India now has the third highest number of Internet users in the world—behind the U.S. and China

In the evenings, they watch one of the major Indian news channels, whichever has the most interesting stories or the least irritating shouting match, and often switch to the BBC or Al Jazeera. I stay with them once or twice a year when visiting India, and we often discuss news and current affairs over an evening drink. In India—unlike in the U.S.—TV and print are still doing very well, as suggested by the Singhs.

The couple represent the opportunity—and one of the challenges—facing American news outlets looking to set up shop in India. Over the past year or so, Quartz, BuzzFeed, and The Huffington Post, as well as Business Insider, have all launched India-specific versions of their sites, each chasing the same 125 million fluent English speakers. At the same time, legacy brands have a diminished presence. CNN is ending its content and licensing partnership in the country, and The New York Times scrapped its India Ink blog last year.

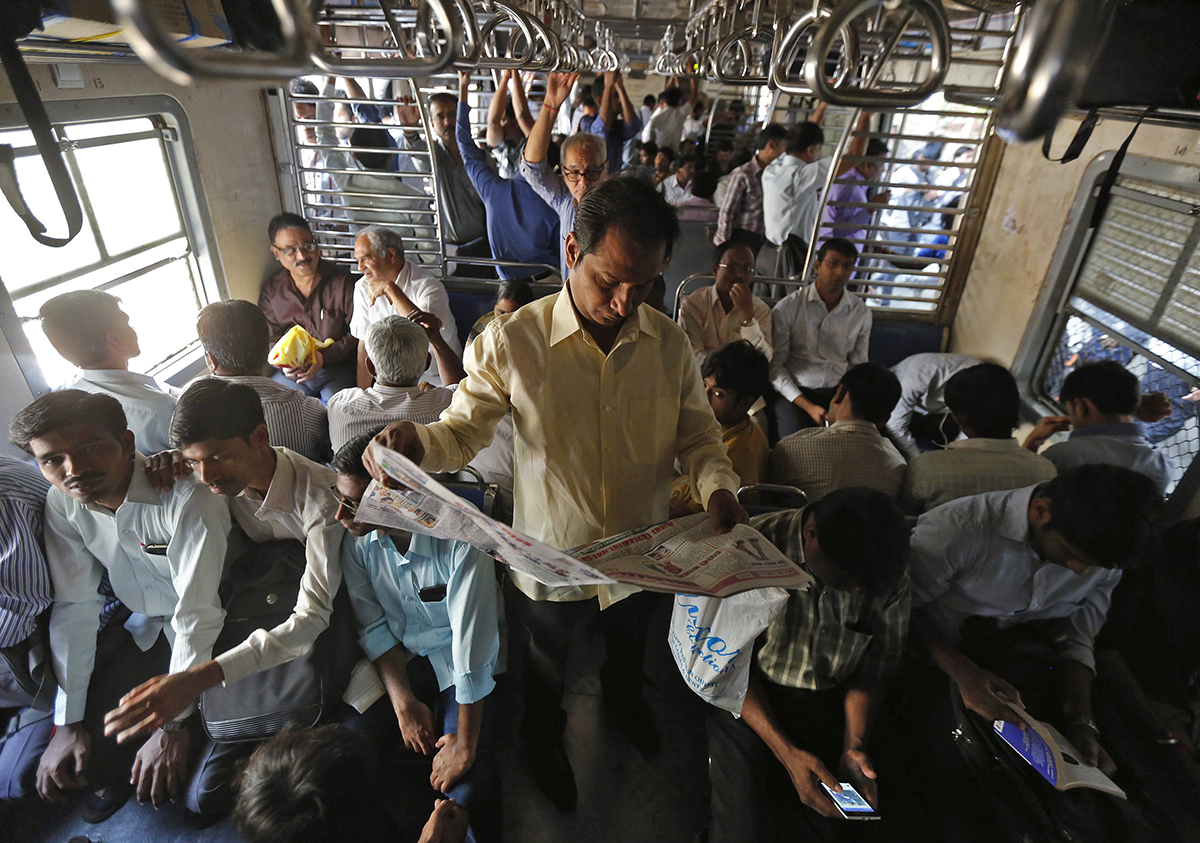

The recent digital arrivals face considerable revenue challenges. Although Internet use is growing—India now has the third-largest number of Internet users in the world, behind the U.S. and China—advertisers spent only about 12 percent of their budgets on digital in 2014. In the U.S., it’s closer to 30 percent. Plus, for most of the population, broadband networks are poor to nonexistent, and cellular coverage is erratic at best. Furthermore, many Indians still prefer to consume news through legacy channels. The challenge: How to make money with minimal staffing and a strategy based almost exclusively around digital advertising and branded content, when print and TV are still so dominant.

