In a series of anti-segregation editorials, Ashmore criticized Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus for his unwarranted interference in the confrontation over the admission of black students to a Little Rock high school in 1957.

In his lengthy telegram to President Eisenhower asking for understanding and support, Governor Faubus said among other things that he had not had his “day in court” to explain why his fear of possible violence was so great that he had decided to call out the National Guard to prevent integration at Central High School.We believe that the governor should have such a day—and that it should be in federal court as soon as possible.

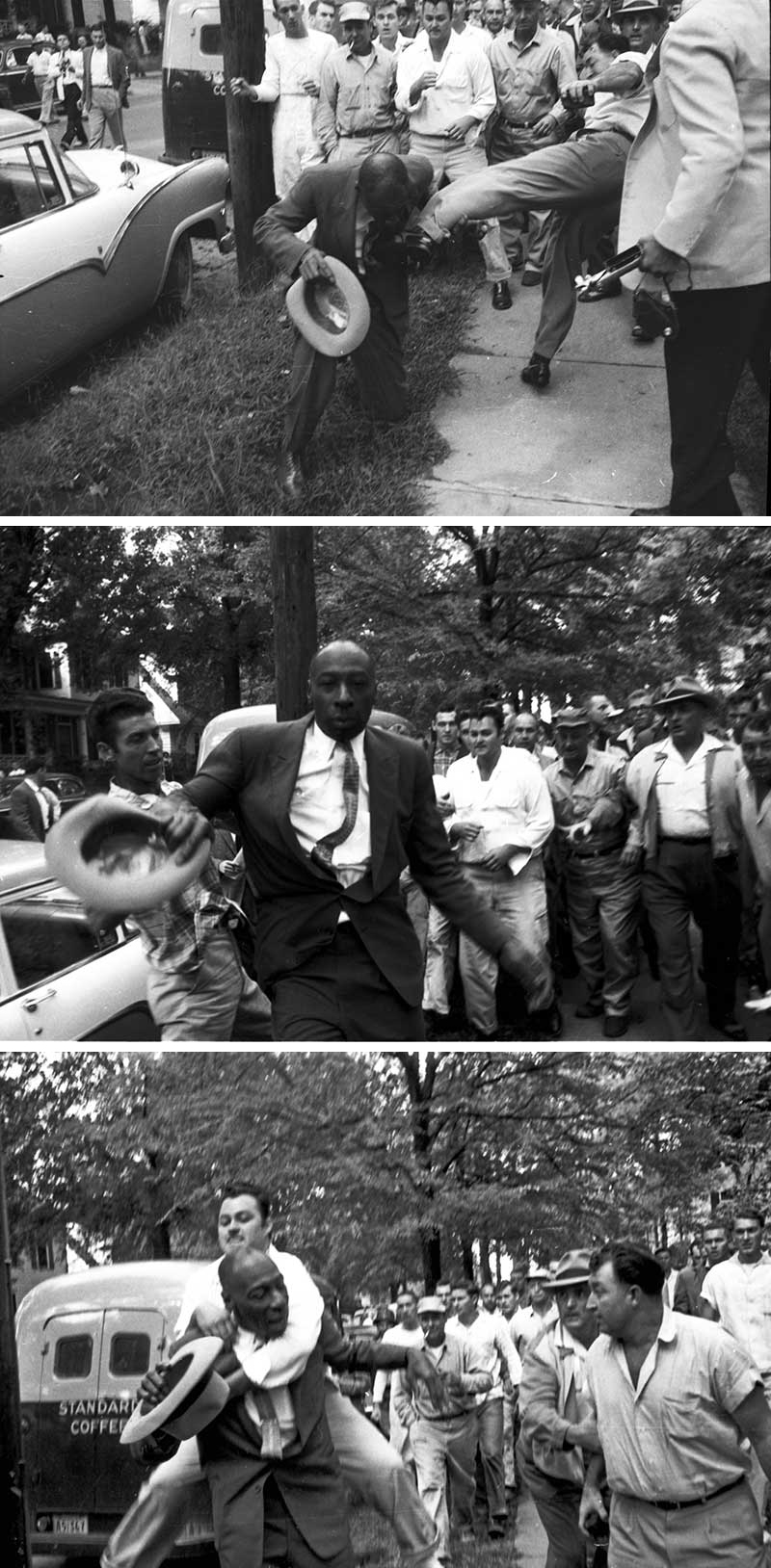

An angry mob assaults L. Alex Wilson, editor of the Memphis-based weekly The Tri-State Defender, in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957

There is, as it happens, a clear precedent. In a Texas case in 1932 the governor of that state called out the militia on the ground that the effort to enforce a federal law limiting oil production would produce violence. In a unanimous opinion written by Chief Justice Hughes, the Supreme Court rejected two basic contentions of the Texas officials— first that the governor was personally beyond the jurisdiction of the federal courts, and second that the reason for his calling out the militia was not a proper matter for the court to consider. The Supreme Court held that the reverse was true in both instances—that the governor was subject to injunction in any constitutional matter and that his action in calling out the Guard to prevent violence where none yet existed was really the heart

of the matter.

And the Court significantly noted further that in any event the only proper purpose for calling out the militia was to enforce the law, not to prevent its enforcement.

These are precisely the questions Governor Faubus has posed in the present case. Here as in the Texas action the heart of the matter is whether in fact the threat of violence was so real that Mr. Faubus was justified in preventing by force of arms the carrying out of a federal court order.

It is a question that must be settled if the impasse is to be resolved.

We hope, therefore, that Mr. Faubus is prepared to accept his “day in court” if it is offered to him, and in the act of accepting also indicate his willingness to abide by the court’s final decision.

If he refuses the only assumption will be that he is embarked upon a course deliberately designed to test the powers of his state office against those of the federal government. Having used force himself he would thus invite the federal government to reply in kind—with consequences that defy the imagination.