The Kentucky Kernel’s legal battle with the University of Kentucky—over whether records in a sexual assault allegation involving a professor should be disclosed—is among a growing number of university crackdowns on student media. Marjorie Kirk, shown here, is editor of the campus newspaper

The Sun is far from sleepy, however. Like a growing number of university and college newspapers, it’s been producing bold and aggressive journalism.

Alone in the quiet newsroom, city editor Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs is recovering from an all-nighter he spent writing about a rare public hearing the previous day involving Cornell’s judicial administrator and an undergraduate charged with violating the campus code of conduct. The student was accused of leaking documents to the Sun disclosing that a working group on which he served might recommend Cornell consider transfer applicants’ ability to pay before admitting them, a departure from the university’s longtime practice.

The resulting stories and the newspaper’s coverage of the conduct case were mentioned in a Politico email newsletter and other national media, scoring more than 30,000 hits online on the day of the hearing—three times the entire newspaper’s typical daily traffic. “It’s interesting that the first public hearing in years directly involves the Sun itself, and we’re the ones reporting on it,” Bogel-Burroughs says with enthusiasm that belies his lack of sleep.

What’s increasingly inspired them, say student journalists, is the experience of witnessing a re-energized national media

Interesting, but not surprising. Student journalists nationwide are forcefully asserting themselves as they report on not just homecoming games and visiting speakers but about such high-profile topics as sexual harassment, athletic scandals, cost, privacy, and access for low-income applicants and racial minorities. They’ve exposed embarrassing hacks of campus IT systems, toxic mold in dorms, high-priced travel by trustees, previously undisclosed cases of sexual harassment by faculty and other university employees, and private comments by a college president who spoke disparagingly about academically struggling students.

This kind of coverage has invited conflict with universities concerned about their reputations in the eyes of legislators and prospective applicants, donors, and funders. Some institutions have taken steps to thwart their own student media, including locking them out of their offices, cutting off funding, and firing advisors.

Among the reasons student journalism has been getting more and more exposure: Publishing online vastly expands its reach beyond the campus cafeterias and dorms where students read their print editions. It has also filled a void left by cutbacks in coverage of the higher-education beat by many other news outlets. Some of the extreme responses by universities, too, have had the paradoxical effect of drawing more attention to the reporting that provoked it.

But what’s increasingly inspired them, say student journalists, is the experience of witnessing a re-energized national media. They say they’ve seen more of their classmates signing up to write for campus newspapers, and more considering careers in journalism. Bogel-Burroughs and his colleagues and counterparts, he says, are seeking to be “as aggressive as reporters as we see national reporters being.”

Universities and their campus media have been going head to head more publicly and uncompromisingly and with higher stakes than ever, according to organizations that monitor this and help defend them. The students also know they’re under a spotlight. “At a time when Donald Trump is shouting ‘fake news media’ on Twitter, we’ve really been inspired to keep pushing,” says Nicole Ares, managing editor and digital editor of the College Heights Herald at Western Kentucky University.

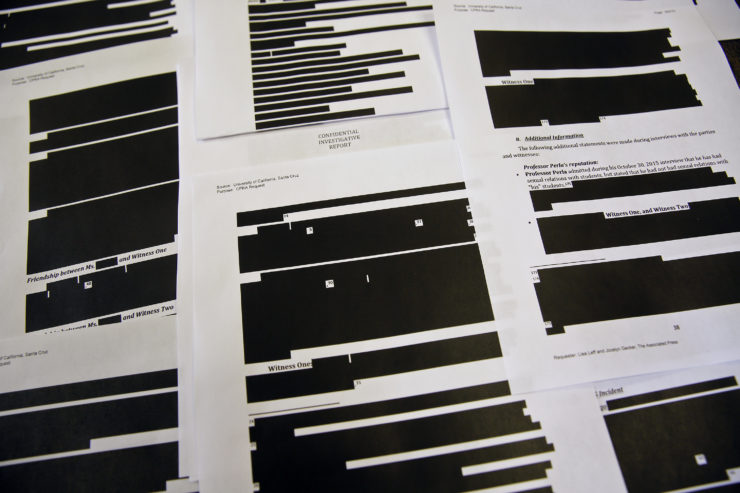

The Daily Californian used documents—such as this heavily redacted file of a sexual harassment case against a UC Santa Cruz Latin Studies professor—obtained through a public-records request to report on the shocking number of University of California employees who had violated the system’s sexual misconduct policies

When Western Kentucky refused its public-records requests for files of investigations into sexual misconduct by faculty and staff, the newspaper appealed, and the state’s attorney general ordered that the records be handed over. Instead, the university, in February, sued the Herald.

