Students Allyson Morin and Eric Zulch, an inmate, at work in a UMass social justice journalism and mass incarceration class taught at the Hampshire County Jail and House of Correction in Northampton, Massachusetts

Journalism education can help create a bridge between those incarcerated and the world outside

“You are wildly irrelevant when you come to prison,” he says. “You’re nothing here and you’re nothing outside because you’ve become a memory of what you used to be. But when I’m writing and when I’m doing journalism, I take back the narrative.”

It’s a life and profession Lennon—who is serving 28 years to life for murder in Sing Sing Correctional Facility—had never anticipated when he ran the streets of New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, selling drugs and existing in a haze of money, guns, and cocaine. After his 2004 conviction for murder, his life took a turn when he was recommended to participate in the Attica Writer’s Workshop, a creative writing course, run by Hamilton College professor Doran Larson at Attica Correctional Facility, where Lennon previously served time.

Over six years, the workshop ignited a love of storytelling and a fundamental understanding for Lennon that he was in a unique position to tell the hidden stories within the mass incarceration system, shining a rare light on life behind bars. That spark in the classroom has led to a full-blown foray into journalism, with bylines in The New York Times, The Atlantic, an Esquire spread on mental illness, and a contributing writer title at The Marshall Project.

Journalism education can help create a bridge between those incarcerated and the world outside. For those incarcerated, the study of journalism can provide tangible skills, such as writing, critical thinking, social skills, and a foundation in ethics that are invaluable on the outside, regardless of profession. But, even more importantly, helping incarcerated men and women create works of journalism that lay bare their hidden world can generate more societal understanding of their experiences, aiding in their rehabilitation upon reentry to the outside world. And as an industry that has increasingly been criticized for becoming more out of touch with the class and racial divide in this country, tapping into these prison narratives will go a long way in highlighting a societal issue that has been neglected for far too long.

I first met Lennon in a small meeting room inside the maximum-security prison in Ossining, New York in March. A tall, muscular man with glasses and clad in a green prison-regulation uniform, tattoos snaking up his bicep, Lennon towered over me as we shook hands and moved to sit next to each other. A corrections officer quickly redirected him to an empty seat across the table. It was one of many subtle reminders that we were in a strictly controlled environment—one that traditionally is not conducive to journalism.

But Lennon has made the prison his personal newsroom, searching for rich characters among his fellow inmates, scouring newspaper articles for news pegs, conducting interviews in the prison rec yard, and reaching out to journalists on the outside for editorial direction and Freedom of Information Act requests to support the stories he comes across every day.

