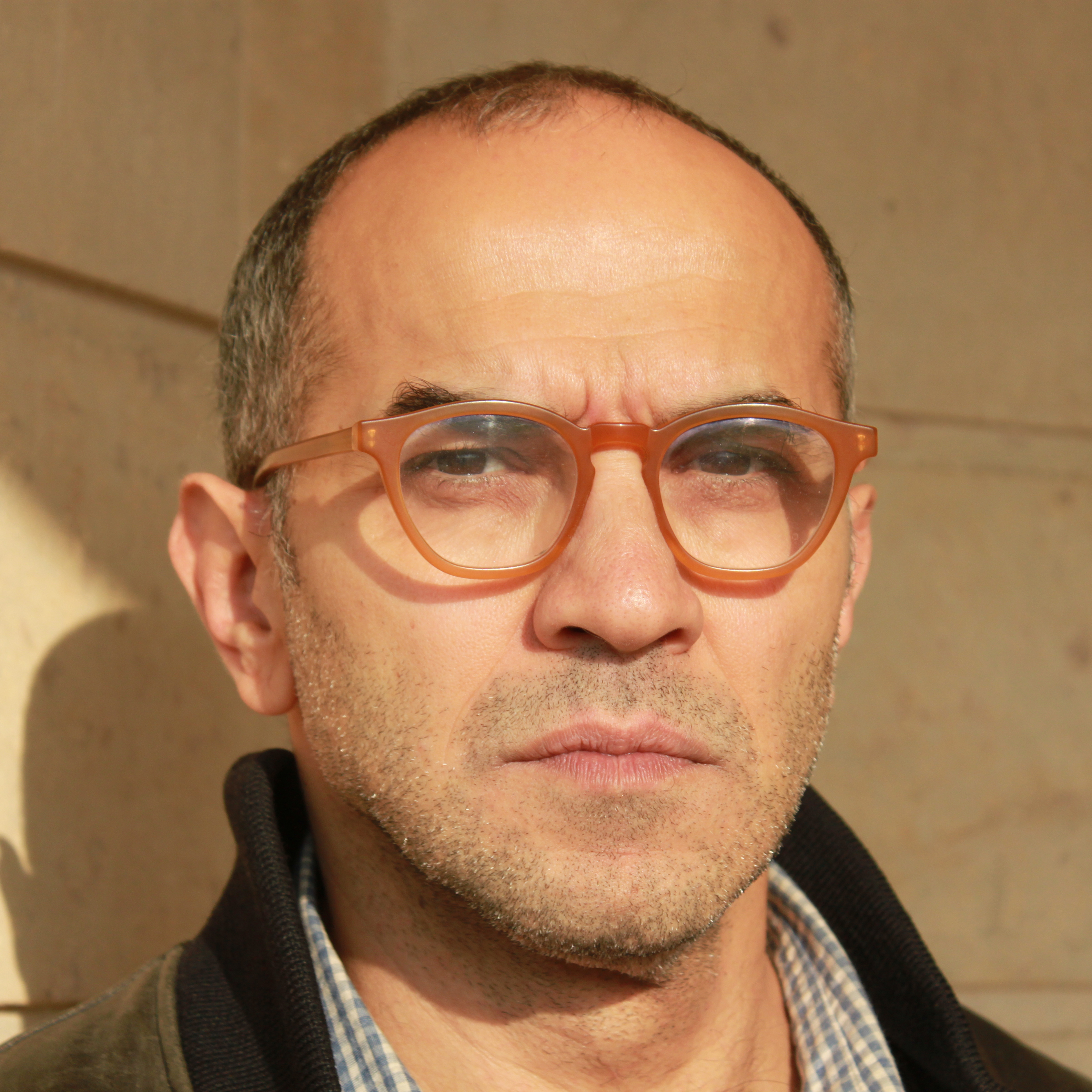

Protesters in Cairo last summer demand the release from prison of photographer Mahmoud Abou Zeid, known as Shawkan

Within minutes, social media was buzzing with calls for Saber to step down. Even the mainstream media joined in. Less than 24 hours after the interview aired, Saber resigned, an unprecedented outcome in a country where just a few years ago ministers were immune to public opinion and accustomed to remaining in office for decades.

