The news literacy program designed for middle schoolers at I.S. 303 Herbert S. Eisenberg in Brooklyn was launched years before the fake news phenomenon

In the run-up to last year’s presidential election, Kennady Wade found herself challenging her peers on the dubious stories they posted on social media, like links to obscure conservative blogs that claimed Hillary Clinton was a money-laundering devotee of the late radical activist Saul Alinsky who would flood the country with refugees if she won the White House.

But even though—or perhaps because—she was one of the top editors at The Kirkwood Call, the news website and magazine of Kirkwood High School in suburban St. Louis, she rarely if ever tried to debunk those myths. Politically conservative kids resisted her skepticism of the news they shared online because they considered the Call to be liberal.

“I know what they believe,” says Monique Foster, Wade’s then-classmate, now a freshman at Mississippi State University. “I see it all the time. Nothing is going to change my opinion. I don’t feel like I need to get into an argument. Your politics are right side or left side, and it’s not going to shift. If I knew someone had a different viewpoint on something, I would try not to bring it up. I would rather talk to my conservative friends about it.”

Exchanges like those between Wade and Foster dismay veteran journalism teacher Mark Newton of Mountain Vista High School near Denver. He has been trying to instill an appreciation for truth, accuracy, and the First Amendment among young people in classrooms for most of his life. With the advent of smartphones and social media, he’s seen a new information ecosystem flourish among students. Now, in the “post-truth era,” it seems as if that ecosystem embraces values that are the opposite of everything he’s been teaching.

“I felt like I failed as a teacher for 32 years,” says Newton, who is president of the Journalism Education Association, a group that includes many of the 8,000 journalism teachers at high schools across the country. “It’s clearly evident that what I’m teaching about the media—a vast number of people don’t get it.”

Newton is right. And studies of both education initiatives and cognitive biases suggest that, at a time when more critical media consumption is sorely needed, news literacy can be a difficult skill to impart.

A Stanford University study released late last year found that most middle school, high school, and college students were functional news illiterates. Eighty-two percent of middle school students couldn’t distinguish between a “sponsored content” advertisement and a real news story on the same website, the study found. More than 30 percent of high school students argued that a fake Facebook post masquerading as Fox News was more reliable than a real Fox News post. And over 80 percent of college students believed a website was a trusted, unbiased news source when a simple Google search would have revealed its ties to a Washington, D.C. lobbying firm.

The study showed that most young folks are completely unprepared to be responsible news consumers in the Internet age, says study co-author Sam Wineburg, a Stanford education professor. “What we need to think about educationally is a way that we cultivate, irrespective of which side of the political aisle we fall on in our educational system, a commitment to accuracy,” he says.

At a time when more critical media consumption is sorely needed, news literacy can be a difficult skill to impart

In the fight against misinformation and disinformation in the news ecosystem, journalism students like Wade and educators like Newton are struggling to understand not just the supply of “fake news” but the demand for it. It makes sense that impoverished Macedonian teenagers would spread lies online to make a buck. But why do people keep reading, watching, and sharing the stuff? Journalists, educators, foundation officers, and tech wizards are focusing on news literacy as a solution, despite questions about its effectiveness.

“No one is born with news literacy,” says Arizona State University journalism professor Eric Newton. “They learn it. The question is, how can they learn it well and enough of it so that it helps them get the news they need to run their governments and their lives?”

Stony Brook University’s Center for News Literacy is one of the leaders in the emerging field. In addition to including news literacy among the pool of required courses at the Long Island university, the center has partnerships with New York City’s public schools, the University of Hong Kong, and other institutions where news literacy is part of media, social studies, civics, and English classes. “I don’t think it’s sufficient anymore for journalism schools just to teach journalism,” says Howard Schneider, a former Newsday editor who is now dean at Stony Brook University’s School of Journalism. “Given these transformative changes under way, we need to take on a second mission that nobody has taken on. We need to teach the audience.”

