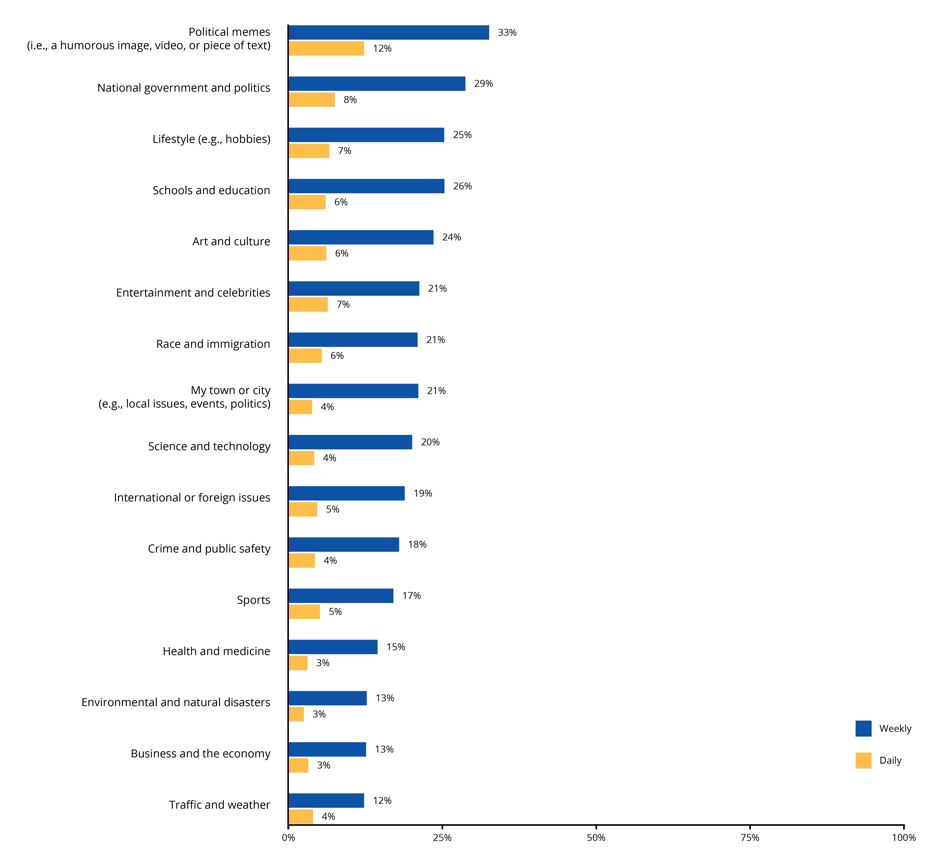

Several widely circulated memes were inspired by this photo of Angela Merkel and President Donald Trump at the G7 Summit in Quebec in June 2018. In a given week, most students (82 percent) surveyed had viewed a political meme, and many of them consider memes newsworthy on some level

They are not subscribing to newspapers. They are not watching television news. They seem to be on social media apps pretty much constantly, without much regard for the “grown-up” world of politics and policy. Perhaps, they are just, well, news-less.

Numerous stereotypes persist about young news consumers today in anxious discussions among news editors, professors, teachers, librarians—and parents, who secretly share worries about the fate of young adults growing up in a so-called “post-truth” era.

And yet, with more careful observation of what young adults actually do and how they think about news, the “grown-ups” could learn a lot—both about just how erroneous and short-sighted these stereotypes are, and what the future of news might look like.

Media companies are desperate to attract and lock in the next emerging demographic group, Generation Z, while holding on to the late tail of the millennial generation. For the news industry, it’s all the more urgent to see what can be learned from these always-on generations.

A research team that I was part of tried to do just that in our new report from Project Information Literacy (PIL), a national research institute that has been studying, for the past decade, how college students learn, find, and use information. We surveyed nearly 6,000 U.S. college students, across a wide variety of institutions, from the University of Alaska and the University of Texas to the University of Michigan and Wellesley College. We did follow-up telephone interviews, observed hundreds of our survey respondents on social media, and analyzed trends relating to a wider group of more than 130,000 young adults on Twitter.

Our study was conducted by PIL director and information scientist Alison J. Head, and co-researchers P. Takis Metaxas, a computer science professor at Wellesley College; PIL’s Margy MacMillan, a longtime librarian; and Dan Cohen, a technologist and the university librarian at Northeastern University, where I also work as a professor of journalism and media innovation. It was funded in part by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and a grant from the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL), the largest division of the American Library Association.