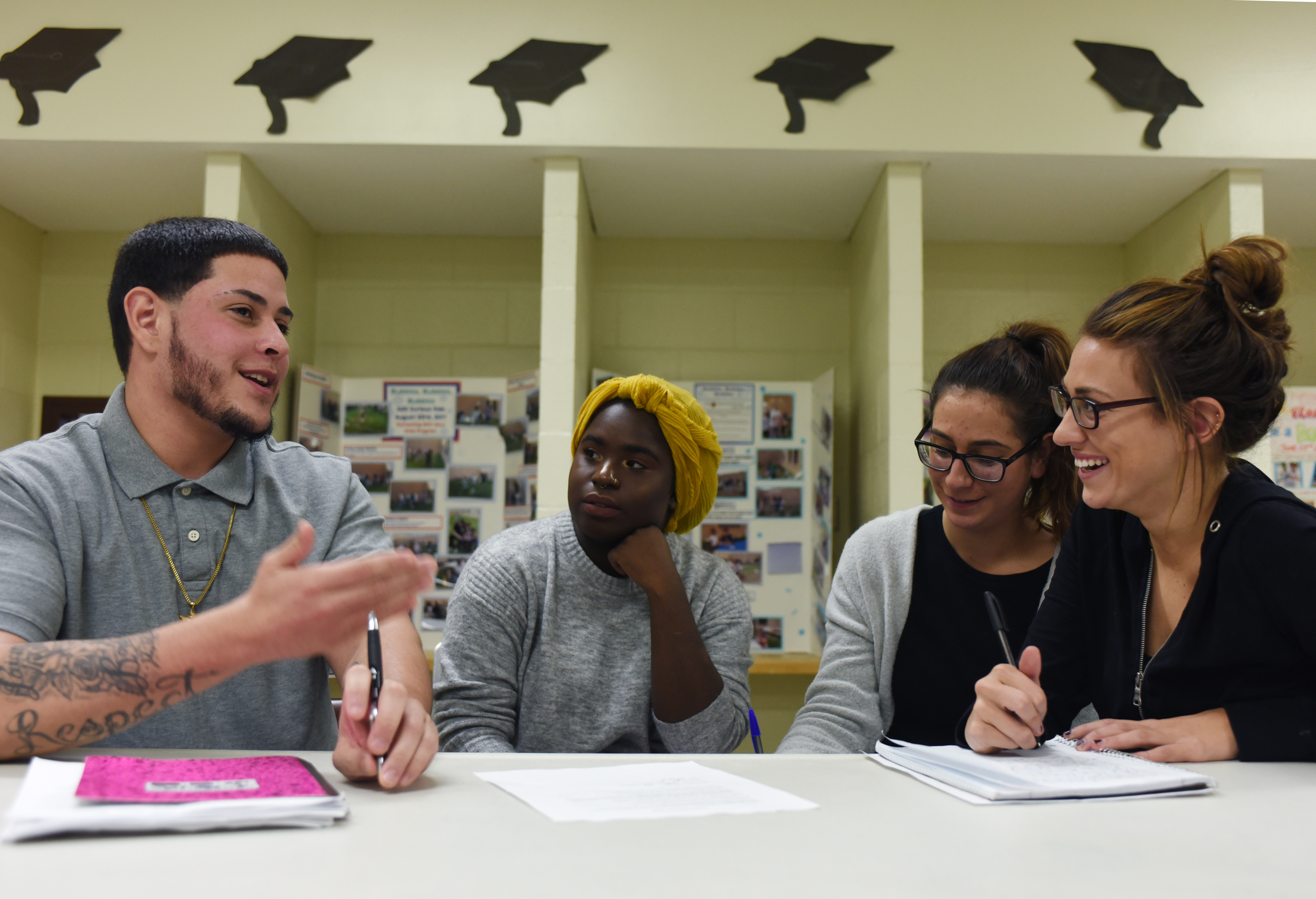

Students (from left) including inmate Josh Feliciano, Talya Sogoba, Danielle Haley, and Rhiannon Snide in the UMass social justice journalism and mass incarceration class taught at the Hampshire County Jail and House of Correction in Northampton, Massachusetts

“I’m not bound by the red tape you are,” he explains. “If I want to talk to a prisoner or an officer, I don’t have to get approval from an administrator, don’t have to have subjects sign waivers. With pen and paper in hand, I just talk to people and jot stuff down and write stories. This is my world.”

His first piece for The Atlantic was published in 2013 after months of constant revisions as he struggled to perfect his writing with little background and training in the craft. The piece made the case for stronger gun control, using his own crime as insight into the mind of “a gun-toting gangster.” It’s a style that has become his signature—part memoir, part investigative journalism.

Since then, Lennon has gained notice for his hard-hitting news commentaries and investigative pieces. A recent piece, based on almost a decade of reporting and personal observation, highlighted how security cameras installed in Attica tamed some of the abuses against inmates by corrections officers. Lennon says a journalism course behind bars would have made his journey into the field easier, but he hopes to continue his career as a journalist when he is eligible for parole in 2029.

Currently, Lennon is the exception, not the rule. For most men and women, incarceration is a period of lost time in an environment very few on the outside understand. Hundreds of thousands of prisoners a year are released with few tangible skill sets and the burden of both a record and trauma. They become the forgotten members of our society until they reoffend, as 76.7 percent of state prisoners and 44.9 percent of federal prisoners do within five years, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics and United States Sentencing Commission studies.

