New York Times reporter David Rohde, center, interviews locals in the Kandahar region of Afghanistan, with translation help from local journalist Taimoor Shah (on Rohde's right). Rohde does not like using the term “fixer,” and has helped local reporters like Shah become bylined reporters with the paper.

Sanjay Jha was sitting in the back of a car with an American journalist who had hired him for a reporting project in Hyderabad, when the correspondent made passing reference to the term “fixer.” Jha took issue with the word. He paused to look at the reporter quizzically. “What exactly am I fixing?” he asked. “Your toilet? Am I a plumber?”

The reporter in the car was one of the co-authors of this article, and the conversation that followed with Jha—a respected journalist in his own right in India—helped lead to the largest study of the practice of “fixing” ever conducted. Our research study, “Fixing” The Journalist-Fixer Relationship: A Critical Look Towards Developing Best Practices In Global Reporting, surveyed correspondents and fixers about their relationship with one another, and what we found is a dramatic divide between how each member of this critical relationship views their own and each other’s roles, responsibilities, and contributions to the reporting on which people around the world rely.

“Fixers” are local people who work behind the scenes helping foreign correspondents get their work done. They do everything from serving as interpreters, to setting up hotels and drivers, to booking interviews and securing access to locations. They largely work in the shadows, often uncredited. This leaves the public in the dark about how foreign correspondence is done, and who may have influence on the international reporting itself.

While safety was foremost for correspondents, a larger concern for fixers was money

With funding from the Canadian Media Research Consortium and the University of British Columbia Faculty of Arts, we created an online survey of 20 questions which was distributed through email and social media to reporters and fixers worldwide beginning in mid-2016. More than 450 people from 71 countries completed the individual anonymous survey. At the end of the survey, the respondents had the option of volunteering to be interviewed. Over the course of 10 weeks in early 2017 we interviewed 35 respondents, most of whom had at least five years of experience working in some capacity in global journalism. Some respondents asked that we withhold their names to protect themselves, as well as their professional relationship. Graduate student Olivier Musafiri helped with the interviews and some of the data analysis.

What we found is that the dynamic of a deep-pocketed foreign reporter hiring a local journalist in an often-poorer country, to do his or her bidding, has inherent power dynamics that can lead to problems. Some highlights of our findings include:

- More than 70 percent of journalists say they never or rarely placed a fixer in immediate danger, while 56 percent of fixers said they were always or often put in danger.

- 60 percent of journalists state that they never or rarely give fixers credit, while 86 percent of fixers would like credit always (48 percent) or sometimes (38 percent).

- About 18 percent of the journalists report asking fixers about their political affiliation often or always, while only 6.6 percent of fixers disclose their political affiliation often or always.

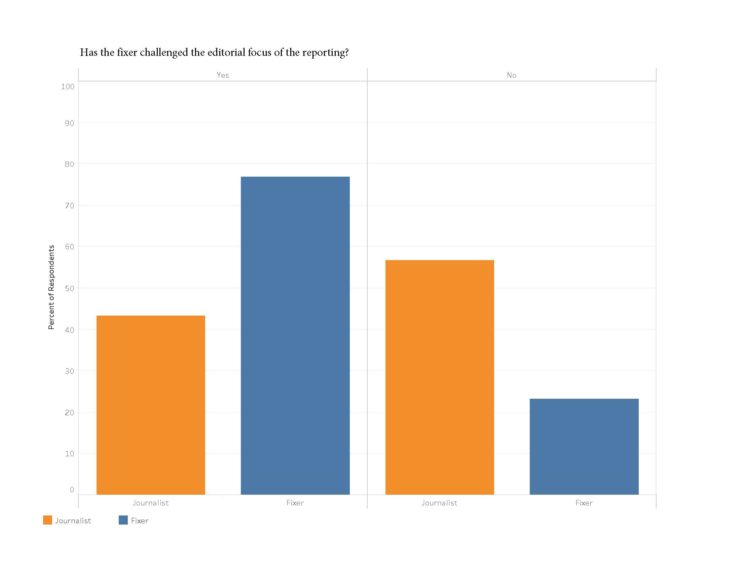

- 80 percent of fixers report questioning or challenging the editorial focus of a client’s story, while only 44 percent of journalists surveyed report being questioned or challenged by fixers.