The other thing that has inspired her to persist with this story, Ares says, was a similar case at the University of Kentucky, or UK, in which the Kentucky Kernel student newspaper filed public-record requests for documents about a sexual harassment case involving a faculty member accused of groping students. The professor, who denied the charges, agreed to resign. The university wouldn’t release the documents, however, even after the state’s attorney general ruled that they were public. Instead, it also sued the newspaper.

Even though the information had already been leaked, UK said, it wanted to establish a precedent that victim confidentiality could be used as grounds to hold back records of investigations. If they saw that documents about sexual harassment cases might be made public, president Eli Capilouto said, victims would be discouraged from reporting it. He blamed the Kernel for a 37 percent decline in campus sexual misconduct reports after it began to cover the story.

Student confidentiality is often the basis for public universities denying records requests from student and professional journalists alike. A 1974 federal provision called the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA, says records maintained by an educational institution that identify a student cannot be released without the student’s permission. The Student Press Law Center and other advocacy groups contend that it is widely misused to deny requests for public documents, such as those in sexual harassment cases and athletics scandals. These groups want the opposite precedent set—that universities not be allowed to automatically keep information about sexual harassment cases secret by citing FERPA. Student journalists say that’s the only way to scrutinize how the institutions are handling these cases.

A circuit court judge in January sided with UK, though the newspaper is appealing and the state’s attorney general also is challenging the ruling.

New scrutiny of how universities and colleges handle sexual harassment and assault in particular follows national protests by students and pressure from the Obama administration, in response to which many institutions promised transparency and more attention to the issue. Student journalists on many campuses say they are holding them to that.

“We live in a world now where they can’t control that message any more. They can produce fun fluff pieces on how great it is to go to a university, but the student newspaper is writing about alleged sexual assault by the football team,” says Kelley Callaway, president of the College Media Association and director of student media at Rice University.

The Daily Californian at Berkeley, for example, using documents obtained through a public-records request, reported in February that University of California employees and contractors statewide had violated the system’s sexual-harassment policies at least 124 times in three years. These included top faculty, department chairs, and coaches, about one-third of whom were still in their jobs.

The University of North Carolina’s Daily Tar Heel has been trying since the fall to get the names of students found responsible for sexual assaults there, arguing that other students had a right to know. It sued, too, in November, after the university, citing the privacy of victims and witnesses, failed to respond to a public-records request. A judge ruled in May for UNC, saying FERPA superseded state public-records laws.

Universities and their campus media have been going head to head more publicly and uncompromisingly and with higher stakes than ever

The university has said its policies for dealing with sexual assault and sexual harassment “are among the best in the country, but we can’t see anything about how it’s being executed,” says Daily Tar Heel editor Jane Wester, who wrote a rare front-page editorial at the end of the spring semester to demand “that university officials speak clearly to us, their constituents, and stop acting like a business bound by profit.” UNC is still recovering from a scandal in which athletes were found to have taken courses that required little or no work and their grades altered to maintain their eligibility to play.

Vice chancellor of communications and public affairs Joel Curran responds that the scandal has resulted in the university becoming more, not less, transparent: “Are we always going to be aligned with the media? Probably not. But we’re as open as we can be in the [sexual assault] policy and how it works. We do make public what we can make public.”

Complaints that higher-education institutions are hypersensitive about their images are not unique to UNC. Universities are battling low public approval and mistrust. Nearly half of people surveyed by the nonprofit Public Agenda said that students now go into so much debt to get a higher education, it’s no longer necessarily a good investment. Nearly 60 percent said colleges mainly care about the bottom line, and 44 percent that they’re wasteful and inefficient.

Legislative allocations for public universities have only slowly rebounded after dropping sharply after the 2008 economic downturn; few states have returned to pre-recession spending on higher education. Private colleges are competing fiercely for a shrinking pool of applicants as a demographic dip in the number of high school graduates enters its sixth year, and enrollment declines.

Meanwhile, much more bad news originates in campus newspapers as off-campus ones cut back on higher-education coverage. Sixty-five percent of professional journalists on the education beat say they have little time for in-depth stories, and a third that their outlets’ education staffs have shrunk, according to a survey conducted last year by the Education Writers Association. More than 40 percent of higher-education beat reporters also have to cover primary and secondary schools. “College journalists almost have the field to themselves these days because they’re filling a vacuum,” says Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center. And colleges “are being more aggressively adversarial than ever” toward them.

The University of Central Florida, for instance, asked a court to order that its legal fees be paid by Knight News in a case the student-run website brought against it for failing to respond to a public-records request. LoMonte says he thinks it’s an attempt to discourage such lawsuits by ratcheting up the cost.

