Audience engagement is a phrase that comes up often in conversations about the news industry, but how to achieve it is not always so clear.

In a recently released American Press Institute report, Monica Guzman offers practical guidance on how, by boosting engagement, newsrooms and independent journalists can grow their audiences, heighten their impact, and even find new sources of revenue. Through collaboration, she writes, journalists can not only promote their work, but improve it. Audiences can fill many roles: collaborators, contributors, advisors, partners, and advocates. “Collaboration is not about what your audience can do for you,” Guzman says, “but what you can do with your audience.”

For the study, Guzman talked to 25 news leaders and innovators across mediums—from news organizations local and national, large and small, for-profits and nonprofits—to scope out the best practices in audience and community engagement. Here are a few of her conclusions on how journalists can better engage their audiences:

Participate in the exchange

Perhaps the simplest and most important thing a journalist can do to strengthen online conversation is just to show up.

A study of 2,500 political comments on 70 political posts by a local TV station showed that when a reporter jumped into a comment thread, uncivil comments declined by 15 percent (though, importantly, when the TV station’s own branded account jumped in, there was no effect). It’s difficult to say for sure why this happens, but many leading journalists offer the same explanation: People speak more thoughtfully when they know someone is listening.

“They’re so used to showing up on these pages and nobody’s paying any attention,” said Connie Schultz, a syndicated Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist who’s built an unusually engaged community of tens of thousands on Facebook.

When you show your public that you are listening to what they tell you, you encourage greater participation. But once you “show up” to a public exchange around your work, what do you do? We’re going to talk about three possibilities. Think of them as the beginner, intermediate and advanced ways to strengthen interaction by participating in public conversations:

- Respond

- Encourage

- Guide

Respond

Not all journalists have the time or inclination to talk deeply with the public. But there is one small step all journalists can take to support the public exchanges their work inspires. That is to respond to relevant questions. It takes little time, it is simple to do, and it does much to strengthen the quality of public interaction.

When you respond to valid reader questions publicly, you help clear up misunderstandings others in your audience might have. You also send the message that you care about how well your audience understands what you’re sharing with them.

In a set of internal guidelines from 2015, Chalkbeat suggested that its staff “should always try to respond to questions that readers ask in the comments section” of their stories.

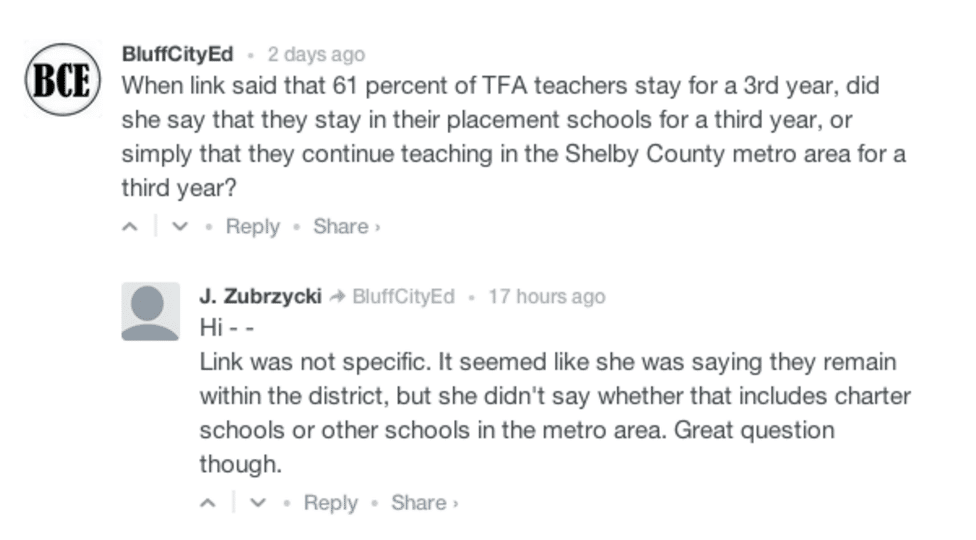

Below is an example from Chalkbeat’s Tennessee bureau. Note the word of praise at the end of reporter Jackie Zubrzycki’s response to the reader’s question about something a district development specialist had said:

Even when they don’t pose direct questions, comments can show you what readers remain curious about and where you can provide more information. Chalkbeat New York reporter Geoff Decker updated his story after reading one such comment:

How do you know what questions constitute serious readers questions, and are therefore worth a response? Telling the difference can be tough. Some valid reader questions are communicated with a sense of anger or urgency. Other times, reader questions seem meant to express cynicism or to provoke a personal response rather than to engage honestly in debate or discussion. These questions can distract from a good conversation. Responding to them may further that distraction.

To ward off toxic comments and unproductive conversation (more on that later), it can be helpful to be the first to speak. Investigative reporters at The Desert Sun in Palm Springs, California, have at times left the first comment on the newspaper’s Facebook posts about their stories — just a quick hello to let others know they’re there. This encourages good discussion, Gannett social media leaders say, by providing readers with a human face with whom to interact.