Meanwhile, many of the billion-plus Indians who have had no Internet access at all are expected to buy inexpensive smartphones. Though these people are linguistically and culturally diverse, they will likely share three characteristics: Their devices will be basic; their literacy rates will vary widely; and the vast majority won’t speak English. “We’re on the verge of seeing a massive number of people discover the Web for the first time, mostly through mobile devices,” says the BBC World Service’s Indian-born mobile editor Trushar Barot. This emerging demographic represents the next big audience for news.

Cheap smartphones threaten to end the hegemony of print media and TV in India

In rural India, literacy is shockingly low: According to the government’s Socio Economic and Caste Census in 2011, the most recent year for which data are available, 315 million people living outside cities are illiterate. Nevertheless, there is an opportunity here.

Indians read newspapers and watch TV news in numbers that can still surprise media executives in the developed world. According to the 2014 Indian Readership Survey, about 300 million people, around a quarter of the total population, read a print paper. The largest daily, the Hindi-language Dainik Jagran, had a readership of 16.6 million that year; the biggest English paper was The Times of India, with a readership of 7.6 million. By comparison, the biggest paper in the United States, USA Today, has a combined print-digital readership of just over 6.7 million, according to the most recent data from the Alliance of Audited Media. Oh, and overall newspaper circulation in India is rising.

India now broadcasts more than 400 news and current affairs TV channels. The Hindi-language Aaj Tak news channel has nearly 40 million weekly viewers, according to India’s Broadcast Audience Research Council. The biggest channel overall, the entertainment-focused Star Plus, has a weekly audience of about 400 million. In India, “TV is already at scale and is going to grow,” says Samir Patil, the Mumbai-based founder of digital news site Scroll.

Despite the continuing strength of print and TV, there are nonetheless reasons for legacy media to fear the encroachment of digital, according to research compiled by Samar Halarnkar, editor of the nonprofit data journalism site IndiaSpend. Even as India’s overall media revenue pie expands, print’s share is falling, mostly nibbled away by digital. And despite ongoing circulation growth, more than 70 percent of the industry’s ad revenue originates from just two cities, Delhi and Mumbai, where the combined population is around 50 million and smartphones are becoming ubiquitous. Once Delhi and Mumbai advertising dollars start shifting to mobile, papers may start facing problems.

Anticipation of that shift is part of what brought Quartz, BuzzFeed, and The Huffiington Post to India. Their editorial strategies differ—BuzzFeed fixates on viral pop culture content before planning to ramp up to serious news; Quartz focuses on business and financial briefs; The Huffington Post sports a broad mix of repackaged and original content—but their commercial challenges are identical.

Quartz India, which has six local journalists working out of a small Delhi newsroom, says traffic has increased from 200,000 monthly unique users to around 1.5 million over the past year. Not all of these users will be in India itself, with a large diaspora accounting for at least some of the growth. Quartz India content is aimed at both an Indian and a global business audience, with articles on everything from Bangalore real estate to Google’s hiring strategy in Hyderabad. “That approach is harder in some ways,” says Quartz publisher Jay Lauf, “but we think focusing on what’s truly interesting about a topic allows you to attract a readership on both levels. Our audience target is the same business leaders who we find read our regular Quartz content.” Lauf describes Quartz India’s advertising performance as “wildly successful,” particularly among big global brands like GE, though he declined to cite specific numbers.

