The Eiffel Tower in Paris in a photo from "Recovered Memory: New York and Paris 1960-1980"

It once seemed to take a million moving parts to put out a newspaper—a real, printed-on-paper edition of, say, The New York Times, the Herald Tribune or Le Monde.

It was an overwhelmingly analog and artisanal process, born of great machines, hot metal, and great skill–not to mention thousands upon thousands of words and hundreds on hundreds of photographs. The two groups that put all this together—the craft people and the editorial people—worked together harmoniously for the most part, provided one did not invade the other’s turf, most notably in the composing room. To news people of the time it was widely and proudly held that they produced the equivalent of a small novel every single day—and all with technology that barely had changed since the invention of the rotary press.

"Recovered Memory: New York and Paris 1960-1980" by Frank Van Riper (Daylight Books)

I formally entered the news business in June, 1967, one week out of City College of New York, as an editorial trainee for the New York Daily News—having previously run copy and news-clerked on the New York Post and the old Herald Tribune. The Post job was a one-night-a-week affair while I was in school. I worked the lobster shift from 1am to 8am on Saturday morning with a couple of other copyboys, catering to the needs of a small group of reporters and editors who put out the first edition of that PM paper from a decrepit city room on 75 West St., at the foot of Manhattan.

Ed James, a mordant—and morbidly obese—black guy was the head of nightside copyboys. Ed also manned the switchboard in the center of the city room, where he sat on a rickety chair like a dark Buddha. Like everything else at the Post the switchboard was a relic from “The Front Page”—all wiry cables and jacks, that Ed deftly plugged in each time he had to direct a phone call to someone’s desk.

Among other things, Ed taught us how to monitor the clattering AP, UPI and other wire service teletypes just off the city room. At regular intervals through the night we would tear the stories from the machines and place them before Bob Spitzler, the night city editor. He, in turn, would read them and either spike them or hand them to reporters or rewrite men to fashion into stories for the first edition. [It seems odd today, but back then all that the reporters and editors had in front of them (besides ashtrays filled to overflowing) were manual typewriters—not internet-wired computers; black rotary phones—not smartphones tethered to the universe. News from the outside world came only from what they heard on the telephone, the police scanner, or from what we gave them from the wire room. This was before 24/7 cable TV—CNN, C-Span—any cable TV for that matter. Even if there were a TV in the newsroom (there wasn’t) all you’d get at that hour would have been test patterns or maybe a black and white horror film.]

But keeping everyone abreast of breaking events was just part of our job. In fact our most important job was the 2am and 7am food order. One of us would go around to everyone in the city room, asking what he (or occasionally she) wanted from the one-arm joint downstairs that everyone called “the Greek’s.” The 2am was fairly easy—mostly coffee and Danish, maybe a bagel. The 7am was more elaborate: eggs and bacon, sandwiches, etc. It took a while for the order to be cooked up, so the deal was that the copyboy could eat breakfast free as he waited in the diner.

One morning as I was scarfing down my free bacon and eggs, I saw from the corner of my eye what I thought was a fairly good-sized cat scurrying across the door of the Greek’s storeroom.

It wasn’t a cat.

In the 1960s, manual typewriters, rotary landline phones, greasy black copy pencils and hot metal type were the building blocks of newspapering and if some of the building blocks—the typewriters and the telephones, for example—were succeeded by computerized or digital replacements used by a new generation of reporters and editors, the other building blocks simply vanished in the new digital technology

And along with them the thousands of craft union jobs they once supported.

I already had inhaled the tangy smell of printer’s ink some years earlier editing my college newspaper and working late into the night in the tiny printing shop that we used in lower Manhattan. There, we callow newsies from CCNY worked side by side with a handful of journeymen printers in a Dickensian printing shop, first on East 4th St., later on 22nd, where the printers let us use the Ludlow machine to hand-set headlines and where we routinely handled type with them on makeup. It was only after I had joined the big dailies that I learned the hard rules of newspaper apartheid.

In that rigid world, no one—no one—except members of the printer’s union could lay so much as a finger on type as the next day’s paper was being made up in the composing room. To do so would risk a wildcat chapel meeting in which every printer would stop work and go to a room just off the composing room floor until management expressed sufficient contrition for the outrage.

But it could have been worse. Legendary newsman and editor Jim Bellows once touched the type one time too often in the composing room of the Detroit Free Press and somehow a whole page form was ”pied”—dropped into hundreds of pieces onto the composing room floor as the edition deadline loomed. Bellows learned his lesson.

Certainly the union rules reflected a stubborn pride in one’s designated job, but also, I think, it reflected a town and gown tension between largely college-educated editorial people and their blue-collar craft union colleagues (even if printers routinely earned more than many reporters and editors.)

And if union rules in the US seemed rigid, in Europe they were even more so.

“I remember once we accidentally left off a photo credit for a photographer and he had the right to something like a 1,000 franc ‘indemnity’ because we had broken the rules of the agreement with the photographers union. And that was real money back then,” said Neil Offen who in the early 1980s edited an English-language weekly in Paris.

“Another thing about unions in France, and this is the stuff [President] Macron is working on now and the unions are resisting: it used to be that you got six weeks of vacation from the moment you started [a job.] That meant, say, you could work a week and then take six paid weeks off.”

None of that mattered to me back then as I pinched myself realizing that I actually was working in a big city newsroom. The Post’s was a dump, to be sure, but there I was taking Pete Hamill’s dictation from Selma, Alabama as he covered the violent turmoil of the 1960s civil rights movement. Over at the Herald Tribune, the city room was cavernous but it had a boatload of talent to fill it, not least including Tom Wolfe and Jimmy Breslin.

