The Kansas City Star’s transparency team is developing a model corrections policy, one of many efforts news organizations are making to gain trust and fight misinformation. From left, Eric Nelson, audience editor; Mará Williams, education reporter; Mary Kate Metivier, growth editor; Kathy Lu, enterprise editor; Ian Cummings, police reporter; Chick Howland, projects editor

Frontline executive producer Raney Aronson-Rath was in her office late last summer when special projects editor Philip Bennett walked in. He’d just been watching the raw footage from Frontline’s upcoming documentary, “Putin’s Revenge,” a two-part program about Russia’s attempts to influence the 2016 election. The interviews were amazing, he said. What if they put them online?

All of them.

“We’d been talking for a long time about what we could do at Frontline to really put a stake in the ground, that we are committed to transparency,” Aronson-Rath says. “A lightbulb went on, that this is the one we should go big on.”

The production team swung into action. At the same time editors and interns were working to produce the program to air that fall, behind the scenes they were also preparing 70 hours’ worth of interviews to post on the web. They fact-checked each, and vetted them with lawyers with the same care they did for the documentary itself.

Frontline’s Transparency Project is one of a number of new attempts by media to open up the process they use to create their journalism to engender more trust with audiences

But Aronson-Rath and her team didn’t want to just dump 56 interviews for audiences to sift through on their own. They used open-source software Bennett had helped create to make the films searchable by text, so viewers could easily find footage on specific subjects. They could even splice out a section and share it on social media. The result is both an exhaustive look at the issue of Russian hacking and an unparalleled look behind-the-scenes at the reporting process. In four months, the videos had more than 300,000 views, with 40 percent of web traffic referred by social media. What’s more, visitors spent twice as long with the interviews—an average of 28 minutes, much longer even than Aronson-Rath and Bennett anticipated—as the average visitor to the Frontline site. “Things that I myself wouldn’t have considered as part of the story now have relevance. It gives me a moment for pause. I am now watching from an expanded viewpoint and it’s interesting to see what is corroborated through other sources and what is not,” one viewer commented.

The Transparency Project, as Frontline is calling the effort, is one of a number of new attempts by media to open up the process they use to create their journalism to engender more trust with audiences. In a January Gallup/Knight Foundation poll of more than 19,000 Americans, respondents ranked their trust of media at only 37 out of 100. Just 50 percent of respondents said they had enough information to sort out facts in the face of media bias, down from 66 percent in 1984. Among Republicans, that number was even lower, only 31 percent.

Frontline has long been putting the complete transcripts of its interviews online—but putting the searchable videos online is a dramatic expansion of that proposition, laying bare the process of making documentaries, warts and all. “You see the real deal, people swiping their face, laughing, looking nervous,” Aronson-Rath says.

In many ways, the new push for transparency is a response to the current media environment of “fake news”—both the dissemination of actual false stories online and through social media, and the cries from the current administration that stories it doesn’t like are “fake.” As more and more Americans get their news through social media, content gets divorced from context that allows readers to decide whether a story is trustworthy.

“People are getting their news through every possible medium and on every possible device,” says Melody Kramer, senior audience development manager at the Wikimedia Foundation and columnist for the Poynter Institute. “It’s a challenge to figure out the veracity of the information, where it came from, what the point of view is, or how it was put together.” That creates more of an imperative for news organizations to pull back the curtain to explain to readers how they report and write stories. “It becomes incumbent upon organizations—that are trying to improve our lower-d democracy—to open up a window into how they do the work they do.”

At the same time, transparency can serve a defensive function, insulating the media from attacks of political bias or unfairness. As far back as 2009, Harvard technologist David Weinberger declared that “transparency is the new objectivity,” making a writer more credible in the eyes of readers not through adherence to a supposed standard of impartiality, but by making clear the “sources and values that brought her to that position.”

Among those organizations leading the current charge to increase transparency is the American Press Institute (API), which in 2014 produced a report entitled “Build Credibility Through Transparency.” The report advocated for publications to “show their work” by being clearer about their sources and correcting mistakes. In the run-up to the 2016 election, API consulted with news organizations about how to better disclose sources, using PolitiFact as a model. But it was unprepared for the level of hostility toward media and the allegations of bias and “fake news.”

“That’s when we started seeing a problem with misinformation, of which ‘fake news’ is part of that universe,” says Jane Elizabeth, accountability program director, who was surprised by the lack of media literacy among audiences and their willingness to believe outlandish stories with little sourcing, such as the debunked Pizzagate conspiracy theory. “Readers were confused and unable to tell the difference between misinformation, disinformation, and ‘fake news,’” Elizabeth says.