BuzzFeed India editor Rega Jha, who runs a team of six from a small office in Mumbai, is replicating the same editorial strategy that has worked so well in the U.S.: Focus first on humor and pop culture, then gradually add more substantive journalism. “The plan down the line,” she says, “is to hire a news team to really aggressively cover the kinds of stories I don’t think the mainstream organizations here are doing justice.” Jha won’t say how big BuzzFeed’s audience is but she hopes to build it—and, eventually, its revenue streams—with distinctive coverage of progressive social justice issues like sexuality and feminism, still fringe topics for much of India’s media but of increasing interest to younger, urban Indians. More than half of the country’s 1.2 billion population is under the age of 25, including Jha herself.

Some are skeptical about the effectiveness of simply building a big audience and hoping advertisers will come. “The idea of scale and reach as the key metrics is incredibly seductive and somewhat dangerous when it comes to news,” says Harvard Business School professor Bharat N. Anand, who researches the media and entertainment industries. Anand thinks subscriptions or paywalls—or some combination thereof—are essential to sustainability. But to convince Indian audiences to actually pay for content, when newspapers still cost only a few cents, he believes media companies must create high-quality, unique user experiences. Digital news outlets will need deep pockets and patience.

Print newspapers in India have surprisingly high circulations, and readership is on the rise

Entertainment is there—movies, music, instant messaging. As for information, Kundan reads newspapers and watches TV because it’s much easier and cheaper than using up his precious data allowance on news platforms not designed for him and not in languages he can read. To that end, I am working on a project, funded by the Knight Foundation, to build a platform that makes news and other essential information much more accessible through these types of inexpensive handsets.

Ketla—which means “how much” or “how many” in Gujarati, my family’s native language—uses swipe-able comics to convey news and other information to non-English speakers of differing literacy levels. Initially, Ketla will produce one locally relevant news story a day, with artists and editors using information already in the public domain to create simple comic strip narratives.

There are other uses for Ketla, too. A local healthcare provider, for example, might want to publicize a free service for pregnant women and explain why it’s important. Ketla could help the provider create and distribute a digital comic strip for that purpose. Because the platform uses illustrations, not video, the data is light enough to work across India’s erratic networks. Text is minimal, so it can be easily translated to any of India’s officially recognized languages. Plus, the content is shareable via existing social media platforms like WhatsApp, which helps further extend its reach.

Multilingualism is essential for reaching rural audiences in India, which has, in addition to about 20 official tongues, hundreds of dialects. “It’s a huge challenge for any platform to service a country as linguistically and geographically diverse as India,” says Raheel Khursheed, a former TV reporter who is now head of news, politics, and government at Twitter India. Twitter thinks it’s worth trying to meet that challenge because it believes platforms that operate exclusively in English have limited room for growth. Indian Twitter users can tweet in any language available on a given mobile device, and the company is also working with regional newsrooms to help them craft stories more native to the social Web.

Translation software is making it easier to reach audiences. The Google Translate app now includes Hindi as one of its languages. With its “real-time visual translation,” you can point your phone at a foreign menu or road sign and find out instantly what it says. Handsets from Micromax, maker of some of India’s best-selling smartphones, feature a new, locally designed operating system that enables real-time transliteration and translation. So, a message typed in English can be received in Hindi; one written in Gujarati (which is spoken by about 50 million people, according to the 2001 census) can be received in Punjabi (about 30 million speakers). “For the 90 percent of Indians who don’t use English, we saw a clear opportunity,” says Rakesh Deshmukh, CEO of MoFirst, the firm that makes the operating system.

For digital news, this technology could be a game changer. If the software can be made to work to a publishable standard, and not just with informal private messages, where a degree of error is usually tolerated, news outlets could save a lot of time and money on translation and transliteration. Crucially, audiences could also control the language in which they receive news. Digital news content would suddenly have a much bigger reach.

Journalistic efforts are already under way to create this kind of content. The People’s Archive of Rural India, a network of volunteer journalists covering stories they say mainstream urban media overlook, aims to record the lives of the more than 800 million Indians who don’t live in cities—in every possible language and various digital formats. The project, still in its early stages, is also dedicated to archiving India’s languages.

In Delhi, the Singhs may be settled in their media routine. But news outlets should consider paying closer attention to Kumar and other Indians like him, who represent an enormous emerging market eager for news, information, and entertainment. I can think of a billion reasons why it’s in the interests of news outlets to overcome barriers of language, literacy, and relatively low-end tech.