You couldn’t ask for more visual contrast: Jimmy always looked like an unmade bed; Tom always wore an immaculate white suit. Yet each redefined what it was to be a reporter. Each wrote lyrically and in depth about people. Each was simply eloquent. I wanted to be like them.

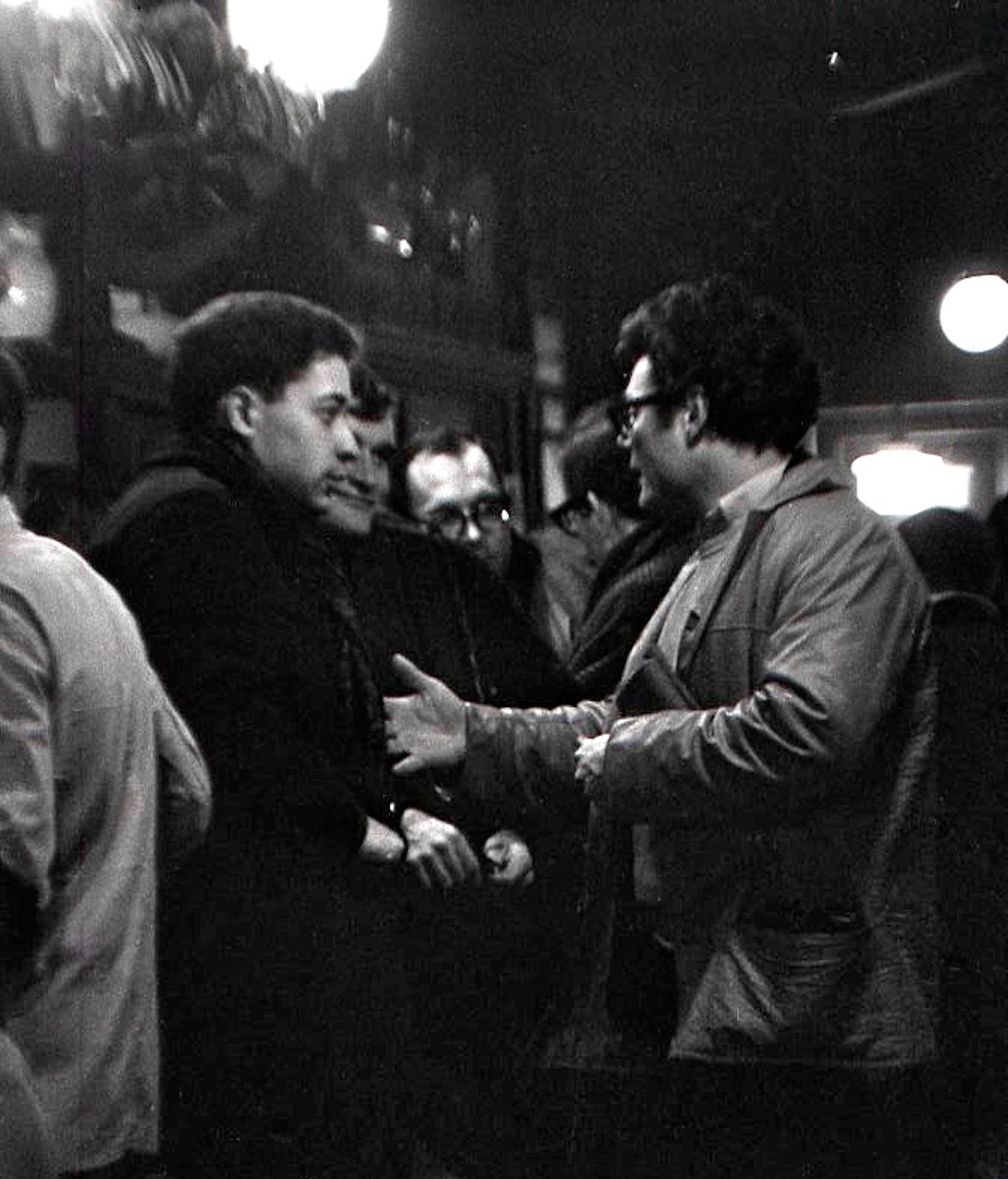

Years later, when I was in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau, Jimmy joined the paper, jumping from Newsday. I remember watching him in action at the Democratic convention in ’68, sticking to his sources like glue and following them until he got the story no one else had. In 1978 I was sent to coal country to cover a nationwide coal strike that seriously threatened the nation’s economy.

Having no way to cover it as a spot news story, I covered it the way I thought Jimmy Breslin might: doing feature stories on individuals, and larding my copy with lots and lots of color. It was some of the best stuff I ever did. But what I remember most is Jimmy calling me from New York early every morning (he got the name of whatever motel I was staying in from the telegraph desk) and asking whether he should come down.

“Sure, Jimmy,” I said, “there’s plenty of stuff to go around.”

“Nah,” he would say, “your stuff is too good.”

Jimmy never came.

In 1986 Breslin finally won the Pulitzer. I sent him a note congratulating him, and saying I always would be proud of the fact that I kept Jimmy Breslin out of coal country.

When people asked about my 20 years on the paper I said I would have paid the Daily News to write there—and I was not alone. Pete Hamill, who once wrote a thrice-weekly column for us, and later became editor-in-chief, put it best. Writing for the Daily News, he said, was like playing for the Basie band.