On that same day Saber resigned, the first print run (about 48,000 copies) of the privately owned daily Al-Watan was pulped following an objection from “sovereign entities,” a common euphemism for the Egyptian Army or intelligence services, to a headline and a column. The headline—“7 Stronger than el-Sisi”—referred to the numerous challenges facing President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s efforts to reform Egypt’s Kafka-esque bureaucracy. The column, by Alaa al-Ghatrify, was a thinly veiled reproach of the president and those of his supporters who believe el-Sisi’s sagging popularity can be bolstered by sycophantic media coverage rather than concrete achievements.

The second edition of Al-Watan appeared later with a new headline—“7 Stronger than Reform”—and in the rest of the report, a sharp critique of the entrenched bureaucratic interests fighting to preserve the status quo. al-Ghatrify’s piece was gone, though it promptly appeared on his Facebook account and was widely shared.

These two incidents illustrate how far Egyptian media has come—and how far it still has to go—since the Tahrir Square protests of 2011 that toppled President Hosni Mubarak. Columnists and reporters are once again beginning to expose corruption, police brutality, and the failure of the state to provide basic services and uphold the rule of law. Social media storms can force ministerial resignations. Yet, when journalists go too far, censors are still quick to step in, as the al-Ghatrify case shows.

“The Egyptian media is still in transition,” says Naila Nabil Hamdy, associate professor of journalism and mass communication at the American University in Cairo, a transition from state-run to independent entities, from print to digital media, and from national to local coverage. Leading this shift is a cohort of digitally savvy journalists-turned-entrepreneurs launching their own platforms. Encouraged by post-Mubarak revolutionary fervor and fed up with the stifling environment of state and corporate media, these 20- and 30-something reporters face formidable obstacles: a restrictive legal system, the threat of government repression, and scarce venture capital willing to support independent media projects. The challenging political environment has forced these editors to innovate, developing ownership, business, and journalism models never seen before in Egypt.

The new voices are, however, still vastly outnumbered by state and corporate media. The state-run media empire alone is made up of newspapers (some 50 dailies and weeklies), radio stations, and TV networks that employ some 74,000 staff. State-controlled outlets have little or no credibility among Egyptians but remain on autopilot, with millions of dollars of government money keeping them afloat. On state-run TV news, nationalist songs are intercut with images of state officials in sharp suits and sunglasses next to President el-Sisi delivering a speech or inaugurating a new infrastructure project, followed by archival footage of flybys and elite military troops rappeling down walls. Editorial independence also is rare among private media firms, which require reporters to hew closely to political or corporate interests.

The political situation is also fraught. Since the overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013, the country has seen a considerable deterioration in its human rights record and a dramatic increase in the number of jailed activists and journalists. Egypt’s national union of journalists, the body that represents print media workers, accuses the police of escalating its attacks on journalists and arresting them on spurious charges. Between January and March of this year alone, the union documented 126 “violations” against journalists—verbal or physical abuse, confiscation of equipment, or prevention from covering certain events. A report by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) concluded in June that 18 journalists were “behind bars in relation for their reporting—the highest in the country since [CPJ] began recording data on imprisoned journalists in 1990.” The report describes prison conditions: “In letters from prison, some journalists wrote that they often do not see sunlight for weeks; others described the torture of prisoners, including the use of electric shocks.” The Egyptian government rejects the accusations, insisting that those in detention are being tried for other offenses.

The arrest and subsequent trial of the three Al-Jazeera journalists in December 2013 has thrown into sharp focus the plight of journalists in Egypt. After 400 days in jail on charges of broadcasting false news and supporting the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood, designated as a terrorist organization by the Egyptian government, Australian Al-Jazeera reporter Peter Greste was released in February. His two Egyptian colleagues, Mohamed Fahmy and Baher Mohamed, won an appeal and were released on bail. They await a verdict in their re-trial.