The findings from our study about young news consumers speak to a deep yearning for journalism to be better, but also a desire for more structure and integrity amid the online chaos young adults often perceive. Most survey respondents (82%) agreed that news was important in a democracy, while another three-fifths (63%) agreed that following the news is a civic responsibility. “Who would speak for the community and marginalized groups if the news wasn’t present?” one science major told us. “People should follow the news. They should know what is going on in the world.”

Students were generally unhappy with what they perceived to be increased bias in news reporting. While two-thirds (66%) of the respondents agreed with the statement that “journalists make mistakes but generally try to get their news stories correct,” many were still suspicious of news organizations that injected bias into stories solely for profit. As one student noted, “Their end goal is selling advertising.”

Further, there was a lot of uneasiness, even anger, about news seeming to pop up in all places, at all hours. Students doing lab work might be interrupted by mobile phone news alerts of missile tests in North Korea and by concerns about their own safety. News of President Trump’s latest tweet might suddenly dominate a social space. One female science major told us:

News interrupts my life a lot, especially when I’m on Facebook and I’m looking at friends’ pictures and enjoying myself, and then there’s videos about violence in Gaza and I think, “Oh God, I can’t avoid news!” I’ve read that news like this can desensitize us, and we have to compartmentalize all these images that are just thrown up on social media. I just wish there were more warnings or you could choose to view it or not.

Granted, generational technology habits fuel these disorienting dynamics. Almost half of the survey respondents (44%) said that, over the past week, they had accessed news on four or more social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or YouTube; nearly two-thirds (65%) said they got news on three or more social media platforms. Three-quarters of the respondents (76%) said they had received news from online newspaper sites in the past week.

While we heard genuine idealism about what news should be, there was disappointment among college students about what news currently is, and a lack of confidence, to some extent, about their own skills for navigating this world.

“Fake news,” no matter what agenda this phrase is pushing, has had an impact on news consumers. A third of the survey sample (36%) said they agreed that the threat of “fake news” had made them distrust the credibility of any news. Almost half (45%) struggled with discerning “real news” from “fake news,” and only 14% said they were “very confident” they could detect “fake news.” As one student lamented, “It is really hard to know what is real in today’s society. There are a lot of news sources, and it is difficult to trust any of them.”

There were also many complaints from young news consumers about all of the rabbit holes of misinformation and the troubles they face traversing a minefield of bias, lies, half-truths, and statements from politicians that purposely omit essential details. As one junior majoring in life and physical sciences summed it up, “I spend more time trying to find an unbiased site than I do reading the news I find.”

These young people are part of a generation that, as one interviewee put it, knows only “fast news,” a kind of baffling blur of disconnected and incomplete snippets and hot takes, tweets, GIFs, and memes that have come to be, in large part, a by-product of social media posts. As one film major said: “The speed of news is changing; it really has increased with the amount of news that’s out there … News stories happen and appear so quickly.”

News organizations increasingly seem to package everything as breaking news, as students pointed out, and half (51%) of the students we surveyed agreed it was difficult to identify the most important news stories on any given day. It is difficult to know, they indicated, how to respond to all of these constant, urgent calls for attention. When asked how they assess the credibility of breaking news before they share it—if at all—many students admitted not being particularly thorough.