Encourage

Another step journalists can take to strengthen public interactions around their work is to highlight strong contributions as models for others to follow.

There are several ways journalists can elevate strong contributions in whatever spaces people are talking. The key is to do it visibly, so the contributor feels appreciated and others can see and model the behavior.

With a minimal time commitment, you can:

- Thank: Thank contributors for their productive comments. This is as easy as a reply to a comment on a forum (“Thank you for your thoughtful response”) or an upvote on a forum that includes that feature. Even a “like” on Facebook communicates some gratitude.

- Elevate: Place a strong comment somewhere prominent in your story or website, to both reward the contributor and give others a model to follow. You might consider updating the story to include the comment as a way of encouraging others to join the conversation through a specific angle.

- Share: Re-distribute the model comment in the channels where you hope to reach more contributors. If the comment is a tweet on Twitter, for example, you could simply retweet it to your followers, ideally with your own comment explaining its value to the story or project. If you’re blogging, you might create a whole post or section of a post to feature and reflect on the comment.

To highlight its readers’ contributions, The New York Times recently launched a “Best Comments of the Week” feature in which it rounds up the most insightful reader reflections from across its channels and notes their popularity. “His comment received more than 900 reader recommendations and attracted over 100 replies,” Times community staffers wrote about a comment by “Glenn in Los Angeles.”

As with any social gesture, the more effort you put into your interaction with your public, the more significance your words will have. With a little more investment in time, you can encourage strong contributions from the community you engage in a familiar but powerful way — by asking questions.

Journalists don’t always think of people who speak out on forums or on social media as sources, but that is precisely what each of them can be. If someone expresses something interesting and therefore shows a willingness to engage with a topic, respond to her publicly and ask her to elaborate. Essentially: interview the people who are showing you they want to talk.

A woman named Katherine Johnson mentioned on Connie Schultz’s Facebook thread that her 88-year-old aunt, Lois Mickey Nash, was going to march in protest of a decision to absolve a white Cleveland police officer in the shooting deaths of two unarmed civilians who were black. Schultz asked Johnson for more information, interviewed Nash for two hours in her living room, and made her the subject of one of her columns.

It is natural for journalists to feel anxious about the mean, angry or otherwise disruptive public contributions they may receive. By encouraging good contributions — either by highlighting or engaging with them — journalists also discourage bad ones. This cold shoulder approach does not deliver results as immediately as banning users and deleting comments, news leaders admitted. But the more you and your well meaning contributors can turn toward each other, the less disruptive those angry voices become.

Guide

A powerful way journalists can strengthen the quality of public interaction is by adopting the role of a full-fledged moderator. This means doing what we discussed above — and more — to make the conversations you spark around your work as valuable to their participants as possible.

Moderating conversations around your work is a big commitment that can bring big rewards. The more people get out of the conversations you spark, the more they’ll want to come back, deepen their participation, and cultivate their connections with you and each other. The result is a slow but steady accumulation of trust, loyalty and mutual support. Over time, the contributors you gather become a community that cares about your work, largely because you’ve shown them it’s their work, too.

One of the most beneficial things journalists earn from a community, as opposed to an occasionally engaged audience, is the privilege of getting strong contributions even when we don’t ask for them.

The more people get out of the conversations you spark, the more they’ll want to come back, deepen their participation, and cultivate their connections with you and each other

“The good thing about building a community is that people will let you know what’s going on,” Connie Schultz said. “You’re building a real source book. Long ago I lost count of how many times that’s helped give me an idea of something to write about.”

I have argued before that at a time when anyone can participate in newsgathering, cultivating strong self-informing communities around key interests or values is itself an act of journalism. 1 Some hold that much of this work should be delegated to newsroom staff skilled in community engagement and moderation. Others argue that some aspects of community building should be a new bullet point in the job descriptions of all journalists.

There’s one rule of thumb regarding engagement about which leading journalists seem to agree: Journalists should engage in conversations with the public only to the extent that we are able to manage what we spark. Engagement efforts work best when they show that we value contributors and their contributions. If we spark an important conversation, it says a lot if we strive to make it great.

Schultz spends hours keeping her conversations on Facebook civil and productive. The loyalty of her community easily translates into high readership for her stories. Stephanie Schwartz, audience development editor at National Memo, said that when Schultz shares her syndicated columns published on nationalmemo.com with her Facebook community, traffic to the site picks up significantly.

Enforce civility

Online, an otherwise interesting discussion can easily devolve into a pointless war of words. Beyond encouraging civility in the ways we discussed above, there are at least three other things you can do to help keep conversations productive, journalists who moderate discussions said.

One is to enforce a civil tone. The second is to model it. And the third is to provide a gateway: give your community easy ways to practice being civil, so they’re more likely to do it even when it’s hard.