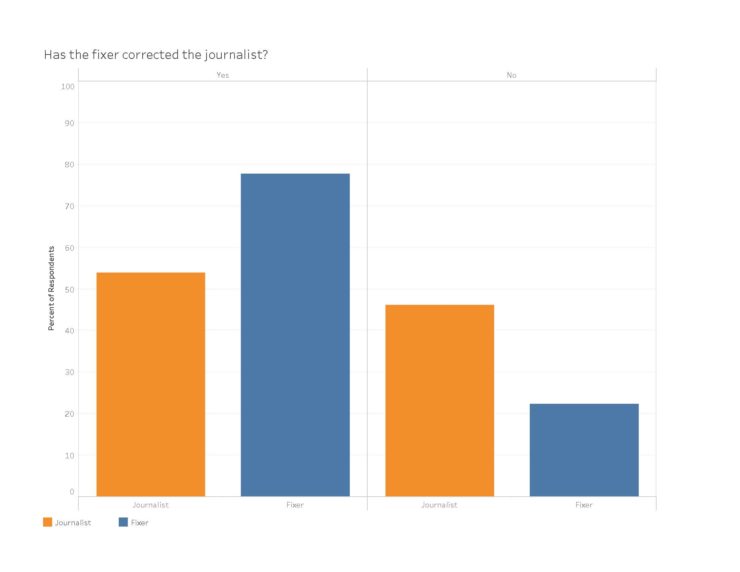

- Half the journalists say they have been corrected by a fixer, whereas fixers report correcting clients 80 percent of the time.

- 38 percent of journalists say they never rely on fixers for editorial guidance, while 45 percent of fixers say journalists always rely on them for editorial guidance.

- About a third of the fixers identify as “journalist-fixers” and 75 percent of fixers say they have another profession, with fixing only a minor or moderate source of income.

- The vast majority (92 percent) of journalists say they find fixers through “word of mouth,” rather than online fixer forums, lists of fixers, or social media.

What the data could not show, but subsequent interviews indicated, are underlying tensions that often remain hidden in professional interactions. A fixer with more than a quarter century of experience working with one of the American news networks, put it bluntly: “Unfortunately they still look at us as ‘brown’ people with funny accents, and though I have reported and done some of the most important and daring stories for [the network], it is a struggle to get a producer credit. Meanwhile, white kids—years my junior—get their names up [in the credits].”

Only about half of the journalists surveyed say they have been corrected by a fixer, whereas fixers report correcting clients nearly 80 percent of the time

The rare time fixers, frequently called “local journalists,” do come out of the shadows is when they are arrested, kidnapped, or killed. “Local journalists [working as fixers] no longer occupy the privileged position they once did,” said Courtney Radsch, advocacy director for Committee to Protect Journalists. “We have seen increased killings of journalists.” This, combined with a greater reliance on fixers in conflict zones, has created a scenario in which fixers are in ever greater danger, with a record number of journalists arrested last year, nearly all of them local reporters.

David Rohde, a veteran American reporter with experience in war zones, was kidnapped by the Taliban in 2008, along with Tahir Ludin, a local journalist working with him, and their driver, Asadullah Mangal. Rohde has been outspoken about the risks fixers face. “Local journalists are killed and imprisoned at a far higher rate than foreign correspondents,” he said. He noted that reporters and editors have started to pay more attention to safety concerns for fixers. “That is a positive step, but more needs to be done.” Many of the reporters in our survey were conscious of safety concerns, both during fieldwork and afterward. “If you’re going into dangerous parts of the world… it has to be fully understood at the outset for both of you that the fixer knows that risk,” said John Marks, a reporter with 30 years of print and broadcast experience in Europe and the U.S. And, he added, “you have to be careful that you do not put a fixer in a situation that could be dangerous to them after you leave.”

At the same time, it is the journalist who is often dependent on the local fixer to read the danger of a situation in a foreign environment. As Laurie Few, a seasoned investigative journalist and executive producer, explained, when it comes to the safety of your team, “you don’t have time not to listen [to the fixer],” and anybody who disregards a fixer’s advice “is going to step on a landmine, figurative or actual.”

