NPR reporter Asma Khalid, who covered demographics and the 2016 presidential campaign, during a live broadcast. In the run-up to the 2018 midterm elections, her beat has focused on the American voter

While reporting on the 2018 midterm elections in July, NPR reporter Asma Khalid went to Georgia to talk to African-American voters. Knowing she had been interviewing Republicans a few days before, “they wanted to know why they were still on board with Trump,” Khalid says. “It made me think how unfamiliar Americans are with one another. We all live in bubbles. It’s hugely important for us to understand our fellow Americans.”

Khalid also covered the 2016 presidential election, and her background and experience with voters in swing states like Virginia, Florida, and Ohio gave her unique insights into the role of race in the race. Before Trump was even the Republican nominee, she pitched a series on the anxieties of white voters to her editors at NPR and found some hesitation to look at the white population as having particular anxieties of its own. “It turned out to be one of the most powerful forces in the election,” she says. “But early on, it seemed like a very foreign concept. I would make the argument that it wouldn’t be that foreign if newsrooms were more diverse.”

Diversity is one of the issues media outlets are grappling with as the midterm elections approach. All 435 seats in the U. S. House of Representatives and 35 seats in the U. S. Senate will be contested. There will also be gubernatorial elections in 36 states.

Given the number of races in play, the midterms are difficult to cover even during the best of times

Multiple races are difficult to cover for many local newspapers, already spread very thin after years of layoffs. And there are signs that newsrooms have a long way to go before winning back audience trust. In a Pew Research Center survey taken in March 2017, 89 percent of Democrats agreed that criticism from news organizations keeps “political leaders from doing things that shouldn’t be done”; only 42 percent of Republicans shared that view. In a survey conducted in January and February 2016, nearly the same share of Democrats (74 percent) and Republicans (77 percent) supported that view.

Some newsrooms are addressing the challenges of the midterm elections by taking a more collaborative approach. Polling experts are exploring how to communicate uncertainty in a more meaningful way. New independent outlets are filling the space left by the decline of local newspapers. Dozens of news organizations are joining ProPublica to cover the complexities of the voting process. Reporters are increasingly aware of their role in the fight against misinformation. Here’s how some journalists and news organizations are trying to shape their election coverage in 2018.

Giving voters—and non-voters—a voice

Asma Khalid grew up in a very small town in Indiana, primarily a Republican state throughout its history. She is also a Muslim and a woman of color. “I grew up thinking, ‘If I’m going out and ask people what’s motivating them, they will treat me with an equal level of respect.’ What 2016 exposed to me is that this is not always true,” she says.

Khalid started covering politics in Massachusetts during the 2014 midterm elections. A year later, she joined NPR’s national political team to help cover the presidential campaign. She is still based in Boston, but she is constantly traveling. Her beat: American voters.

A crowd cheers as President Donald Trump arrives to speak during a rally at Wesbanco Arena, in Wheeling, W.Va. in September 2018. At NPR, Asma Khalid met with over 50 Republican voters across Ohio, Georgia, and West Virginia in order to assess the strength of the electoral coalition that had helped Trump to win in 2016

“Midterms are largely being fought in contested House districts that don’t look entirely like the full American electorate,” Khalid says. She has been in some of those districts to look at things like the effect of the Trump administration on his voters. Earlier this year, she met over 50 Republican voters across Ohio, Georgia, and West Virginia. Her goal was to assess the strength of the electoral coalition that had helped Trump to win in 2016.

In order to select the voters she should talk to, Khalid looked at the 2016 exit polls to drill down into the demographic groups with whom Trump had performed particularly well. Through her reporting in 2016, she had a solid sense of what traditional Republicans looked like and how they differed from Trump’s particular brand of the GOP base. “We focused on veterans, white working class, evangelicals, and traditional college-educated affluent white voters,” she says.

Only one person expressed any regrets about voting for Trump. “Everyone else had become a stronger supporter, mostly because of tax cuts and the Supreme Court,” Khalid says. “Trump’s base may be smaller than the one on the other side. But knowing that it’s energized is important because Republicans tend to have a stronger turnout in midterms.”

