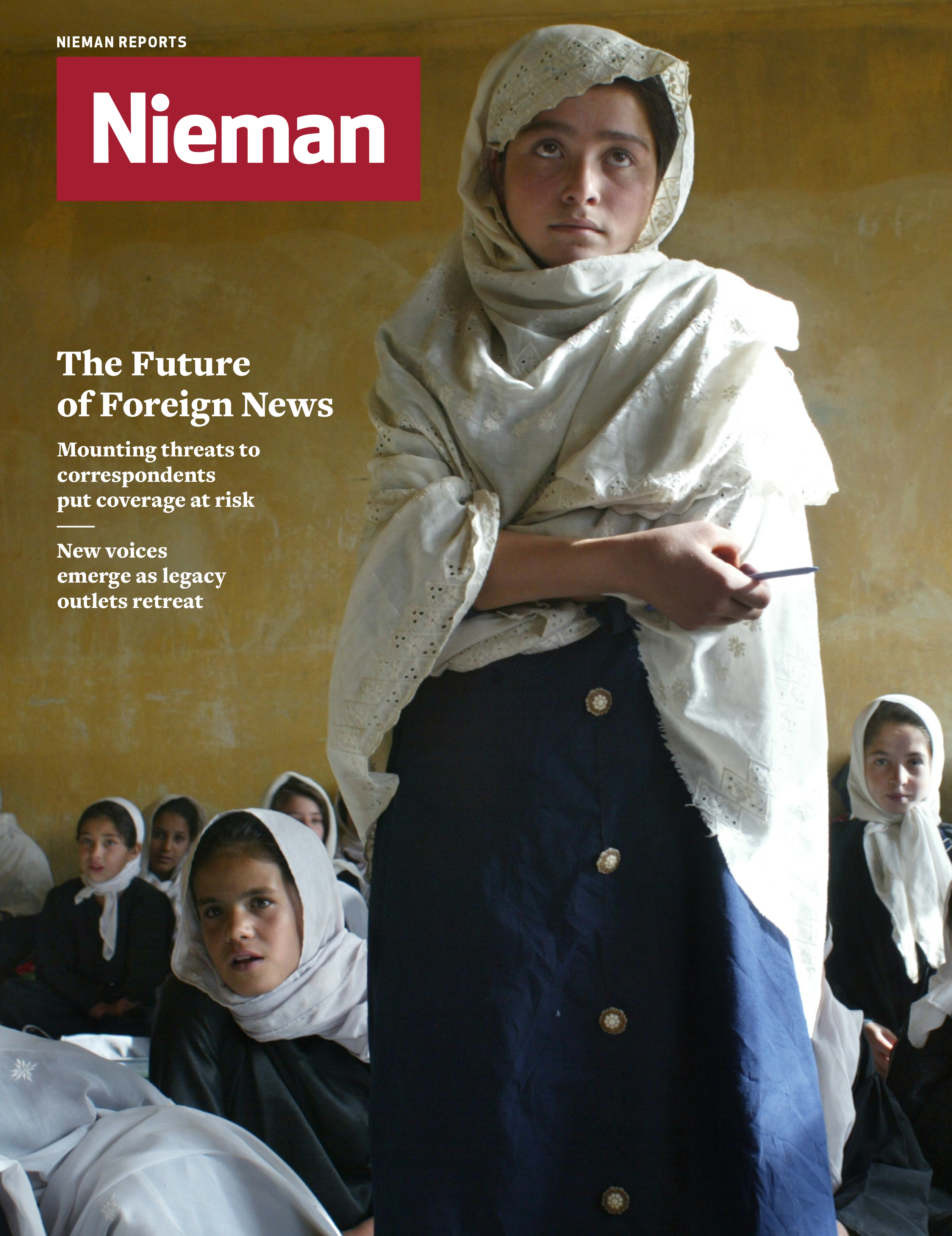

So, after deciding I didn’t want to live my life in this precarious and frustrating way, I adapted my coverage to photography and joined the U.N.’s communications department. I entered the organization in mid-2011, at a point of transition as it laboriously moved away from issuing press releases choked in formal language and started employing new multimedia techniques. With postings in Afghanistan, Libya and Iraq, the U.N. allows me to remain in this region’s most fascinating parts at transformative moments and over the kind of long periods that no editor or magazine could justify. I also have the chance to work on out-of-the-box projects, like the narrative documentary on Libya’s first free and nationwide elections in over 50 years, in which I followed five Libyans stepping forward to claim a role in the running of their country.

Within the U.N., UNICEF and U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) are transforming how they communicate by hiring top international photographers to document daily life in the world’s refugee camps. UNHCR’s Tracks website is a cutting-edge online storytelling venue employing video, photography and text to tell the stories of today’s anonymous global nomads. UNICEF’s No Lost Generation tells the stories of an entire generation of Syrian children at risk of being left behind.

My work has shifted from frontline journalism to aftermath reporting. While my scope for publicly speaking truth to power has shrunk, I can show how international crises affect the lives of ordinary people. Maintaining popular interest in shattered lives using emerging storytelling tools is hard but rewarding. And remarkably, the U.N.’s hiring managers appreciated my language skills and regional knowledge more than editors ever did. Working for the U.N. will never match living by my wits in the field, but I am once again part of a global newsgathering organization, just one a little different from what I’d expected.

Earlier this fall, an Iraqi woman swept up her tent during a sandstorm. She was one of the many displaced who had been living in the temporary Khanke camp.