Let’s look first at influencing tone through policing or enforcement. This means deleting comments or banning users who inappropriately distract or otherwise disrupt the conversation. Some journalists are able to do this on their websites’ comment threads. Others depend on their colleagues to take these steps for them. Many newsrooms rely on technical features in their comments sections to help keep the peace, such as a flagging system, upvotes and downvotes, and threaded conversations. All journalists are able to control who speaks and who doesn’t on the conversational spaces they own, such as their Facebook pages.

But people also told me that unjustified enforcement can invite a community’s anger and erode trust. For that reason, if you enforce certain standards in the conversations you host, you should set out specific policies that will guide your decisions, remind people of them on a regular basis, and stay consistent in how you enforce them.

Model civility

A more enduring way to cultivate a desired tone is to set it by example, modeling the voice and approach you want others to use.

Strong contributions to public conversations tend to share certain characteristics. They stay on-topic. They build off each other. They don’t get personal. And they’re generous, adding real value to the group by contributing new perspectives or new knowledge.

An obvious place to set a civil tone is at the start of a conversation, when you pose a question or broach a topic. A more powerful place to do it, however, is in the conversation itself, where you can model the best ways to respond to and build off people’s contributions.

Conversations with engaged journalists yielded some concrete tips on how best to build off contributions in a public discussion.

First, identify a contribution that strikes you as valuable to the discussion. Then, compose a reply to it that uses it as a launching pad to advance the group’s thinking in a good direction. Reflect on the comment’s significance to the larger story or topic. Call out any new angles or questions the contribution opens up. Where possible, address these new angles or questions: add whatever extra knowledge you bring as a journalist.

In doing this you accomplish several things at once: You flag the comment as particularly valuable. You add to the group’s store of knowledge. Most importantly, you encourage contributors to express their own curiosity and to help each other out.

For a strong example of how even beat reporters can model strong interaction, see this comment thread from The West Seattle Blog, a neighborhood news organization in Seattle. Editor Tracy Record, who replies in the thread as “WSB,” responds 14 times, reflecting on readers’ observations and adding her perspective to build the group’s understanding of a developing crime story.

Practice civility

Journalists who cover the news might find it silly or counterproductive to ever talk with the public about anything other than the news. But when you aim to build community by moderating strong discussions in spaces where you and the public interact freely, it can make sense to pepper heavy topics with lighter ones that bring people together.

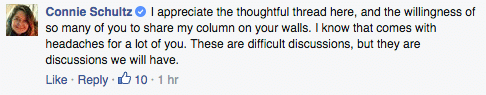

Connie Schultz deals with many contentious issues in her reporting and on her Facebook page. She manages to moderate productive conversations with her diverse Facebook community over topics like race, same-sex marriage and criminal justice. She encourages her community to stick with tough debates, as she did when an April 2016 column criticizing the chief of the Cleveland Police Union stirred up tensions on Facebook:

In between these serious discussions, though, Schultz invites people to join her in occasional light-hearted reflections. In one popular post, she invited people to simply share what was on their minds. In another, Schultz reflected on a photo of her dog, Franklin, when he was young, and invited her community to post their own pet pictures.

The purpose of these posts is not to distract contributors from serious issues, Schultz implied, but to help them build the camaraderie it takes to tackle those issues productively. These prompts get people to be friendly with each other, regardless of their views, and make it easy for everyone to contribute. In effect, mixing easy conversations with tough ones gets people to practice both being civil and contributing to discussions you convene. Those are handy habits for your community to have when you present them with more challenging topics.

“You’re trying to close the distance between you and your readers,” Schultz said. “How do you remind people that we have more in common than people think, regardless of our worldviews?”

Getting personal and responding to criticism

To many journalists, public engagement seems risky if they work to project neutrality on their beat. They can rest assured: Sharing your personal views, perspectives or experience is by no means a requirement for strong engagement.

Many engaged journalists strike a balance that is comfortable for them, sharing just enough of themselves with the public to ground a good conversation, but not so much that they alienate people, compromise their ability to report their beats or invite unwanted attention.

Engaging more frequently with the public exposes journalists to more criticism — some of it fair, some of it vicious. Telling the difference between what to take to heart and what to push away is never easy, engaged journalists told me, though the distinctions get crisper with time and practice.

When responding to fair public criticism, it helps to keep in mind that your goal in interacting with the public is always to advance people’s understanding — including your own

When responding to fair public criticism, it helps to keep in mind that your goal in interacting with the public is always to advance people’s understanding — including your own. If the person who has publicly criticized you has a point, even a small one, it’s good to say so, and be grateful for the help.

Most angry, personal posts are best deleted or ignored. But the emotional and psychological toll that persistently toxic conversations can take on journalists and vulnerable story subjects should factor heavily into newsroom decisions about how to manage this work.

Some newsrooms do not allow comments on stories about charged topics. Others, like Re/code, Reuters, The Daily Beast and The Toronto Star have shut down comments on all their stories, preferring to engage readers on social media. Whatever the strategy, managers would do well to take on moderation work wisely, assign it responsibly, and ensure that staff have the support they need.

Excerpted from Guzman’s American Press Institute report “The best ways to build audience by listening to and engaging your community.” Read the full report here.