She places most of the blame on the current administration for deliberately sowing that confusion. “Trump’s candidacy had everything to do with this,” she says. “It was the type of campaign we had never dealt with before.” At the same time, she faults the media for not opening its doors to show the level of editorial care and vetting that goes into the news. “People think anyone can write something and press a button and it appears online.”

In an effort to increase transparency, Frontline posted dozens of interviews—with over 70 hours' worth of video—garnered from the raw footage for their fall 2017 documentary "Putin's Revenge"

The first step toward transparency, she says, is to listen to readers about what they don’t know—and what they want to know—about how news is gathered, verified, and reported. “Otherwise, you are just divulging the wrong things.” Some things that might seem obvious to journalists, such as the ethics of using an anonymous source, may be opaque to readers and sow confusion and distrust.

API is not the only organization working with publications to improve transparency. Transparency advocate Josh Stearns of the Democracy Fund has spent the last two years working with newsrooms across New Jersey on how to better engage with readers and open up their reporting to scrutiny. While such initiatives can be time- and resource-intensive, he says, they can also help bolster revenue by explaining the value of rigorous reporting.

“Helping people understand the labor that goes into reporting, is a powerful way to build a relationship with the reader that will cause them to want to support it,” Stearns says. Such support can go beyond merely financial. “If we want the public to stand up for our rights for FOIA [Freedom of Information Act] requests, or when local mayors want to block us, then we want to have the public’s back and we want them to have ours.”

Other active transparency initiatives include the Trusting News project run by Joy Mayer and supported by the Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri, which has surveyed thousands of journalists and readers and is working with 14 newsrooms on experiments to engage more authentically with readers; and the newly launched News Co/Lab, funded mainly by the Facebook Journalism Project and run by veteran journalist Dan Gillmor at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University, which is partnering with the McClatchy newspaper group.

One of the most ambitious efforts to improve media transparency is the Trust Project, an initiative of the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Led by journalist Sally Lehrman, the project worked with newsroom leaders from 75 publications to develop a common set of standards for transparency it calls “trust indicators.” In November, about 10 publications began rolling out the indicators worldwide, including The Economist, Mic, and The Washington Post. Significantly, the project has gotten social media sites and search engines including Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Bing on board as partners; the sites have agreed to start using the indicators in their feeds to give users a measure of the trustworthiness of articles.

In many ways, the new push for transparency is a response to the current media environment of “fake news”

“In the case where the work is divorced from the brand, you can see some of the markers that might help you know this piece of journalism and the quality behind it,” says Lehrman. Unlike, say, a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval, which would rely on an outside entity to certify a brand as trustworthy, the project presents a set of guidelines to publications they can adapt as they see fit, under eight headings, including standards and practices; author expertise; citations and references; and diverse voices. (Partners are free to use the TrustMark, a T logo designed by the project, or not.)

Under standards and practices, for example, the project requires that organizations clearly post their mission statement and ethics and corrections policy, both on a site level and with each individual piece. “These are often straightforward to journalists, but at the same time they are not often spelled out,” says Lehrman. “A lot of people don’t realize they exist.” Even in cases where sites include such policies, they are often hidden, buried on a second or third page on their website.

In addition to providing greater information about the publication, Lehrman and other transparency advocates are also pushing to include more about story authors, including their local or demographic background, years of experience in covering subject matter, awards they have won, and languages spoken—which is especially important for those covering minority or refugee communities.

Publications may also consider including a statement with stories they publish, particularly for stories that might be controversial or political in nature and open themselves to criticism. “It really forces the reporter to think about, why did I do this story, why was it important?” says Elizabeth. For example, a story written in a newspaper in a farming state about the use of toxic fertilizers could open journalists up to allegations of bias against the farming industry. “You really need to explain why you are stepping into this volatile subject,” says Elizabeth. “We are doing this story because our state has the highest percentage of dangerous nutrients in the water. Just so people don’t think, ‘look, that liberal democrat is trying to ruin our economy,’ just to show it’s a serious topic worth consideration.”

Just as important is that publications come clean when they make errors. Publishing on the web, it can be tempting to make changes on the sly, hoping that readers won’t notice. But that’s bad practice, say transparency advocates. Not only do readers notice when a story changes—which may increase skepticism over time—but also consistently seeing corrections on other stories might increase their perception that stories without corrections are accurate.