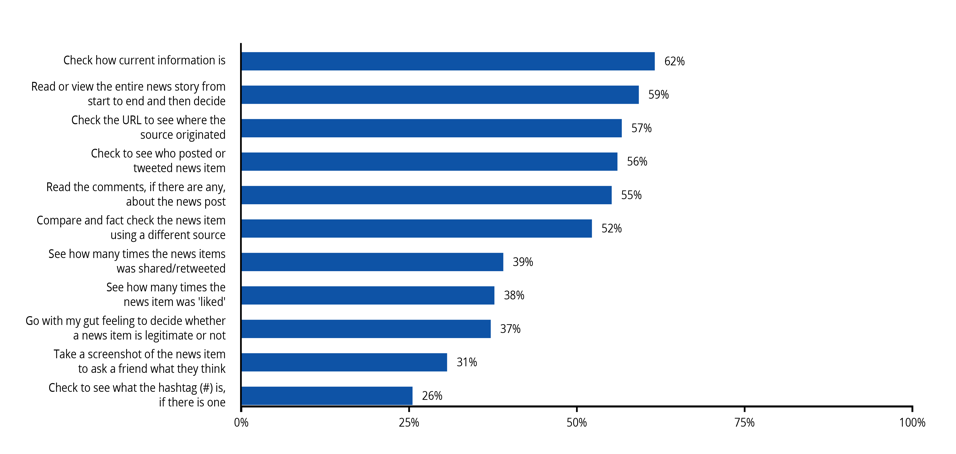

How students evaluate breaking news they share

A sample of 5,844 respondents returned an online survey administered at 11 U.S. colleges, universities, and community colleges during 2017 and 2018. On the questions represented in this chart, respondents were asked to choose among “always,” “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” and “never.” This graphic represents the percentage of persons answering “always,” “often,” or “sometimes,” which have been combined to produce an aggregate percentage.

A fraction of students were, admirably, “lateral readers,” who compared a news story from say, the HuffPost, with how that same story appeared in The New York Times or even Breitbart News. Yet we might find ways to train all students to be more diligent about credibility and evaluation. And instead of blame, we would be better to engage with parents, educators, news organizations, and social media companies about students gaining information competencies for navigating today’s difficult news terrain. Our report goes into some detail on these questions and provides recommendations.

At the same time, what also makes this generation different is their role in disseminating news and, in a sense, being creators of news, too. What we also wanted to know through our research is precisely why they share news.

College students often spoke to both a sense of community/social network stewardship and a desire to have agency in the public sphere. More than half (52%) said their reason for sharing news on social media was to let friends and followers know about something they should be aware of; nearly half (44%) said they agreed that sharing news gives them a voice about a larger cause. About one-third (32%) agreed that sharing news gives them an opportunity to change the views of their friends and followers.

The topics they shared news about varied widely, with many squarely in the “hard news” category. Silly listicles and cute cats were just one part of their world. Satire, funny memes, and humor in general provided welcome relief, for them, amid an unending stream of negative news. In the words of one political science major, “My grandmother, and most adults her age, think news is something very serious; she really doesn’t appreciate the humor as much as someone my age does.”

News topics students shared on social media during the past week

When asked about their sharing habits (based on different news topics) in the past week, respondents were asked to choose among “strongly agree,” “somewhat agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “somewhat disagree,” “strongly disagree,” or “I don’t share or retweet news items at all.” Responses of “strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” were combined into a single “agree” category to produce an aggregate percentage.

All of this data, and our report more generally, have implications today for news organizations, and social media companies, especially when thinking about engaging with younger news consumers.

First, products, stories, and strategies that provide “orienting” structures have a real appeal. News digests and other forms of media that organize and help provide context speak to a generation bewildered by the hybrid news-social media swamp they find themselves wading through. “A digest of top news stories is definitely in our formula of what makes a good news source,” a senior majoring in social and behavioral sciences explained, “since we often just feel so inundated with all the information that’s available on the web.” The success of viral publishers may have inadvertently created a deeper generational desire for some order alongside the digital churn.

Second, this generation consumes a great deal of visual media. Think Instagram and Snapchat. Of course, aligning with these tastes for the visual is a necessary strategy for media organizations. But here media might also recall the need for both orienting strategies and establishing credibility. Slick visuals may attract eyeballs, but they may hide nuance. News organizations that can authentically communicate what they don’t know, or what may remain uncertain, while balancing the need for graphics, videos, and pictures, may win the battle for both attention and trust.

Third, social media companies are often blamed for destroying the business model of news. What is probably underappreciated is the degree to which, by using machine-learning algorithms to serve up a very wide variety of content, social media companies muddle the very category of “professional news.” Quality news is mixed into a blender of other, lower-quality content, diluting trust and appreciation for quality; a sign of this is the way social platform companies, in their rhetoric, lump together the whole spectrum of news and information under the generic category of “public content.”

The chaotic stream of content served up by algorithms on social platforms has undoubtedly contributed to cynicism about news among young people. Finding ways to better tune algorithms for the purposes of serving up both high-quality and highly relevant news is crucial.

Finally, this is the first generation to see direct, personal engagement with the news as part of their world. Young news consumers have spent all of their lives so far with the full power of mass self-communication and with the speed, ease, wide choices, and socially optimized and shareable content afforded by contemporary social media.

For news organizations, these life experiences and their attendant expectations mean that providing more participatory opportunities and authentic engagement, both chances for contributions and critical feedback, is vital. It is a generation both yearning for a bit more order amid the chaos of news—but also for a real chance to help make the news better.