A member of the media walks near a monitor displaying election coverage during preparations for Trump's election night rally in New York

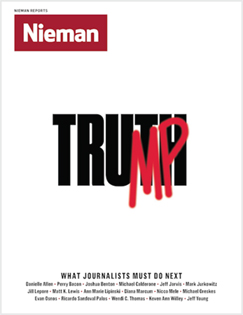

President-elect Donald Trump’s recent victory stunned a lot of Americans, not the least of which were members of the elite media, who couldn’t fathom the possibility that A) the so-called experts had been wrong, and B) the American public might actually want this vulgarian to be president. This seemed to me to be an appropriate time to revisit the constant problem of media bias.

As I personally seek to grapple with my own failures this election season—as well as my own place in the world of journalism (it’s healthy for everyone to be introspective and to perform a regular career audit)—I have been asking myself some serious questions.

With apologies to those who might prefer a more straightforward (traditionally structured) piece, what follows is a transcript of my internal dialogue (in Q&A form). I hope you find it enlightening:

Is media bias real?

Yes, and we can now see it more clearly than ever. Twitter is where journalists let their guard down and talk freely to one another. Frequently, this platform reveals the biases harbored by so many ostensibly mainstream journalists.

Let’s be honest: It’s no secret that most journalists skew leftward. I don’t believe the media has a grand conspiracy to elect Democratic politicians. The desire for ratings, clicks, and buzz are our driving force, but most journalists I know just happen to have a liberal worldview. They don’t set out to bias their stories in a secular or cosmopolitan way; it just works out that way.

So the problem is more cultural than partisan?

Absolutely. As it has often been said (perhaps most famously by Andrew Breitbart), culture is upstream from politics. Most political journalists are based in New York City or Washington, D.C.—not Omaha or Topeka. Few of them regularly attend some sort of worship service. Truth be told, their geographical location is just as telling and predictive as any political registration or history of activism—although it’s fair to note that many prominent journalists do have a history of having been a Democratic activist or operative.

As a center-right commentator, what kinds of bias have you personally confronted?

Subtle bias is the hardest to detect or combat—but it can be as simple as the way someone is introduced on a show or the way the chyron identifies them. It’s not uncommon to hear a liberal commentator identified simply as, say, “a columnist for New York magazine,” while their interlocutor might be called “a conservative columnist” from outlet XYZ. This is a signal to viewers suggesting that the liberal pundit is completely unbiased, while the conservative-leaning journalist has an agenda.

Does this bias impact your career opportunities?

I’d like to say that the adversity causes us to raise our game, but there’s definitely a double standard. Liberal journalists can suggest radical hypotheses (the case for reparations, the idea that “There is no such thing as a good Trump voter,” the idea that anyone who voted against Hillary Clinton is a misogynist) and essentially not be penalized for holding such fringe views. Indeed, many of these liberal opinion journalists work at (or will end up being recruited by) prestigious outlets, and they will likely be welcomed on the Sunday morning shows. A conservative opinion journalist who said something equally outrageous would likely be considered outside the bounds of respectability.

What should outlets that are trying to do a better job of achieving balance consider?

We probably don’t put enough emphasis on selection bias. The outlet’s choice of segment topic is more important than 1) the way the story is covered or 2) the things guests have to say about the topic. Topics have built-in skews. So, for example, it’s almost impossible for a panel discussion about Donald Trump’s refusal to release his tax returns to be considered a “pro-Trump” segment, regardless of how many pro-Trump panelists pad the bench. If you want to increase ideological diversity in media coverage, deciding who gets to pick the topic is more important than deciding who gets to talk about the topic.

You started off talking about geography and religion. Why is it a problem that journalists’ skews are more secular and cosmopolitan?

A journalist friend of mine who comes from a long line of Baptist preachers once told me about an evangelical rally in D.C. he attended where a pastor mentioned wanting to “slay all of congress.” He had to explain to his fellow reporters that being “slain in the Spirit” is something that charismatic Christians say (and that this pastor was not suggesting they kill members of Congress).

The point is that every group of people has certain shibboleths; the fact that so few journalists have a religious background makes them out of touch when it comes to covering traditional Americans who don’t live in places like New York City or Washington, D.C. To many journalists, religious people should be viewed with skepticism.

But can’t journalists learn about people who aren’t like them and cover them fairly? I mean, isn’t that part of the job?

Yes, but too often it comes across in a manner similar to an anthropologist observing some backward civilization. I think this bias is very subtle, but we still need to rethink some fundamental assumptions about the way we approach coverage.

For example, I recently heard journalist and author Krista Tippett talking on the Longform podcast about this, and she made an interesting point about people who are religious. If a reporter was writing a profile about an artist or musician, they might find some of the weird things he or she said to be mysterious, if mystical. Religious people are not given this same latitude for their numinousness; they are, instead, interviewed with the same degree of skepticism usually reserved for politicians.

You’re in the media. As a member of the media, aren’t you part of the problem?

I get accused of bias all the time. But it’s important to distinguish between opinion journalists and straight news reporters. Opinion journalists are paid to have a point of view, but we should still strive to be intellectually honest.

Okay—but you live just outside of Washington, D.C., and have worked in journalism for a long time now. Do you worry about being out of touch?

I think we all should worry about that. I am fortunate to have a lot of unique experiences to pull from.

My dad was a prison guard; I went to college in West Virginia. My mom voted for Trump. This is not to say I’m some blue-collar horse whisperer, but my background sets me apart from many of my Ivy League colleagues and competitors.

Like everyone, I was stunned by Donald Trump’s success. But my upbringing has helped make me more attuned and empathetic to the plight of so many of the working class white voters who, having cast their ballot for Obama twice, instead chose to pull the lever for Donald Trump.

Pauline Kael, an American film critic for The New Yorker, claimed to only know one person who voted for Richard Nixon. For journalists hoping to tell stories and enrich people’s understanding, being out of touch with a wide swath of Americans is a real indictment.

Since you mentioned Trump, how does he fit into all of this?

The irony, of course, is that this liberal media bias contributed to the election of Donald Trump. Conservative voters, tired of the bogus attacks and political correctness of the media, became inured to it. As Bill Maher admitted on HBO’s “Real Time” just before the election, liberals cried wolf so many times that nobody believed them when they warned about Donald Trump’s very real problems.

Laments about media bias are older than I am, and they will probably always be with us. In the past, however, discussions about this problem were somewhat academic. Today, this problem looks more like an existential threat. Americans increasingly distrust and dislike the media. They are tuning us out. We are not just competing with alternative new media outlets that have an ideological agenda; in some cases, we are competing against fake news sites.

To preserve a free and vibrant nation, political leaders must be held accountable. This is perhaps the fundamental responsibility of the media. While demanding transparency from our political leaders, it is incumbent upon us to hold ourselves accountable to the highest standards so that we might once again earn the right to serve in this vital watchdog capacity.