As News Co/Lab’s Dan Gillmor says, over time that may cause the public to believe a publication less, but trust it more. “The more you explain what you screwed up on, the more people are going to realize that journalism has its flaws, so the belief that any given story is 100 percent correct will drop,” says Gillmor, who is working with The Kansas City Star to develop a model corrections policy. “But I would hope that the trust in journalists to work really hard to make sure you know about the mistakes and correct them would improve.”

Transparency advocates recommend making corrections at the same level as the original mistake—if the error was on the front page, then the correction should be, too. For stories online, corrections should be clearly noted at the beginning or end of the article. Some publications are experimenting with putting corrections inline, either through crossing out and inserting text or noting corrections in the margin with a link to the corrections note.

Furthermore, a growing consensus among advocates is that the old adage that you don’t repeat a mistake in making the correction is no longer true. Because users may not be reading the publication daily or have seen the original story, it raises more questions than it answers to leave readers in the dark about the original error. Rather, the correction should clearly state the original error, as well as the correct information.

The first step toward transparency is to listen to readers about what they don’t know—and what they want to know—about how news is gathered, verified, and reported

The big question right now is whether such transparency will lead to an increase in trust. Research by Michael Koliska, a Georgetown University communications professor, suggests that there are no easy solutions when it comes to creating more trust. For his Ph.D. dissertation, published in 2015, Koliska set up several experiments in which he gave six versions of an article with varying degrees of information, from one that didn’t even have a byline to one with a byline, author bio, and information about the sources and production process.

The additional information, however, had no effect on whether readers found the story more trustworthy. In fact, says Koliska, readers barely seemed to register it. When he included a picture of the journalist on the page, and then showed a lineup of pictures afterwards, participants only picked out the right one about a third of the time. “There are a lot of these kinds of things that people just didn’t care about,” he says. “The transparency information was too peripheral to the story.”

In another paper published in 2016 in the Journal of Media Ethics, Koliska and his colleague Kalyani Chadha argue that rather than “digitally outsourcing” transparency information by adding transparency features to web pages or publishing separate stories about the process behind the article, journalists should work the information into the story, giving more background on the process and extent of the reporting and sources consulted as part of the story itself rather than relying on hyperlinks or author bios.

That doesn’t mean that providing transparency indicators isn’t worthwhile, says Koliska. As awareness of “fake news” and disinformation grows, it may cause people to seek out more information about transparency. “They will realize that they are not getting the high-quality product they want—they are getting McDonald’s sold as a Whole Foods meal, and crave something better,” he says.