Throughout the summer, Khalid worked with her colleagues on a week-long series about non-voters. According to figures from the United States Elections Project, only 36.7 percent of eligible citizens cast ballots in the 2014 midterm elections, the smallest turnout since 1942. After spending some time looking at digital databases that include government records of who is registered to vote and who cast ballots in past elections as well as information from outside data sources, Khalid and her colleagues noticed that many non-voters were lower-income, lower-educated people of color and overwhelmingly young.

According to U.S. Census data reported by CIRCLE, a Tufts University initiative designed to provide authoritative research on the civic engagement of young Americans, 80.1 percent of people under 30 didn’t vote in 2014. Khalid and her colleagues wanted to tell their stories, so they went to Nevada’s First Congressional District, where less than 5 percent of people under 30 voted four years ago. There they found the influence of income and education but also another pattern: even among the young and low-income population, Hispanics and Haitians were less likely to vote than whites.

Diversity is one of the issues media outlets are grappling with as the midterm elections approach

“People assumed that Trump’s rhetoric would motivate Latinos to come out in record numbers in 2016 but it didn’t happen,” says Khalid. “One of the things I learned is that these people have never been engaged with the system. Their friends and their family don’t vote, and campaigns don’t pay attention to them. Telling the story of these people is important. We rarely focus on who doesn’t vote, and it really matters. There’s an argument to be made that public policy would look different if the entire American population voted.”

While reporting for this series, Khalid came across some discouraging figures. According to a survey conducted by CIRCLE, a majority of working-class young people don’t think voting is an effective way to change society, and nearly 20 percent don’t think they know enough to be able to vote.

How to report on polling

The need to capture the opinions of non-voters is one of the reasons The Associated Press has launched AP VoteCast, an evolution of the traditional exit poll.

The national exit poll has been a fixture in U.S. politics for more than four decades. The first one was conducted for CBS on Election Day in 1972. After leaving polling stations, thousands of voters are asked about the way they voted but also about demographic variables and important issues affecting their vote. Sample sizes typically range from 8,000 to 20,000 voters, though exit polls in 1986 and 1988 reached more than 50,000.

In November 2016, the exit poll was paid for by a consortium of news organizations and conducted by Edison Research. In 2018 ABC, CBS, CNN, and NBC are still paying for that poll. But AP, along with Fox News and other news organizations, will pay for a new survey coordinated by NORC, an independent, non-partisan research organization based at the University of Chicago.

The AP VoteCast will provide data about all states with statewide races. The national survey will represent voters in all 50 states. NORC expects to conduct more than 85,000 interviews with voters, four times more than the 19,000 conducted by Edison Research in 2014. The survey will combine interviews on Election Day with others conducted online and by phone in the four days before Election Day.

Researchers behind the new survey say that the U.S. electorate is much more diverse than a few decades ago. Its voting habits have changed, too. Around 95 percent of voters cast their ballots in person on Election Day when Nixon was re-elected in 1972. Less than 60 percent did so in 2016. “The exit poll hasn’t kept up with these changes and hasn’t evolved to reflect the realities of modern America,” says Trevor Tompson, vice president for public affairs research at NORC.

NORC researchers have made major changes in the way they sample voters. Their goal is to better capture Latinos, pockets of people in rural areas, and suburban and ex-urban voters. The core of their survey is a probability sample of voters drawn from voter files. Those databases include key information that will help them draw more representative samples.

NORC tested this approach in 2017 during statewide elections in Virginia, New Jersey, and Alabama and was pleased with the results. By interviewing people over a few days and not just on Election Day, the researchers are trying to tackle one of the main challenges every pollster faces: fewer people respond to their calls. “We’re allowing people more opportunities to participate how, when, and where they want and in the language and setting in which they prefer to respond,” says Tompson. “We’re also able to capture the opinions of non-voters and understand how their views may differ from voters.”

