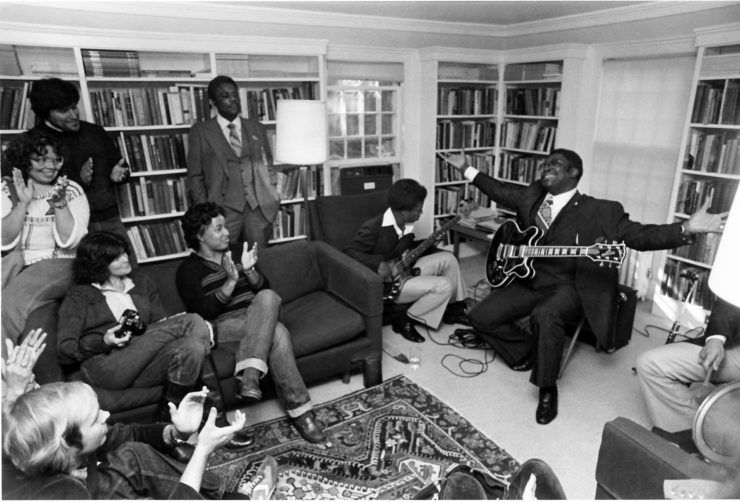

B.B. King performs for Niemans at Lippmann House in 1980

Journalism is in crisis; that is old news. But since I arrived at Harvard nearly three months ago, I have been struck at how much emotional and intellectual energy is being expended in the U.S. declaring that journalism is on the verge of death, if not already dead.

No one trusts us, I hear it said. No one cares about the truth. Fake news has poisoned everything, and the world is going to hell. Donald Trump’s unpredictability, un-presidential antics, and administrative chaos, of course, are major reasons for this sense of confusion and even despair.

It’s one thing to read about it in the news from my home in Kenya, thousands of miles away. It’s another to see the sad bewilderment upfront, particularly when I sense that the surprise is not merely that there is chaos and confusion but that there is chaos and confusion here, that this is happening to us.

One of the classes I am taking might give us journalists the tools we need to cope in these tough times: Cornel West’s “Race and Modernity,” which explores the ideas and legacy of three towering intellectual figures in the black tradition: W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, and Lorraine Hansberry.

These thinkers and writers are concerned with the idea of catastrophe—the devastation that has been visited on black people in America since its founding all those centuries ago and, by extension, the plight of oppressed people everywhere. With searing insight, Du Bois, Baldwin and Hansberry apprehend that catastrophe, in the sense of giving a solid form to what is otherwise dark and shadowy and ghoulish. They describe the various forms of death—existential, economic, social, political, physical and spiritual—that circumscribe the lives of black people in America. They excavate the grave, so to speak, and uncover all that America prefers to forget, ignore and deodorize.

But they do more than that. Even more importantly, they give us a hint of how to continue to exist in catastrophic times and in a world determined to see you dead, or at least quietly disappeared. How do you produce forms of beauty? How can you be tender, delicate — human?

West points us to an unlikely place—the Blues. Originating in the Deep South, the Blues is a genre of music that is particularly American and tied specifically to the experience of black people in America. Du Bois in his best-known work “The Souls of Black Folk” calls this music “the sorrow songs.” When Billie Holiday sings “Good Morning Heartache,” she is not denying or minimizing the fact that she’s hurting. She is not justifying or excusing the pain. She’s expressing a desire to live regardless, despite the daily wounds. When B.B. King sings “The Thrill Is Gone,” he’s not just lamenting the disappointment of a failed relationship. He’s speaking of freedom: “I’m free from your spell / And now that it’s all over / All I can do is wish you well.”

The Blues is not just a specific genre; it’s a worldview of resistance and a way of processing cruelty in the world. You find the Blues everywhere that people have had to grapple with unrelenting physical and spiritual violence—in jazz, in reggae, in hip-hop, in urban sounds from cities all over Africa.

It wasn’t incidental that Bob Marley called his band “The Wailers”. “A wail is not a whine,” says West. “A whine is the whimper of a victim. A wail is something different: It is existential angst deep from your soul transfigured into a shout.” You may be called nobody, and have nothing, but you can at least lift your voice.

These songs are not just the laments of simple relationship heartbreak (though relationship heartbreak is never simple). They are more than entertainment. They have a spiritual and moral character tied to something greater—the desire to carry on in a world that never expected you to last this long, where your very body was bought and sold, casually brutalized and callously beaten down. In such a world, even your walk can be a political act.

I come from a country that is yet to recover from the brutality and soul-shattering violence of colonialism, and its seamless continuation in the post-colonial state. Just this week, Kenya’s incumbent president, Uhuru Kenyatta has been declared winner of a repeat presidential election; the initial poll on August 8, 2017 was nullified by the Supreme Court, which cited massive irregularities.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch report that police killed at least 33 people, possibly as many as 50, and injured hundreds more, in response to protests following the elections. Leading opposition candidate Raila Odinga boycotted the repeat poll, arguing that no substantial reforms had been done at the electoral commission. Add to this the extreme dysfunction and intrigue at the commission itself—one senior election official was found tortured and strangled to death days before the first election in August, another senior electoral commissioner fled the country a few weeks ago, saying she feared for her life.

On paper, Kenya has been independent for over 50 years. But we are still grappling with catastrophe and, even today, the fact that we are still here is a testament to the small and large strains of resistance that have kept us going. This may seem depressing to a culture that has long learned to dominate nature and other people, and to a country that sincerely tells its children that they can be anything they want to be.

But there’s a reason there are no child prodigies in the Blues, West says, and I agree. You have to suffer, come face to face with loss, sorrow, grief and death—the things that make us grown adults. Without pain, we remain perpetual adolescents, pitifully clinging to misguided notions of innocence and exceptionalism.

Journalism needs to learn how to suffer and, yes, how to die. Only through death—coming to terms with your own wounds and scars—can one truly learn empathy, imagination and courage. Until then, there will only be the sad adolescent bewilderment that this is happening to us.