The Trust Project at Santa Clara University, the American Press Institute, Poynter, and others have launched news literacy campaigns in recent years as the rise of fake news became a major story. Working with media outfits, fact-checkers, and journalism watchdogs, the new Facebook Journalism Project is now holding events around the world to determine how best to fund efforts to cultivate news literacy. Among the most high-profile groups working with Facebook is the News Literacy Project, a Bethesda, Maryland-based nonprofit that develops multimedia school curricula and other materials for thousands of educators around the country. Led by Alan Miller, a Pulitzer Prize-winning former reporter at the Los Angeles Times, the group is developing public service announcements on fake news and news literacy. “When I was a reporter, we had a saying: ‘Facts are stubborn things,’” says Miller. “Now it seems opinions are more stubborn things than facts.”

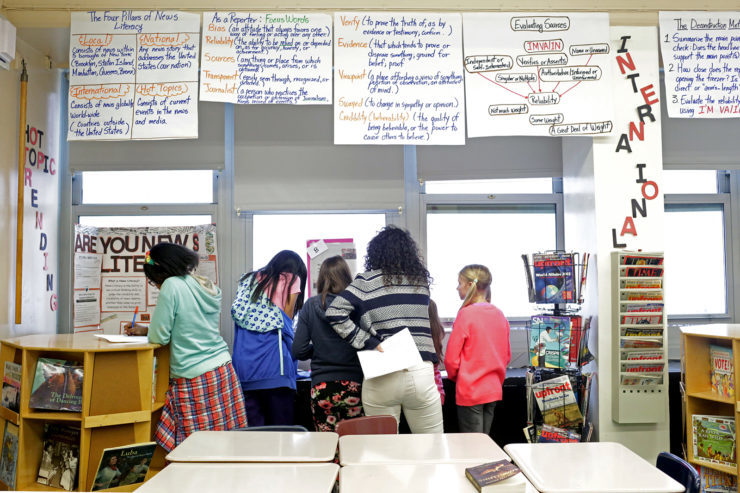

Students in a 6th grade News Literacy class examine an assignment given by their teacher, Marisol Solano (center,) at the Herbert S. Eisenberg I.S. 303 school in Brooklyn

Foreign news organizations have launched similar initiatives, according to a study by the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers. In France, the investigative news agency Premières Lignes produced an educational video showing the difference between a real conspiracy, like American tobacco companies lying about the dangers of smoking, versus a conspiracy theory, like whether the French government was involved in the Charlie Hebdo attacks in 2015. In South Africa, Media24 created an app that helps students and citizen journalists follow professional standards and post their stories to local news sites. The Indonesian daily DetEksi conducts a youth poll run by college and high school students that has been a major draw for young readers, inculcating the values of quality journalism.

The News Literacy Project and other American groups’ courses include lessons in identifying the difference between straight news, opinion, advertising, and propaganda to classifying primary, secondary, and other sources. They often include online testing where students must distinguish between news and other media. They also put students in the role of reporters, giving them firsthand experience in identifying and acquiring sources for a story. Lastly, they usually review the press’s role in a free society, a concept that news literacy teachers say is critical.

Too many students don’t appreciate the media because they don’t understand its special role as the Fourth Estate, a lack of understanding that has profound ramifications for democracy. “Finding a way to agree on what are the facts as a basis of discussion is essential for the country to reach any consensus on how you move forward,” says Miller. “We seem unable even to do that.”

One might argue that news literacy efforts face the same challenge.

In a field participants repeatedly describe as in its early stages, it is not clear if news literacy can actually be taught. Few argue that news literacy courses provide no benefit to students. Educators have demonstrated that, on a limited scale, they can make students a little savvier about the media. But whether those same educators can train large audiences to unmask fake news in the Internet age is an open question.