While safety was foremost for correspondents, a larger concern for fixers was money. Our survey found the rate for fixers ranges from $50 to $400 per day. As Michael Armstrong, a correspondent with Global News, a major Canadian news network, put it, journalists “tend to show up with… more money… than [fixers are] used to making.”

Foreign reporters and their media organizations are clearly making more money off the reporting than the fixer, but compared to local wages in many parts of the world, the daily rate can be quite significant. “It’s all relative, right? It is on the cheap, fairly inexpensive for the news organization, but quite a lot of money for the fixers in a developing country,” said Melissa Chan, who has worked in broadcast journalism for more than 15 years, with both ABC News and Al Jazeera. “Depending on how you looked at it, right, which end of the telescope you looked at.”

This differential can lead to tensions, especially when fixers in poorer countries have to chase foreign news organizations for payment. Nejc Trušnovec, a fixer in Slovenia, said half the time he has to pursue clients for payment, often for months. “I had to write again, and again, and again to get paid because there were some hiccups going on. People would just forget to pay me, or they would send email to their accountant, and… [the journalists] would say, ‘Yeah, we are paying you next week,’ and then I had to wait for, like, almost half a year to get paid.”

Another perennial concern is byline credit. Most correspondents in our survey admitted they rarely, if ever, give fixers credit, and most fixers said they would like some sort of credit. A fixer in the Middle East who works on contract with an American news organization said, “I found lots of stories that were turned into pieces and my name was left [off the credits].” Rebecca Conway, a freelance photojournalist who works primarily in South Asia, said she tries to give byline credit when appropriate. “If a fixer is giving you editorial guidance, and you’re taking it, and it’s good, I think that’s above and beyond [what] a normal fixer is expected to do.” Priyanka Borpujari is based in India and worked with a Switzerland-based journalist last year on a story about outsourcing. “I told him that I cannot just work as a fixer,” she said. “Because I did the reporting from here [India], you know, from the factory, and he would be meeting the big officers in Switzerland, so the story is going on a joint byline.” The reporter agreed.

Most correspondents admitted they rarely, if ever, give fixers credit, and most fixers said they would like some sort of credit

This gets to the crux of what exactly defines the role of a fixer, and how much editorial agency they can or should have with a correspondent’s story. “[Reporters] come with a very preconceived idea of things and what they need,” said Ana Pereira Lehmann, a veteran fixer in Brazil who previously worked as journalist in the U.S. and the U.K. “I understand, they have to do a story, they have a topic, they have the idea, and it’s my role to try to get what they need… It’s very rare that they will change what they want or what they think they need, based on local conditions.”

With foreign reporters paying substantial day rates, fixers indicate having little agency to push back against the editorial forces from the home bureau. “They are hiring me, so they’re the boss,” confessed a fixer in Turkey. And Alexenia Dimitrova, an experienced Bulgarian journalist who fixes for documentary filmmakers visiting her country, said she only corrects her clients if they ask her. “If they [don’t] agree, they tell me and I’m completely okay with this. This is their film, their project, so I don’t feel very comfortable to argue with them. If this was my project I would follow my agenda, but because it is not mine, I completely agree with them.”

This was one of the most jarring distinctions between the realities for fixers and journalists—while 80 percent of fixers state they routinely correct journalists, only 44 percent of journalists say they have been corrected. Most correspondents indicated they appreciate the editorial insights—to a point. “You don’t want to go into a situation and pretend like, you know, because you read some articles and whatever, you know everything, because obviously …many of these things are incredibly complicated,” one reporter who works for Al Jazeera told us. “It’s a fine balance, I think, between taking [the fixer’s] insight and their opinions and evaluating them and listening to them, but also not relying on it entirely.”

A TV producer recounted a story in Rio about safety, in which a security consultant was interviewed about danger in Brazil. His fixer had misgivings about the source, but remained “completely professional” throughout the shoot, “but also made his views known to us when the time was appropriate… after the shoot was done when we were heading back to the hotel, but before the story aired.” The fixer explained that security consultants can exaggerate claims to drum up business, and the producer said he appreciated the feedback after the shoot, since speaking up during filming could have jeopardized the interview.