It was the third time Knight News has sued the university for blocking its access to documents. This time it asked for budget requests from extracurricular organizations submitted to the Student Government Association, which controls nearly $19 million collected from mandatory student fees. The university, citing FERPA, redacted the names of some student government representatives who made the funding decisions. “All the students here pay money, they give activity and service fees to the student government, and they have every right to know how that money’s being spent,” says Kyle Swenson, Knight News’s editor in chief.

A circuit court found for the newspaper and rejected the university’s argument that the names of student government members could be withheld as “education records” under FERPA. It also threw out the claim for legal fees. UCF has separately been reported to have spent at least $220,000 to block Knight News’s public-records requests. The university would not answer questions about the case, providing only a written statement saying it treats student journalists the same way it treats professional ones.

In one important way, however, the way that universities treat student journalists is different from the way it treats professional reporters: Universities have more tools available to slow down or discourage reporting by campus newspapers.

They can run down the clock, for instance. Campus editors say controversial announcements are often timed to coincide with academic breaks or final exams, or that their fights for information go on for longer than their time in college. Ares says her lawyers estimate the lawsuit seeking records from WKU could take as long as six years. “I won’t be around to see this play out,” she says.

Cornell Daily Sun managing editor Josh Girsky says the university asked him to delay reporting on that proposal to consider transfer applicants’ ability to pay until a final report was ready. He refused. “Maybe they thought they could avoid some of the uproar that might happen,” Girsky says. “But I think it’s very important to publish while deliberations are going on, and I think people should have a voice in the policies that affect them.” The university also asked that the Sun not run a story about a foreign hack of one of its schools’ IT systems, which, after cyber experts elsewhere said public knowledge of hacks helped improve security, it published anyway.

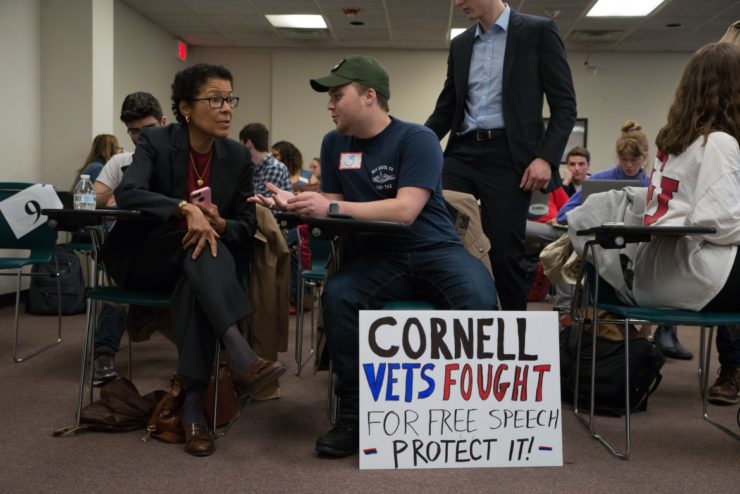

A student chats with a university administrator at the public hearing of a student who leaked documents to The Cornell Daily Sun, which received 30,000 hits online on the day of the hearing

Colleges unhappy with their student newspapers can also remove or fire faculty advisors. That’s what happened when The Mountain Echo at Mount St. Mary’s University reported that the president, in a private conversation, suggested that faculty encourage academically struggling students to drop out. “You think of the students as cuddly bunnies,” the newspaper quoted the president as saying. “You just have to drown the bunnies … put a Glock to their heads.”

When the story exploded nationally, the newspaper’s advisor was fired.

The advisor to The Pauw Wow, the student newspaper at St. Peter’s University in New Jersey, also was removed last year after a Valentine’s Day issue at the private Catholic institution included a story about pornography in intimate relationships, another about foods that serve as aphrodisiacs, and a third called “I Should Be Allowed to Like Sex.” The school’s president phoned the printer and ordered that the presses be stopped, according to the College Media Association, which censured the school.

The Mount Saint Mary’s advisor was rehired after a national outcry, and the Mount St. Mary’s president resigned; St. Peter’s has tentatively reached a settlement with the College Media Association to remove its censure. But many other student newspaper advisors are finding themselves under pressure with no such public fanfare, according to the American Association of University Professors, the College Media Association, the National Coalition Against Censorship, and the Student Press Law Center.

At least 20 advisors to student media have been pushed by university and college administrators to control, edit, or censor student journalism for coverage that was critical or put the institutions in a bad light, those groups reported in December. None of the incidents was publicized. “Universities realize the law is pretty much on the side of students when it comes to punishing student journalists, which doesn’t mean they won’t try,” says Robert Shibley, executive director of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. “But they can go after the advisors.”