Society cannot make the best decisions about dealing with the effect of mass incarceration on communities without getting direct input from those living within the system

I started teaching journalism behind bars four years ago, first as a volunteer instructor and then as part of an immersive explanatory journalism course offered at a local jail that I created with my colleague, Razvan Sibii, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Since starting my work at the jail, I have often been asked why I spend my time sharing my 20 years of journalism experience and training with individuals who have committed crimes.

The answer is simple. In “The Elements of Journalism,” the seminal book used in journalism courses around the country, Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel write that the purpose of journalism is defined by “the function news plays in the lives of people.” In other words, journalism is there to provides citizens with the crucial information they need to make the best decisions for their individual communities and government to function well as an overall society.

In the U.S., mass incarceration has created one of the largest subcultures of our society, and it is also the most secretive. The American criminal justice system holds roughly 2.3 million people in state and federal prisons, juvenile correctional facilities, and local and Indian Country jails, according to a 2018 report by the Prison Policy Initiative. That is roughly the equivalent of the entire population of Botswana.

Once inside, incarcerated individuals disappear into a closely guarded system that outside journalists can only cover peripherally. Society cannot make the best decisions about dealing with the effect of mass incarceration on communities without getting direct input from those living within the system. In teaching inmates to write well and think critically in order to share their stories, journalists can uphold our mission, while also providing valuable educational skills that can be used for rehabilitation when incarcerated individuals are released.

Prison journalism, itself, has had a long history in the United States. The first prison newspaper, called Forlorn Hope, came out of a debtors’ prison in 1800. As incarceration grew following the Civil War, a reform and rehabilitation movement also emerged, resulting in more prison publications, including The Prison Mirror, a publication out of the Minnesota Correctional Facility-Stillwater, which has the distinction of being the oldest continuously published prison newspaper in the United States.

A return to a more punitive stance on mass incarceration in the United States over the last few decades, however, made it more difficult for prison newspapers to operate, further shrouding that world in secrecy. Many papers were either shut down by prison authorities, became increasingly censored or simply petered out, given fewer resources.

Wilbert Rideau, a former death row inmate who was editor of The Angolite—an award-winning prison magazine out of Louisiana’s Angola Prison—for over two decades, says it has become more challenging for prison reporters on their own today. He says his magazine was originally allowed to thrive because of a progressive warden and media attention from local and national outlets. A new prison administration, however, clamped down on the paper’s abilities to do the journalism it prided itself on and is reflective of how many prisons view journalism behind bars.

“Ours was a unique situation for a long time, one in which everything in the universe came together for us,” he says. “I doubt that it will ever happen again to lift the lid of censorship and extend journalistic freedom to prisoners.”

Since being released after 44 years in prison, Rideau has penned a memoir, called “In the Place of Justice: A Story of Punishment and Deliverance,” and continues to write and lecture about mass incarceration and prison journalism in the United States.

Shaheen Pasha (standing), an assistant professor of journalism at UMass Amherst, talking with students—inmate Dakota Micks, left, and Melissa Myers—in her class at the Hampshire County Jail and House of Correction in Northampton, Massachusetts

While the environment has definitely become more challenging, there is also renewed interest in mass incarceration, given the popularity of publications such as The Marshall Project and the success of Michelle Alexander’s book, “The New Jim Crow,” and director Ava DuVernay’s 2016 Oscar-nominated documentary, “13th.” Society is hungry for these stories and, in speaking with incarcerated men and women, the desire to produce those stories from within is also strong.

Working journalists, academics, and journalism schools can provide the training and support to help meet this demand if we’re willing to work with corrections officials.

The award-winning San Quentin News, which has had a solid relationship with the University of California-Berkeley, is one prominent program that has shown the value of teaching inmates journalism skills. Other prison-based academic programs have emerged as well, such as NYU’s Prison Education Program, my own social justice journalism and mass incarceration class at UMass Amherst taught at the Hampshire County Jail, and a new class set to launch with Emerson College, through the Emerson Prison Initiative which is modeled on the Bard Prison Initiative. The classes range from theoretical seminar courses to hands-on writing and reporting.