When asked if correspondents rely on fixers for editorial guidance, 38 percent said they rarely or never do, and many were quite vehement about wanting to relegate the fixer purely to a logistics role. A fixer in Jordan noted that, despite his experience and wall full of awards, his editorial judgment is still routinely questioned. “There is still deep mistrust of the quality of our work, unfortunately.” Mandy Clark, an experienced war reporter, put it bluntly: “I would never take editorial guidance from fixers. That would compromise the journalism.” She uses fixers to do straight translation, but “would never ask them how my interview went,” and if a fixer challenged her or provided editorial input, “I would listen to them, but I will not change my editorial judgment.” Glenda Gaitz, a longtime reporter with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, had a different perspective. “Normally, if they are fixers we use regularly, then their editorial guidance is considered, certainly because they are often living in the community that we are interviewing. But sometimes, you know, they might have a bias because of that.”

Several fixers indicated that they often quietly guide the editorial direction of a story to help foreign correspondents get the story right. Khalid Waseem, a fixer in Pakistan, said he presents options for interviews, but has a strong sense of who will be “chosen” by their client. “I’ve got a fair idea about it, but I will not push my decision down their throat… That’s purely their decision whom they should go for.” A production manager based in Chicago who works as a fixer for German correspondents said he similarly takes a more subtle tact when it comes to editorial direction. “My approach is typically to allow them a space… to draw their own conclusions… I serve more as the guardrails to keep them on the road to where they want to go. It’s up to them to decide which lane they want to drive in.”

The question of a fixer’s political affiliation was particularly contentious in this study. Only 6.6 percent of fixers said they “often or always” disclose their political or ethnic affiliations to their clients, and perhaps equally troubling, only 18 percent of the journalists surveyed indicated they “often or always” ask a fixer about those affiliation. “No, that’s not something we generally do,” said a senior producer at Al Jazeera English. “Often they are recommended by people we trust, so you kind of take it for granted that they’re legit. You know?” He acknowledged that this has led to concerns for his news organization. “We’ve had people be revealed as being very close to the government, or very close to the police. And then we never touch them again.” A veteran videojournalist with CBC said, “I’m sure somewhere, at some point somebody had mentioned… you should do thorough background checks on your fixers before you arrive. But I think it’s more of a case of learning… on the ground.”

Nearly 80 percent of fixers report questioning or challenging the editorial focus of a client’s story, while only 44 percent of journalists surveyed report being questioned or challenged by fixers

Only one of the fixers we interviewed acknowledged working for the government, and apart from addressing language, most did not reference their ethnic affiliations. However, interviews with reporters indicated that many correspondents are keenly aware of those affiliations.

The Al Jazeera English senior producer recounted the story of corresponding with a fixer for a project in Mali. The fixer’s email address referenced “Azawad,” a term related to the Tuareg homeland independent movement. “He’s probably not going to be able to get those government interviews,” the producer acknowledged, and he ended up using a different fixer for the project. However, if the initial discussion had been over the telephone rather than by email, the producer admits he might have hired the man, and his team could have had challenges in the field and may have even been put in jeopardy.

Reporters indicated using their fixer’s political or ethnic affiliations to open doors as well, but those connections can also be liabilities. A journalist with experience in Pakistan spoke of working with a fixer from a “ruling, elite, liberal, Islamabad crowd” who could not access tribal communities, so he turned to his driver who was from a tribal region to access local people for a story. A reporter working for The New York Times on assignment in Brazil had a similar story about using a driver with connections to the native rights movement to help earn the trust of indigenous interview subjects, but at the same time, that driver caused tension with farmers combating tribal land claims. Lameck Baraza, a Kenyan reporter who also works as a fixer, spoke of his own challenges reporting in a country with deep tribal and religious divides, admitting: “There are areas where I cannot be able to access because of the tribe I belong to.”