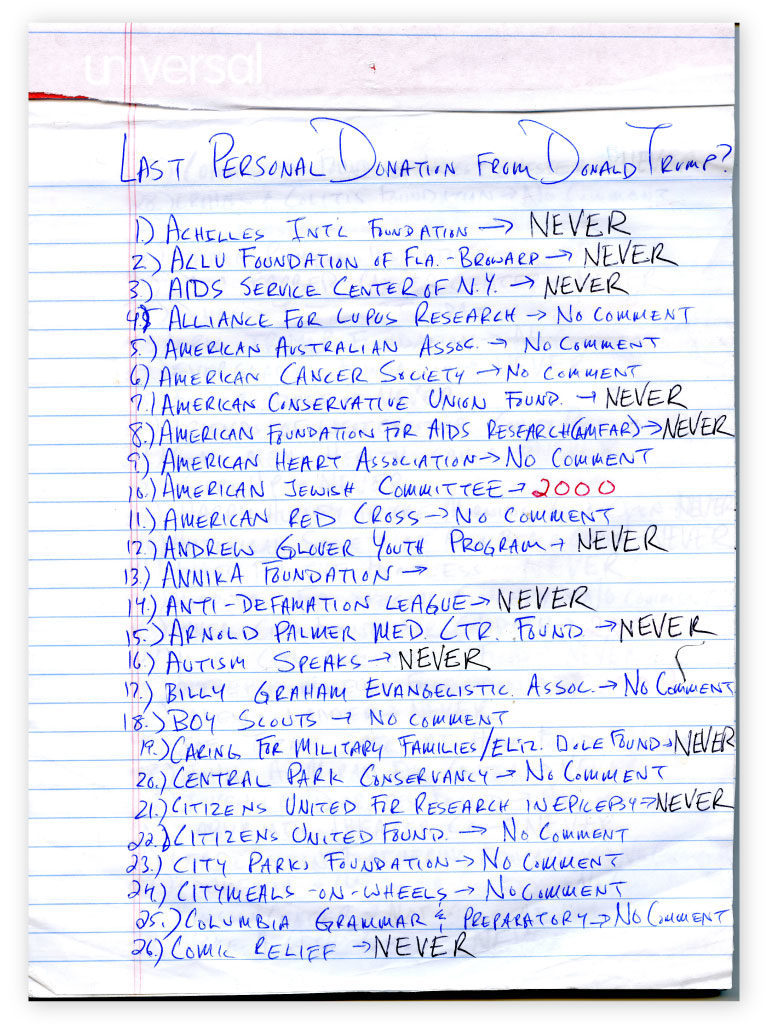

A page from David Fahrenthold's notebook documenting Trump's charitable giving—or lack of it. The Washington Post posted his progress on Twitter, sharing his notebook pages and getting tips from followers in return

Research by the Trust Project shows that may already be happening. Working with the Center for Media Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin, the Trust Project funded a study in which some 1,200 participants read online articles on different topics; some included the trust indicators, such as author bios, links, a “Behind the Story” companion article, and an indicator of whether the publication belonged to the Trust Project.

A small majority felt that such indicators would increase their trust of the publication, with the most (63 percent) citing the Trust Project logo, followed by a “Behind the Story” section (59 percent) and a list of corrections and ethics policies (53 percent). In addition, by a small but statistically significant margin, readers were more likely to use adjectives like “reputable,” “reliable,” and “can be trusted” for articles with indicators. “As newsrooms grapple with ways to win over doubting audiences, we find the study results encouraging,” the authors of the study noted. “The results … demonstrate that Trust Indicators can affect what people think about the news.”

As much as the online environment has eroded trust and created the need for more transparency, it also offers unique tools to increase transparency. As Frontline’s Putin documentary shows, nowhere is that the case more than in allowing journalists to “show their work” by providing access to the original source material so readers can make up their own minds about how it was used.

The Trust Project has advocated for a separate “citations and references” box that lists the key sources an article relies on; some partners such as Mic and The Economist are already using those boxes. When the project did a focus group to gauge their effectiveness, they found they increased perceptions of credibility even if readers didn’t click through to the underlying sources. Just letting the reader know that a journalist conducted additional research, even if it wasn’t included in the piece can increase reader confidence. “What if at the end of the story you listed the number of sources you reached out to, even though 20 of them were on background,” Stearns proposes.

Some publications are taking sourcing to the next level by including not only interviews, but underlying documents and source material to bolster claims in a story. ProPublica has long been a leader in this endeavor, using Document Cloud to upload and annotate documents for readers to peruse. “It has always been core to how we do our journalism,” says editor in chief Steve Engelberg. “In an era of complaints about fake news the best answer we can have in the fact-based universe is to provide the reader with as much fact as possible.”

For a story about death and complication rates by surgeons in 2015, ProPublica included a Surgeon Scorecard with a searchable database readers could use to look up specific doctors. The site also included a detailed discussion of its methodology for calculating rates, quotes from experts backing up their methods, and an editor’s note from Engelberg describing the reasoning behind the story. At the end of the note, Engelberg invited criticism from readers with a dedicated email address to receive them. While the site has pushed back against some of the criticism, it has taken some of it to heart, such as the fact that it only takes into account inpatient procedures, and will be using it to adjust their methodology for a planned Surgeon Scorecard 2.0.

ProPublica has made a habit of responding publicly to its critics, even when they publish their critiques elsewhere—acknowledging it when they feel the critics have a point, and pushing back when they feel like they don’t. “At the end of the day, we live in a universe where people are going to say things about your work, and there is no waving it off, like we have the printing press and you don’t,” Engelberg says.

In some cases, ProPublica has seen unintended consequences from its transparency—as was the case when it published a database of rates of prescriptions by doctors to draw attention to an epidemic of overprescribing opioids and other potentially dangerous narcotics. Analyzing web traffic, ProPublica’s editors noticed an uptick in traffic to the database, after Google searches such as “doctors who prescribe narcotics easily,” implying that readers were using the database to find doctors to prescribe them drugs.

Rather than pulling the database, ProPublica made the fact a further exercise in transparency, running an editor’s note explaining the problem, and adding a new disclaimer to the database warning about the dangers of addictive drugs. “This is an ethically tricky area,” says Engelberg. “We weighed the possibility that we were going to make it worse, but if you are in a glass house cajoling institutions to be transparent, then to know something about our work and not make it public seemed against the principles of what we do.”In deciding whether and how to release controversial documents, the more publications can let the reader into their decision-making process, the better they might be received by audiences. In January 2017, for example, when BuzzFeed released the Steele dossier containing allegations that the Trump administration colluded with the Russians, for example, it provided little explanation of the pros and cons of making the unverified document public—saying only that it wanted to let “Americans make up their own minds about the allegations.”