“Journalism is humanizing because it is about telling people’s stories,” says Bruce Western, professor of sociology at Harvard University and author of the new book, “Homeward,” which chronicles the lives of former inmates in their first year after release. “The whole concept of rehabilitation is about addressing and remedying deficits of schooling or social experiences and providing people with experiences that will fill their gaps in learning and job skills. There is a massive role for journalism in the prison system in training people to be writers and reporters.”

But what is needed is qualified instructors willing to invest their time training the prison population, as well as prison administrations that are willing to see the larger scale benefits of providing tangible, skill-based prison education programs that include journalism.

There can be resistance. Western says prisons in the United States are giant black boxes that are often difficult for outsiders to penetrate. Administrators are cognizant of the many risks associated with incarceration, from the safety of staff and inmates to overarching political risks, in which the mere appearance of being either overly progressive or overly restrictive can yield political backlash. As a result, many administrators are careful that the programs brought into the prison do not disrupt established routines or question authority.

Prison journalism has had a long history in the United States

In some cases, journalism can be seen as a security threat with writers facing intimidation for their work. Arthur Longworth, who is serving life without parole at the Monroe Correctional Complex in Washington state, knows this firsthand. He is a contributing writer at The Marshall Project and has published a loosely fictionalized book on prison life, called “Zek.” His award-winning piece, “How To Kill Someone,” was a reported memoir, in which he delved through his state files as a young man in the foster system.

But Longworth’s accolades have only landed him in hot water. His piece on an autistic prisoner was originally confiscated by authorities and banned. He spent time in solitary for his book, lost job and educational privileges, and was cut off from outside communication for “writing an article with no approval from the superintendent,” the Marshall Project reported, quoting the Department of Corrections.

Longworth says he feels an obligation to write because outside journalists rely heavily on the state narrative to tell the stories of those incarcerated, which tend to center around the crime, rather than the person who came before or their situation after incarceration. “There’s so much more you can’t know because you’re not living it,” he says. “I get in trouble for it here but, the way I see it, I’m 53 and I’ve lived every day of my adult life in prison. I keep writing because there is nothing more that prison can take away from me and maybe some of my work will help others.”

Longworth says that journalism education should be offered to provide inmates with an outlet for their stories and tangible skills they can use to improve themselves. But he says such classes would also go a long way in alleviating some of the distrust prison administration can have of journalism by showing how beneficial it can be to both the prison and society in general.

Prison education is, in fact, an important facet of rehabilitation. A 2013 study conducted by RAND Corporation found that inmates who participate in correctional education programs have a 43 percent lower chance of returning to prison than those who do not. From a cost perspective, RAND found that educational programs cost about $1,400 to $1,744 per inmate every year, which could save prisons between $8,700 and $9,700 per inmate due to lower levels of recidivism, a fairly conservative estimate of cost savings.