Al-Jazeera journalist Mohamed Fahmy stands accused of being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, deemed a terrorist organization by Egypt

Mada Masr is using that space to cover controversial subjects. In May of last year, the site published an in-depth account of the corruption case in which Mubarak and his sons were convicted of embezzling some $17 million in state funds to spend on their private homes; Mubarak was sentenced to three years imprisonment and his sons for four years each. Based on what the site described as “exclusive access to court documents” and the firsthand account of a key prosecution witness, the piece offered a rare insight into how corruption operated in the highest office in Egypt. Mubarak and his sons are appealing the verdict. Although most media outlets covered the case, none offered an account as crisp, thorough, and well documented as Mada Masr.

New outlet Mada Masr offers a depth of comment and analysis rare in Egyptian journalism

The site signed a deal in June with WikiLeaks that give it exclusive access to more than 100,000 documents from the Saudi Foreign Ministry. Mada Masr has published several pieces based on the documents, including one about the alleged role of members of the Saudi royal family in helping an Egyptian businessman wanted on corruption charges smuggle some of his possessions to Saudi Arabia. Another suggested that Cairo’s Al-Azhar mosque, the most influential seat of Sunni Islam, was being influenced by Wahhabi Islam, Saudi Arabia’s more puritanical strand of the faith, in that country’s sectarian conflict with Shia Iran. Rather than publishing the relevant documents with little or no context like other papers, Mada Masr contextualized the story, offering a depth of comment and analysis rare in Egyptian journalism.

Mada Masr describes itself as an independent and progressive content provider that is different from media in Egypt that are controlled by the state or corporate interests. Its coverage and news agenda reflect that ambition. In practice, Mada Masr becomes a platform for dissenting voices and a tool to challenge dominant narratives whether they are about the economy, political conflict, or even cultural discourse. Mada Masr thus treads a fine line between advocacy journalism and the impartial paradigm it claims to represent.

Mada Masr stands out in another respect: It is trying to bring maximum transparency to its operations. At the end of each year, staff publish, in Arabic and English, an audit of their editorial performance—what the site covered well and what it covered poorly, how journalists dealt with controversial issues and the risk to their safety. “We do the annual review to reflect on our practice and develop it,” says Dalia Rabie, one of the editors of the site. “We are a growing project, and we are constantly trying to learn from our failures and successes, and we also like to engage our readers in the process.”

Editorial success is one thing; commercial viability another. No local capital is available without strings attached, yet Atallah and other new digital outlets need investors to keep their sites going until other revenue streams come online. Mada Masr currently receives financial support from international media development organizations while it explores live events as a complement to revenue generated via advertising and subscriptions. One such event is Mada Marketplace, a combination craft fair and music festival on the old campus of the American University in central Cairo, a stone’s throw from Tahrir Square. Rock bands perform against a huge Mada Masr banner, while attendees browse food stalls, book stands, and tables heaped with artisan jewelry and handmade clothes. Mada Marketplace is “more of a community-building than money-generating activity,” says Amira Salah-Ahmed, its business development officer and co-founder. “It gets our audience to come out from behind the screens to meet us and meet each other and tell us about what we produce, stories we should cover.” Salah says that Mada Masr broke even on its first event; not bad for an organization still building its brand.

Though some Egyptian media are bolder in their reporting today, censors still routinely step in when they think journalists have gone too far

Welad El Balad is certainly different. Whereas almost all Egyptian media outlets are concentrated in Cairo, Farag has her eyes set on the largely uncovered countryside, where more than half of Egypt’s over 80 million people live. From an office in 6th of October, a satellite city south of Cairo, she manages Welad El Balad’s eight weekly publications, two of which are digital-only, spread over eight provinces in the Nile Delta and Upper Egypt. Some 100 journalists operate out of newsrooms situated in the communities they cover, reporting on hyperlocal issues—education quality, healthcare in public hospitals, clean drinking water, industrial waste dumping on farmland. Page two of each paper, called “We Are Listening to You,” is dedicated to complaints from readers and responses from local government. In the absence of elected assemblies, these forums are the closest readers are likely to get to local democracy.