The big question right now is whether such transparency will lead to an increase in trust

Arguably, the publication could have taken readers behind the scenes to provide more detail about how they made this tricky journalistic decision, and how it aligned with their ethical and procedural policies, says Elizabeth. Such a thoughtful explanation may have mitigated some of the questioning and backlash it received from politicians and other news outlets about the choice. “I do believe BuzzFeed editors could have offered readers a little more gut-level transparency about their decision to release the dossier,” Elizabeth says. “But every one of these situations is an opportunity for all of us to figure out how to do it better next time.”

In addition to opening up their sources to scrutiny, some publications and journalists have taken the public inside the reporting process itself—as The Washington Post’s David Fahrenthold has done while reporting on Donald Trump’s supposed donations to charity. From the start of his reporting, Fahrenthold posted his progress on Twitter, showing his followers photos of his notebook with charities he was exploring, and even trading barbs with Trump himself. The openness paid off with members of the public, and even other journalists tweeting him tips—including one Univision journalist alerting him to the location of a portrait of himself Trump had bought with charity money, hanging on the wall at a Florida golf club.

When the nonprofit Project Veritas set up a sting operation to trick the Post’s reporters with a false claim of having been impregnated by U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore, the Post produced a story and 10-minute video about how it uncovered the sting, and even set up a sting of its own, showing the woman in an interview with a Post reporter, and explaining why it broke the agreement of confidentiality, since she had misrepresented herself in an attempt to embarrass the paper.

Washington Post reporter Stephanie McCrummen interviewing Jaime Phillips, who approached reporters with a false claim about being impregnated by U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore. The newspaper set up a sting of their own, and explained how they uncovered Project Veritas’s attempts to embarrass the paper

The Post further elaborated on how it broke the story about Roy Moore’s legitimate accusers in a video produced by reporter Libby Casey, part of a new series called “How to Be a Journalist,” which seeks to take readers inside the goings-on of the newsroom. “I was getting so many questions from friends and other people who aren’t in media about how we do what we do,” she says. “It showed me that with a little transparency we could turn our storytelling around to show how we do our work.”

Casey interviews her colleagues in an irreverent, almost jaunty style in an effort to present them in an authentic, human light. In interviewing reporter Stephanie McCrummen about the Roy Moore story, for example, she discusses the anxiety reporters feel knocking on doors with a notepad ready. Another video features database editor Steven Rich, who describes how he submitted 1,500 FOIA requests last year—detailing how readers can submit their own open records request to the government. “If we can demystify the process, it does empower people to learn what their own role can be in a democracy.”

The Toronto Star has quickly become a model of transparency with its efforts to open up the newsroom to reader scrutiny. Last year, the paper’s managing editor Irene Gentle started seeing an uptick in complaints and harassment against the paper that corresponded to the skepticism south of the border against fake news. “She became frustrated by the fact that we know there is a lot of hard work behind our journalism that is being done by solid ethical principles,” says public editor Kathy English, “but readers weren’t getting that.”

Starting in May last year, the paper launched its own Trust Project, hiring a transparency reporter, Kenyon Wallace, whose beat is the newsroom; each week he picks a topic and interviews reporters about how they cover it. So far topics have included how the paper covers politics, how the science reporter vets scientific claims, and how the restaurant critic reviews new eateries. Back in January, Star reporters and editors participated in an Ask Me Anything (AMA) on Reddit, in which readers queried them on issues ranging from the paper’s corrections policies to how it covers outrageous candidates like Toronto’s late mayor Rob Ford.

That effort was driven by the younger journalists, says English, despite qualms by her and other veteran colleagues. “I didn’t know what to expect and whether there might be some ugly trolling—and there was a little bit,” she says. To keep the conversation civil, however, the paper had an experienced moderator approve comments and make sure questions didn’t get out of hand. The Star’s transparency efforts may be working; according to the Edelman Trust Barometer, trust of journalism rose 10 points in Canada over the past year, to 61 percent. While she says the Star can’t take complete credit for it, as one of the country’s biggest newspapers, it may have had something to do with it.