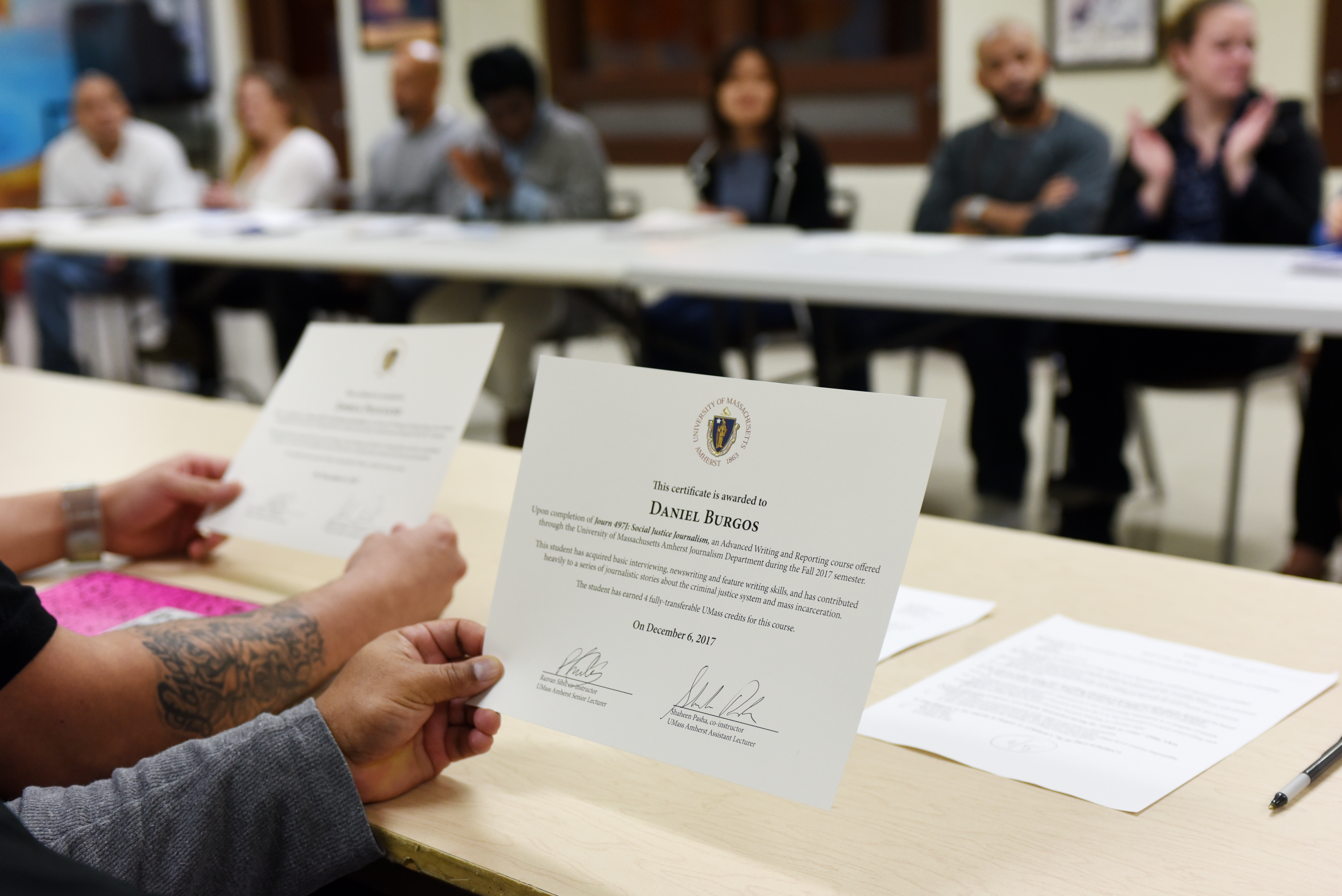

Inmate Daniel Burgos holds his certificate of competition on the last day of the class in December 2017

But prison education varies from state to state and, in some cases, focuses on activities to keep inmates busy—such as crocheting or bridge—rather than providing qualified instruction in areas that could actually benefit inmates upon release, according to a 2017 survey by advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

For those interested in teaching journalism, a straightforward reporting and writing class is one option. During the fall semester of 2017, my colleague Sibii and I created an immersive explanatory journalism class at the Hampshire County Jail and House of Correction in Northampton, Massachusetts. The experimental class brought 17 UMass students into the jail to work alongside 10 incarcerated students.

Our inside students learned the fundamentals of journalism—inverted pyramid, interviewing skills, different lead styles, and nut grafs—while the outside students were provided with a unique window into the challenges of reporting on the mass incarceration system in the United States. Both sets of students received four college credits upon passing the class. Weekly, the students came together in small groups at the jail, covering stories that were pitched by the jail students.

San Quentin State Prison is a good example of an institution that has found a balance between giving the inmates a voice and maintaining stability at the prison

“Being able to express myself in front of strangers and know that our ideas and lives mattered to people that aren’t inmates helped me to come to terms with who I am and what I represent,” says Luis Santiago, an incarcerated student in the class. “The class helped set the stage for me to have a voice and be heard without fear of being punished or judged. I feel like I can do more with myself when I get out.”