While almost Egyptian media outlets are concentrated in Cairo, Welad El Balad focuses on the largely uncovered countryside

Welad El Balad is groundbreaking in a country where the media have always been Cairo-centric and owned by either the state or big money. And the approach seems to be catching on. Farag says that the 2014 circulation was 200,000 for all eight newspapers combined. Given that around five people read each copy, Welad El Balad reached around a million people. Sales and ad revenue now cover 25 percent of operational costs. For the rest, Farag relies on foreign aid, a risky strategy given the suspicion with which the West is regarded in Egypt. In May, for example, Welad El Balad had to issue a statement refuting comments in mainstream media suggesting that the company was receiving money from abroad as part of an international conspiracy to destabilize Egypt.

To survive, start-ups like Welad El Balad and Mada Masr have to come up with novel solutions for old problems: How to make money and reach readers. To ease dependence on donors, Welad El Balad offers media training for young journalists or bloggers, while Mada Masr publishes a daily e-mail newsletter that translates and analyzes Arabic-language newspapers in Egypt. Aimed at foreign diplomats and expats, individual subscriptions are $50 per month. Welad El Balad relies on citizen journalists for much of its coverage and, in another first for Egypt, deploys informal distribution networks that comprise contributors, volunteers, small business owners, and even itinerant vendors. The papers sell for around 13 cents, and distributors get 25%. Some local editions, like Al-Fayoumiya, based some 130 kilometers southwest of Cairo, also host cultural activities several times a month, including readings, book signings, and debates. In recognition of Welad El Balad’s work with underserved communities, the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN IFRA) gave it a Silver Award for the best community service in April.

An Egyptian denounces toppled President Hosni Mubarak against the backdrop of two journalists who were killed during the uprising in 2011

In Cairo, where some neighborhoods have over 1 million residents, a local paper takes root

Launched two years ago, the first Mantiqti covers downtown Cairo, an area that emerged outside the medieval Islamic city some 150 years ago. Designed to be “Paris on the Nile,” it has fallen on hard times but still retains an air of faded glory. Mantiqti has its office on the ground floor of a block of flats that miraculously survived the onslaught of modernization. It still has high ceilings, wooden shutters, and colorful floor tiles. Atia’s colleagues stuff advertising leaflets into the latest issue as he explains why Egypt needs hyperlocal journalism. “National newspapers are only interested in the area when there is a big event, but then it is forgotten,” he complains, citing the issue of street vendors in central Cairo as a case in point.

Covered only sporadically by the national media, so many street vendors had set up shop in the area that local residents complained that there was no room for pedestrians. Mantiqti covered the issue intensely. “We gave a platform for everybody’s grievances,” Atia says. “We did not take sides. The only side we took was, How do we help transform this chaotic situation into a much more healthy environment for everybody?” Atia is convinced that the paper’s coverage played a part in finding an innovative solution. The street vendors were moved to a specially designated market zone, thus easing congestion on neighborhood sidewalks.

Mantiqti comes out monthly and has a circulation of around 10,000 copies. Atia hopes to break even by the end of 2016. He’s now looking for investment that will enable him to launch new Mantiqtis in other, more affluent parts of Cairo and move from monthly to weekly publication. Then he hopes to attract national advertisers lured by the more upscale demographic. In the meantime, he’s developing digital portals for specific neighborhoods and a mobile app enabling users to rate local businesses and services. His company, too, organizes events and runs media training courses, covering topics like basic video journalism and journalistic ethics.

Purging Egyptian journalism of the legacy of 60 years of authoritarian rule will take many years. But Atia speaks for many of his entrepreneurial colleagues when he says, “We have to be part of the process that puts these issues on the agenda—media development, press freedom, professionalism in media production. I’m definitely not waiting for those [things] to happen. I am actually part of the process that is making those things happen.”