Many fixers we surveyed acknowledged they have political affiliations and perspectives, but said they try not to let these seep into their work with correspondents. A fixer in Venezuela, where political tensions are particularly high, said, “I have done jobs that would make the government look good, even though I don’t like them. Because you are supposed to be like that… You have to be fair with the story.” Anca Paduraru, a veteran Romanian reporter, recounted an instance in which she used a Hungarian-speaking fixer in an ethnically-Hungarian part of the country, and noticed that “he was translating everything through this thick glass, still feeling under siege,” skewing what people were saying through his own political lens. “People who are locally embedded there, they have more expertise… but at the same time, because they are part of the fabric, sometimes they lack the perspective.”

Some media organizations have started trying to offer both transparency to the public and credit to the local reporters, by adding fixers’ names to “additional reporting” tags at the ends of stories, and in some cases even offer co-bylines.

David Rohde says he used “local journalists and translators” in his reporting in Bosnia for The Christian Science Monitor and in Afghanistan for The New York Times, noting he prefers not to use the term “fixer.” In recent years he has co-bylined stories with local reporters in war zones, and said news organizations have started crediting them for several reasons. “There has been a push to be more transparent about who, exactly, is reporting a story, which has resulted in more bylines and contributed reporting credits,” he said. “I support and embrace that change. As reporting has grown more dangerous, the contributions and sacrifices of these journalists should be recognized.”

Given the findings of our study and the inherent power differential in the fixer-foreign correspondent relationship as it has long been practiced, we believe that a critical next step is to examine different approaches to foreign reporting.

Nonprofit journalism organizations have experimented with a variety of approaches to global reporting, challenging the fixer-correspondent model altogether

A number of alternative models of global reporting have emerged, which are challenging the well-worn practice of “foreign correspondence.” Some of the most effective recent global reporting stemmed from a fixer-free project by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which brings together reporters around the world to share data and co-report stories. Bastian Obermayer, a reporter with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, received a leak of more than 11.5 million secret documents—known as the Panama papers—related to offshore accounts. With the help of the consortium, he and his colleagues brought together journalists from more than 80 countries to co-investigate the use of these funds to hide and launder money. Obermayer said he likes working auf Augenhöhe, referring to a German expression of being at the same eye level. “No one is senior or higher than the other,” he said. “It’s colleagues of different countries working on the same stories from different angles. We see different parts of the same picture, and that is very helpful.” He said each reporter “plays the stringer” for each other, providing local knowledge and context, but maintaining co-authorship in the reporting. Robert Cribb, one of the reporter participants from the Toronto Star, has worked with fixers in the past, and said, “It [the Panama Papers model] is far better than a fixer arrangement… This is a partnership of equals, each in pursuit of the same story, each with expertise and access to separate pieces of a puzzle, mutually driven to produce the most comprehensive portrait possible. The resulting series of stories in papers around the world won the 2017 Pulitzer for Explanatory Reporting, and the recent Paradise Papers leak has generated a new series of revelations about offshore tax havens.

Nonprofit journalism organizations have experimented with a variety of approaches to global reporting, challenging the fixer-correspondent model altogether. The U.S. nonprofit Round Earth Media pairs an American reporter with a local journalist, but gives them equal editorial credit, with no one relegated to the “fixer” role. The Global Reporting Centre, with which both authors are affiliated, has given wearable cameras to reporters in Somalia to document their reporting from their vantage point and has fostered “empowerment journalism,” in which editors work with local storytellers to help them tell their own stories from their own perspectives, without the editorial imprint of a foreign correspondent.

Syria Direct is a nonprofit based out of Jordan, which has trained more than 100 Syrians to do reporting in their own country and share stories with the world that foreign reporters simply cannot access. It was founded by longtime CBS News fixer and producer Amjad Tadros, who saw the editorial need to give Syrians a way to tell their stories and also felt it was the right time to elevate locals beyond the subservient fixer role. “From the beginning of the Syrian revolution, I realized that there was a huge need for independent and unbiased reporting out of Syria,” said Tadros. “So we built a training center to teach young aspiring Syrian journalists the ABCs of journalism and how to report the truth.”

What these new organizations, and the data from our survey shows, is that the media landscape is evolving, and the role of the “fixer” is quickly changing along with it. The response to our study, particularly from veteran foreign correspondents, has been overwhelming, with a number of them noting that the fixer-correspondent dynamic always bothered them, but it seemed to be the only way to do global reporting. Clearly—if we listen to the fixers as well as the journalists—it isn’t.