Story topics ranged from the unintended consequences of the Prison Rape Elimination Act to mental health to parenting behind bars. Jail students interviewed other inmates and jail personnel while UMass students typed up the interviews and conducted external interviews and research with expert sources and online data. (The jail, like so many carceral institutions, does not allow internet access and computers are limited.) All personnel and inmates interviewed were required to sign a media release form in front of a designated jail staffer to avoid any impropriety or intimidation.

Dakota Micks, a former student in the class, who was recently transferred from the jail to MCI-Cedar Junction in South Walpole, Massachusetts, says the experience improved his writing and allowed him to step out of his comfort zone by asking questions and trying different styles. He is currently working with me on a piece for publication that came out of class discussions, highlighting his struggles with drug addiction.

Yvonne Gittelson, education coordinator at the Hampshire County Jail, says the administration had to tread a careful line in providing the incarcerated students with educational support for the class while also maintaining the security and privacy of the staff and other inmates. In some cases, there was also concern that the students may have used some of the story topics as a means of pushing their own agendas against the jail. Jail administrators opted not to comment on those stories but didn’t prevent any of the students from continuing to report on them. In return, Sibii and I agreed that any interviews obtained from inside would be used as part of larger trend stories about mass incarceration rather than focusing solely on the activities at the jail.

“There was skepticism over some of the stories that the guys were working on,” Gittelson says. “But, in the end, we saw what the benefits were for the students. They really felt like their stories were relevant and that the class gave them a voice and made them feel heard. It was empowering.”

San Quentin State Prison is a good example of an institution that has found a balance between giving the inmates a voice and maintaining stability at the prison. The San Quentin News distributes over 30,000 copies a month to every prison in the California Department of Corrections & Rehabilitation and is widely seen as a model for prison journalism and innovation, through its administration’s willingness to engage in rehabilitative programming and educational opportunities. It is also the home of “Ear Hustle,” a podcast co-produced by prisoners in partnership with visual artist Nigel Poor, that shines a light on the lives of the men incarcerated in the prison. “Ear Hustle” was nominated for a Peabody Award in April and, along with the San Quentin News, has raised the profile of the prison and attracted funding for such initiatives from external sources.

Yukari Kane has been a volunteer instructor for San Quentin’s Journalism Guild—a group of inmates who train in the craft of journalism in order to freelance for the newspaper— since 2016. She serves as an academic advisor to the San Quentin News, along with UC-Berkeley professor William Drummond, who teaches a graduate class in editing that brings university students into the prison to edit and work with the prison news staff on their stories.

Kane says her class is aimed at instilling journalistic writing skills, news judgment, and teaching the inmates that their stories matter to the outside world. She adds that courting controversy is not the goal of the class or the newspaper, which focuses instead on covering news events and features within the prison and rewriting articles about the mass incarceration system from other news outlets, with additional original reporting, relevant to their reading audience at San Quentin and other institutions in California.

“Nothing has ever been censored while I’ve been here,” she says. “The guys are careful because they have so much to lose if the paper folds. They’re doing important stories, but nothing that they have done so far has warranted any censorship.”

Prison education is, in fact, an important facet of rehabilitation

Rahsaan Thomas, sports editor at San Quentin News, says the newspaper has published stories—such as one on prison conditions during an outbreak of legionnaires’ disease and another on a transgender correctional officer—that were considered controversial but were ultimately allowed to run. “We’re not TMZ and trying to sensationalize our experience here,” he says. “The old San Quentin News used to talk about riots and stabbings but we choose not to write about those things because we don’t want to create a situation where someone reads that and wants to retaliate. That’s not our purpose.”

“While there is a requirement that the newspaper goes through an administrative review, administration can’t censor the paper,” says Kristina Khokhobashvili, staff advisor to San Quentin News. “The paper has written plenty of articles that could be seen as negative and, maybe that’s bad from a PR perspective, but there’s nothing we can do about it. They have a right to have an inmate-produced newspaper and, as long as there are no articles that [create] security issues like how to build a weapon, they can publish it.”