“When I was a reporter, we had a saying: ‘Facts are stubborn things.’ Now it seems opinions are more stubborn things than facts.” —Alan Miller, News Literacy Project

News literacy courses can make people appreciate the value of the press and accuracy and the importance of a well-informed electorate. Surveying around 600 Stony Brook undergraduates who took a news literacy course and about 400 who did not, a Center for News Literacy study conducted in 2010 found that the number of students who believe journalism protected democracy rose from 72 percent to 93 percent after a news literacy course. The number who believed the media played a watchdog role in society increased from 69 to 84 percent.

Those studies also suggest that the benefits of news literacy courses dissipate in the long term, however. A year after the course finished—the last time researchers polled students—those who believed journalism protected democracy decreased from 93 percent to 85 percent. Their faith in the watchdog role declined from 84 to 79 percent. A similar drop-off occurred in students’ critical thinking skills.

Stony Brook’s Center for News Literacy study found that slightly more students could better assess the reliability of information and the fairness of evidence after a news literacy course compared to those who did not take the course. A year later, however, more than a quarter were less likely to make that distinction. At the same time, students who did not take the course were more likely to correctly perceive whether a source was reliable and evidence fair a year after they were first tested—meaning they become in a sense more news literate over time than students who took the course.

Teachers corroborate these mixed results. They repeatedly say their students vacillate between news literacy and citing bad information. “The kids will get sucked into stuff,” says Liz Ramos, who includes News Literacy Project lessons in her 10th- and 12th-grade history classes at Alta Loma High School near San Bernardino, California. “It’s about constantly going over ideas with them. It’s something you need to constantly go through.”

One or two courses in news literacy won’t overcome the misinformation young people navigate every day, Wineburg argues: “The approaches that are being bandied about are doomed to fail. We are in a freaking revolution. We bank differently. We date differently. We shop differently. We choose a Chinese restaurant differently. We do our research differently. We figure out what plumber to come to our house differently. But school is stuck in the past. What we need to do is … think hard about what the school curriculum really needs to look like in an age when we come to know the world through a screen.”

Cognitive biases—the mental blocks, predispositions, and prejudices that lead consumers to choose between news sources—help explain why news literacy advocates face an uphill battle. Everyone has them, but some are more dangerous than others. “Thinking that snakes are dangerous is an adaptive bias that helps us stay alive,” says Matt Motyl, a psychologist at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “Thinking that anyone who disagrees with me is crazy or evil is not so adaptive, and is threatening to the health of democracy.”

Confirmation bias leads one to seek news that appeals to our preexisting beliefs (for example, liberals flocking to The Nation but eschewing The National Interest). Biased assimilation involves responding to news that challenges our beliefs more critically than news that confirms them (panning a critical report about genetically modified foods because one believes GMOs are key to ending world hunger.) Negativity bias leads people to pay more attention to bad news than good, a possible defense mechanism that might also lead one to believe illegitimate sources claiming that, say, vaccines are harmful.

Cognitive biases can cause news consumers to segregate themselves into online echo chambers where they embrace reporting that appeals to their sensibilities and reject whatever runs counter to them. The more one is personally invested in a point of view, the more emotional one is likely to become defending that perspective from alternative worldviews. That’s happened as mainstream viewers have segregated themselves among Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC. Now a new separation has opened between mainstream viewers and those who trust InfoWars and Breitbart News.

Teachers from elementary school through college, such as Kean University journalism professor Pat Winters Lauro, shown here, have been ramping up media literacy training in the classroom to help students identify and overcome the misinformation they encounter daily

It’s hard to change people’s cognitive biases, perhaps one reason news literacy efforts achieve such mixed results. Exercises that force people to consider alternative viewpoints before making a decision sometimes blunt confirmation bias, research shows. But those exercises can also backfire as folks conclude, after considering other views, that they, in fact, have been right all along. “It’s really hard to break people’s cognitive tendencies in a lasting way in real-world contexts,” says Motyl.

But people are still trying.

