But, in order to have a substantive discussion about newsrooms, race, and how we cover these stories, we in the media must turn the lens on ourselves and acknowledge our complicity in these tragedies.

It’s not an easy task. But it is a necessary one if we intend to be part of the solution, rather than the problem.

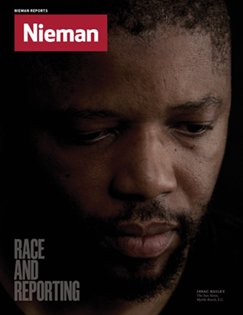

We have to ask ourselves: What role do we play in all of this when we constantly barrage our viewers and readers with images of black men as criminals? The repetition of these images has conditioned all of us (including police officers who carry weapons) in ways that make it difficult not to view black men and boys as dangerous.

In my hometown of Chicago, the number of homicides is about half of what it was in the early 1990s. But you wouldn’t know this by looking at the 10 o’clock news, which consistently leads with stories about violence and shootings, mostly in predominantly African-American and Hispanic neighborhoods.

The story of race is deeply rooted in fear. We media types play into that

I’m not saying these stories shouldn’t be covered. Only that they often lack context and depth and feed a perception that skews and even skewers reality. Complicating this further is that these stories often are at the top of the news not because “what bleeds leads,” but because a 24/7 news cycle requires editors to deliver something new.

I don’t believe the intent is always malicious. It’s just that the consequences are never benign.

But this isn’t only about black men being depicted as violent. We media types tend to cast blacks as the poster children for far too many of society’s ills. Not because it’s the truth, but because it fits the familiar trope and it’s convenient to think inside the box.

A 2012 study by the College of Wooster analyzed the images that ran with 474 poverty-related stories in Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News & World Report from 1992 to 2010. The study found that “while Hispanics are underrepresented in media portrayals of the poor, African-Americans are overrepresented.” Blacks appeared in 52 percent of the images, despite being a quarter of Americans living in poverty during that period. Although Hispanics made up 23 percent of the poor, we saw their faces in just under 14 percent of the photos.

If this were just about the media misrepresenting the poor that would be one problem. But it’s compounded by the harsh stereotypes that are attached to poor blacks, making it difficult for them to define themselves not only with journalists, but with educators, employers, and, yes, the police.

In 2008, one of the reasons I was excited about the prospect of a black family occupying the White House was that I hoped (however naively) that the image of the Obama family would serve as a counterweight to the many negative depictions of blacks. I also hoped that the media would no longer portray as anomalies successful black men who weren’t athletes or entertainers.

That really hasn’t happened.

The story of race in this country is one deeply rooted in fear—fear of the unknown, fear of the little known. We media types play into all of that, sometimes wittingly or unwittingly depending on the news outlet.

These stories and images are so powerful. They are also so unforgiving. They become hardwired into our brains. I would argue that the race problem in America is as neurological as it is sociological. Race makes us reactionary. We, pardon the cliché, shoot first and ask questions later.

For me, the reason it’s important to have a diverse newsroom and more in-depth news stories about race is because we need to train our brains to see people of color as individuals rather than types. It’s a huge undertaking, one we’ve struggled to achieve through the ages.

Still, if we journalists don’t move beyond the standard, knee-jerk narratives, we will do more harm than good. Although that is not the mission of any news organization, it certainly will be the result.

Read about strategies for creating inclusive newsrooms in our Race and Reporting cover package