In 2014, the San Quentin News won the James Madison Freedom of Information Award from the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ) for its coverage of a prison hunger strike, overcrowding, and the denial of compassionate release for a dying inmate. The entire staff are also members of SPJ.

Thomas, who is vice chair of San Quentin’s SPJ chapter and also writes for The Marshall Project, says the skills they have learned and the public notice their stories have received are opening up new career possibilities for those slated for release. “I used to think guns and money made me powerful but the pen is really what empowers me,” he says. “Writing and journalism allow me to educate the public and highlight the things that got me here and life inside. American society is hurting itself by over-incarceration. But providing these types of classes can allow society to repurpose what prison is there for.”

Students in the UMass social justice journalism and mass incarceration class in November 2017

It’s a model that other prisons in California are starting to consider. Adam Iscoe, a 22-year-old recent graduate of UC-Berkeley who took Drummond’s class, is now volunteering with inmates at California State Prison Solano in Vacaville to produce a newsletter, called the Solano Vision. The publication has become a passion project of the inmates despite a number of challenges, including lukewarm support from the administration, a lack of permanent space to produce the paper, and no journalism textbooks.

New York University’s Prison Education Program, which provides college programs for credit at Wallkill Correctional Facility in upstate New York, launched a Practical Journalism course in spring 2018, taught by Aaron Gell, former executive editor at Radar and current features editor at Task & Purpose. The journalism class aimed to give students basic journalism skills but also provide a wider understanding of media literacy.

Gell says journalists working with incarcerated students need to remember that they are being invited into a closed environment in order to provide students with the practical tools of journalism, such as writing and analysis. While journalism involves pushing boundaries and, in some cases, uncovering wrongdoing through breaking news stories, he says that a compromise has to be made in order to avoid putting the entire program at risk. “That’s hard for journalists to put their heads around because we’re so used to pushing back as hard as possible against authority,” he says. “But we have to curb that tendency and remember why we’re teaching there.”

Offering news literacy or journalism ethics courses is another way to bring journalism into the prison system. Jim Matesanz, a retired prison superintendent who now serves as the field and faculty coordinator for the Boston University Prison Education Program, says incarcerated individuals have been separated from society and teaching them how to analyze the news they consume can help them to separate fact from fiction when they reenter society. He adds incarcerated students would benefit from improving their skills in media literacy, ethics, and law as well as memoir writing, which can be therapeutic by allowing them to express themselves. Keeping those elements in mind when pitching a journalism class to prison administrators is a good strategy.

Uncovering these hidden aspects of society and providing an outlet for silenced voices is part of our mission as journalists

While there are clear benefits and models of successful prison journalism programs around the country, those interested must be aware of the challenges involved. It can take convincing to get prison administrators on board. In my own class, my partner Sibii and I had to not only prove the educational benefits of the class but we also had to prove that our intentions were sincere and we were not there to exploit the stories of the inmates or write an exposé to bring down the jail administration.

Once the trust was built, and we decided to involve the university, there was a lot of paperwork involved. We had to seek approvals from our university administration to provide four college credits to our jail students—that is not a common scenario—as well as creating memoranda of understanding between ourselves and the jail to make sure that we were all clear on how the class would be taught. We also had to create a student contract for both sets of students to make sure everyone understood the rules and repercussions.

And money can be an issue. We obtained internal grants for some of our expenses, such as transportation and books, and UMass Amherst waived the per-credit cost for the college credits of the jail students, which came out to roughly $15,000 for the 10 men.

But, in the end, it’s worth it. Mass incarceration has created a whole sub-universe within the United States that is almost impenetrable and, therefore, society is unable to understand what is happening behind the barbed wire and tall walls. Uncovering these hidden aspects of society and providing an outlet for silenced voices is part of our mission as journalists and providing the tools for those immersed in this world should be an extension of that mission.