Both Stony Brook University and the News Literacy Project attack cognitive bias head-on, defining it for students, testing for it, and developing strategies to recognize and correct for it, including knowing how social media algorithms often filter information to cater to the user’s interests.

At Indiana University, computer scientists Filippo Menczer and his colleagues have developed a website called Hoaxy that aims to help readers fact-check stories on the Internet. It’s not a replacement for news literacy, but it could be a learning tool that provides background checks for online stories, including whether anyone has raised flags about their truthfulness.

Menczer’s childhood in Rome was partial inspiration for Hoaxy, which launched in December. He grew up watching heated debates in his living room. “My father was communist. My uncle was a fascist. Every Christmas, they had huge fights. They would yell at each other and storm out of the house,” he says. “I’m worried the way we are currently using social media may make it more difficult for those situations to arise.”

The executive director of the American Press Institute, Tom Rosenstiel, has taken a different tack. He believes transparency can help journalists improve readers’ news literacy. Providing lists of interviewees and copies of notes and documents alongside a story online gives readers proof the piece was based on sound reporting. Newsrooms might include that verification for enterprise stories or investigations, then expand the practice as they or software developers figure out the fastest and cheapest way to do it.

Too many students don’t appreciate the media because they don’t understand its special role as the Fourth Estate

A journalistic bibliography might feel too academic to journalists. But—noting that The New York Times recently used a footnote in a Jim Rutenberg article on “alternative facts”—Rosenstiel argues that reportorial endnotes over time would train readers in what to expect from quality journalism. “They are being conditioned to learn these are the things that make a story worthwhile,” he says.

Taking time to peruse interview transcripts or plug a headline into a fact-checking website requires the foresight and wherewithal that comes with mindfulness, a mental state that experts view as important for news literacy students. Mindfulness is a non-judgmental mental state, a kind of objectivity achieved by resisting the tug of one’s emotions on decision making. Mindful readers or viewers are less likely to react strongly to unpleasant stories or images or fall prey to distractions while consuming news. Whereas folks mostly operate in a world of “motivated perception,” seeking stimuli that reflects their desires, the mindful take a more open-minded, equanimous approach to new things.

Studying around 230 mostly well-educated people in North Carolina who took a weekly mindfulness course and practiced meditation exercises at home, Laura Kiken, a researcher in the Psychological Sciences Department of Kent State University, determined that one could remain mindful and resist cognitive biases for short bursts of time, like 10 minutes, with proper training that included meditation. Permanently altering a persistent cognitive bias could take two months of meditation exercises, she says.

Kiken is quick to note that she can’t prove that her work translates into news literacy, but she suspects it would. Mindful readers might be more open to valid, quality news that contradicted their biases. “I suspect mindfulness may help,” she says. “If you are short on time, motivational energy, you’re cognitively packed, you’re more likely to rely on your biases to guide your information processing and you’re maybe not going to be more careful. When mindful, you do not fight emotion. But you notice it and the very act of noticing it makes you less immersed in it.”

At the I.S. 303 Herbert S. Eisenberg middle school near Coney Island in New York City, teachers felt they had found a formula that works. Around five years ago, the school partnered with Stony Brook University to develop a news literacy program, including a classroom devoted to the subject and lessons from sixth to eighth grade that are part of the school’s Common Core curriculum.

Principal Carmen N. Amador and the school’s news literacy teacher, Marisol Solano, recalled how students recently analyzed the provenance of their sources in a classroom discussion about the ethics of zookeeping. They decided that an administrator from the National Zoo was trustworthy but biased, while students were split over the trustworthiness and bias of a former trainer at Sea World. Solano couldn’t produce studies proving her students had improved their news literacy, but the kids’ discussion made her positive that Eisenberg was sharpening the skills they needed to spot and shun fake news.

“The students, when they are not prompted, are asking each other questions and using that language: ‘Is that biased? Where did you hear that?’” says Solano. “That they are asking questions is one piece of evidence that they are becoming more news literate.”