In yet another case, Fairmont State University in West Virginia replaced the faculty advisor to The Columns student newspaper with an administrative “supervisor” after it reported an outbreak of potentially toxic black mold in a dorm. Student editors complained that the administrator threatened and intimidated them, and after yet another public outcry, he was removed from the position.

The advisor and staff alike at The Collegian of Hutchinson (Kansas) Community College were locked out of the journalism computer lab and the advisor suspended after the newspaper ran stories reporting about a conflict between a faculty member and an administrator. Two reporters were told in writing that they could face disciplinary action.

Other student journalists say they also have been pressured personally. In a lawsuit brought by the newspaper’s advisor, the editor of Northern Michigan University’s North Wind said she was warned by an administrator that continuing to run investigative stories about such things as trustees’ travel expenses threatened her career prospects.

University crackdowns on student journalists and leakers have the presumably unintended result of bringing more attention to their work, not less

At Cornell, the target was the whistleblower, Mitch McBride, who said he leaked documents from the working group about financial aid because he feared that reviewing applicants’ ability to pay would put at risk the “any person” part of the university’s mission to be a place where “any person can find instruction in any study.” “I think they wanted to explain it in their way. And I think that’s why they went after me,” says McBride, who took the unusual step of asking that his hearing on charges that he violated Cornell’s code of conduct be public.

Even though McBride was acquitted, he and student journalists said bringing charges against him could chill the willingness of other whistleblowers to come forward, a fact not lost on angry students and faculty who lined up outside a classroom where the hearing was being broadcast.

Cornell would not respond to this suggestion. John Carberry, senior director of media relations, who often deals with the Sun and its reporters, declined to discuss the case and said no one at the university would comment. He instead provided a link to a letter to the Sun from Provost Michael Kotlikoff that did not dispute the accuracy of the documents McBride leaked to the newspaper but complained they’d been reported “without context and misrepresented as an attempt to disadvantage poorer students and enroll more wealthy students,” which he called “a gross mischaracterization,” and that a “lack of respect for confidentiality undercuts our ability to work together.”

Of course, university crackdowns on student journalists and leakers have the presumably unintended result of bringing more attention to their work, not less. “If the university was trying to distract people from the substance of the documents” by putting McBride on trial, Bogel-Burroughs said, “the whole process had the opposite effect.”

In the end, the working group on which McBride served dropped the idea of considering transfer applicants’ ability to pay, as the senior vice provost in charge of the committee, Barbara Knuth, announced in the Cornell Chronicle, the newspaper produced by the university’s media relations department—bypassing the Sun. “It’s very much a shame that the Daily Sun picked it up,” Knuth would later say of the matter when she spoke before a Student Assembly meeting attended by people protesting the proposal and other changes to financial aid policies.

Crowdfunding campaigns have helped the Kentucky Kernel cover the costs of its legal defense, with many of the contributions coming from professional journalists, and The Daily Tar Heel’s suit against UNC was joined by The Charlotte Observer and The Durham Herald.

At Duke, when The Chronicle persisted in reporting that the executive vice president hit a campus parking attendant with his car and then yelled a racial epithet at her—he acknowledged unintentionally hitting the attendant but denied using the slur—it didn’t escape notice that the same executive vice president oversees the rental agreement for The Chronicle’s campus office space. But there were no overt repercussions, says Amrith Ramkumar, who covered the story and is now sports editor. “The administration knows they can yell at us off the record but they probably can’t do much more,” Ramkumar says. The Chronicle, too, he says, has a board of directors made up of alumni who are journalists, including at The Wall Street Journal.

It’s not just university bureaucracies with which student journalists often find themselves at odds, however. The student government at the University of Kansas cut the budget of The University Daily Kansan by 50 percent after the newspaper ran an editorial critical of a student government election. The decision was reversed after the Daily Kansan sued.

Like that editorial, much coverage by university media remains decidedly inward looking. But student journalists are also covering big stories off campus. The Indiana Daily Student at the University of Indiana ran a long, poignant feature about a Syrian refugee family after then-Governor Mike Pence banned Syrian refugees from the state. The student newspaper at California Polytechnic State University exposed sex trafficking in San Luis Obispo.

There are also signs that more students are newly interested in careers in journalism in what LoMonte calls the same sort of “Trump bump” law schools say may have contributed to an increase in the number of applicants this year.

Far more than usual turned up to apply for jobs at The Daily Tar Heel in the spring semester, for example, its editor, Wester, says. She’s since graduated and gone on to a job as a police reporter at The Charlotte Observer. Bogel-Burroughs has an internship with Reuters, Girsky with NBC News, and Ramkumar with The Wall Street Journal. Ares is heading off to graduate school in communication and Swenson, who hopes to become a financial reporter, has an internship at the Orlando Business Journal.