More outlets are experimenting with social media as a way to create communities for subscribers to interact directly with reporters and staff. The Dallas Morning News created a special Facebook group in September for subscribers only, where they can ask reporters and editors about decisions the paper has made; it’s now up to 1,400 members. “We wanted to get to know them and for them to get to know us as a way to overcome some of the mistrust that sometimes exists,” says engagement editor Hannah Wise.

Wise was worried initially that the group would be one big forum for complaints. But having discussions play out in public has given the paper a way to show it cares and correct misunderstandings. When one reader complained about not having his paper delivered, editor in chief Mike Wilson jumped in to make sure he got a replacement. When a headline was incorrect, some subscribers complained the paper didn’t have copyeditors anymore. “It was late at night, and I said, we do have copyeditors, they are still here right now trying to do work—you are welcome to meet them,” says Wise.

In other cases, admitting mistakes has led to more open dialogue. When a reporter was covering an issue of separation of church and state in a nearby suburb, she inadvertently used the word “crusade,” which readers pushed back on as an unfair use of a religious term. The reporter admitted that she hadn’t intended to use the word in that way, and would be more careful in the future. “Since then, the person who has given her the most grief has ‘liked’ every story she’s written,” Wise says.

In another case, some readers were upset by a weekend guide featuring a gay couple on the cover. Wise explained to the group that the paper’s role was to reflect the community, and not censor things some readers might not agree with. “We let the community have the discussion, and I was heartened to see that the majority of the group said, how can you say this about people who love each other?”

In addition to inviting readers virtually into the newsroom, some publications have even gone so far as to invite them in physically as well. City Bureau, a nonprofit news organization in Chicago, hosts a “public newsroom” every Thursday night, in which reporters offer talks and workshops on their investigative reporting processes and solicit public advice and contributions.

Matt DeRienzo took that a step further as Connecticut statewide editor for Digital First Media, opening up a “newsroom café” to the public that was part coffee shop, part community center, and part library where people could peruse the publication’s archives. “The Little League and the Garden Club would meet right inside our newsroom,” DeRienzo says. Over time, having community members in the newsroom resulted in giving journalists more sources and perspectives they could work into stories, adding more nuance and complexity.

As much as the online environment has eroded trust and created the need for more transparency, it also offers unique tools to increase transparency

At the same time the publication was physically inviting people into the newsroom, it was also aggressively soliciting feedback on the web through its corrections policy. Rather than just posting corrections when errors were made, the site included a box prominently placed on every story that asked the community to fact-check articles, and contact the reporter through a form if anything was incorrect. In addition to correcting errors, readers often wrote in with missing information and additional perspective that reporters sometimes worked into other stories. “People don’t assume you are open to that unless you tell them,” says DeRienzo, who is now executive director of Local Independent Online News (LION) Publishers. “It led to a lot more context and accuracy.” For publications considering increasing transparency, the decision takes forethought and planning. “It’s a lot of work and very resource-intensive,” says Wikimedia’s Kramer. She recommends publications think first about their reasons for wanting to be more transparent, whether it’s to acquire deeper sources, improve trust with readers, or create more engagement about local issues, and then choose the elements of transparency likely to further those goals. However it’s implemented, she says, the push has to come from the top, and be tied to clear performance goals for employees so they have an incentive to spend the extra effort. “It has to be something management supports and creates a structure for,” she says.

For journalists used to keeping their decisions on what to include and not include in stories to themselves, opening up what they do to such scrutiny can be disconcerting to say the least. “It makes journalists uncomfortable sometimes, because they feel like it is making them a part of the story rather than being able to hide what we do,” says the Democracy Fund’s Stearns. Journalists spend a lot of time and care crafting their stories to give them the proper balance and serve an interpreting function for the audiences—exposing processes and source material can be nerve-racking.

“Those fears are absolutely legitimate,” says Stearns. “It’s a scary thing, and I totally honor and respect that. The question for me is not should we do it or shouldn’t we, but when should we do it?” Just because a publication embraces transparency doesn’t mean that reporters have to post interviews and notes for every story. Publications should be strategic, say advocates, choosing stories to start that might be important or controversial, such as investigative stories or enterprise journalism exposing an issue of pressing local concern. “It may feel risky,” says Stearns, “but it will also make you unimpeachable.”

The year that “Putin’s Revenge” was broadcast was incorrect in an earlier version of the caption. The correct year is 2017, not 2012.

An earlier version of this article erroneously said that Kalyani Chadha helped with the experiments that Michael Koliska set up for his Ph.D. dissertation.