The presidential election of 2016 was not a good year for forecasting

The presidential election of 2016 was not a good year for forecasting. Shortly before the election, the predictions of every high-profile outlet from The New York Times to FiveThirtyEight placed Clinton’s likelihood of winning the presidency at 71.4 percent or greater. “However well-intentioned these predictions may have been, they helped crystallize the belief that Clinton was a shoo-in for president, with unknown consequences for turnout. As the 2016 election proved, [these models] can be a fraught exercise, and the net benefit to the country is unclear,” said a report published in 2017 by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR).

One of the experts involved in the AAPOR’s report was Scott Clement, a member of the association and The Washington Post’s polling editor. His newspaper has never published an election forecast—and won’t this time, either. “We thought high-quality surveys gauging voters’ attitudes are the best focus for us,” Clement says. “These rigorous surveys are our most accurate gauge of candidate support. They also indicate how different demographic and political groups are dividing in their support, whether these divisions are smaller or larger than in the past three decades of Washington Post-ABC News polling, and what’s driving those differences.”

Other outlets are reconsidering forecasting models, too. Neither the Princeton Election Consortium nor The Huffington Post have published one for 2018. The New York Times has no current plans to publish a forecasting model for the midterms, according to a spokesperson for the newspaper, which did publish election forecasting models in 2014 and 2016.

Not every news organization is retreating from election forecasting, though. In May, The Economist published a model predicting which party will control the U.S. House of Representatives. “We both use more variables than other models and we address how national and local factors combine in a more sophisticated fashion,” says its author, data editor Dan Rosenheck.

Rosenheck’s methodology is based on three things. The first one is a forecast of the national popular vote based on indicators like special-election results and polling on the generic ballot, a poll question that asks voters whether they’ll vote for Democrats or Republicans for Congress. The others are a calculation of the vote share for every district based both on district-specific factors and candidate fundraising, and 10,000 simulations, each time randomly picking one plausible value for the national popular vote and 435 specific results for each district based on that vote.

Covering politics in Nevada

A week before the 2016 presidential election, Jon Ralston, an expert on Nevada politics, surprised many pollsters by calling the state—correctly—for Hillary Clinton. In a year marked by the failure of other predictions, Ralston insisted he got his forecast right by looking at turnout patterns in a state where most of the people vote before Election Day.

On January 17, 2017, Ralston and a few colleagues tried to capitalize on this expertise by launching The Nevada Independent, a nonprofit news organization focused on covering politics and public policy across the state. One of their first pieces was an article fact-checking the last State of the State address of Republican Governor Brian Sandoval. The Nevada Independent is providing nonpartisan coverage of the midterm elections. Its site has no advertising, no autoplay videos, and no paywall.

Balloons fall around Democratic candidate for U.S House of Representatives Ayanna Pressley at her primary election night rally in Boston in September 2018. Polls have been notoriously wrong in several states in recent years, including this year in Massachusetts, where candidate Pressley won the Democratic primary by 17 points despite polls predicting she would lose to incumbent Mike Capuano by more than a dozen points

The newspaper has five full-time reporters, two editors, and one associate editor. It has more reporters in Carson City, the state capital, than any other news outlet in the state. Its annual budget is $1.6 million. Around 9 percent of those costs are covered by sustaining members: 576 people who donate every month. The rest is covered by revenue from sponsored events and from the more than 1,500 personal and corporate donors who have contributed to the project since its launch. The donors are public and the newspaper mentions when a person in a news article is also a donor.

Midterm elections are especially important in Nevada this year. There is a competitive race to succeed Sandoval as governor and Republican Senator Dean Heller could be ousted by U.S. Representative Jacky Rosen, his Democratic rival. There are also two close congressional races and six measures on the ballot, including one that would require that 50 percent of the energy in the state come from renewable sources by 2030.

In a state where elections are close and difficult to forecast, polling is one of the obsessions of the newspaper. In late August, Ralston wrote a piece saying that they would only publish the results of a poll if they had full access to the data behind it.

State polls were notoriously wrong in 2016 in states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. They also failed more recently in Massachusetts, where candidate Ayanna Pressley won the Democratic primary by 17 points after the last poll before the election forecast she would lose to incumbent Mike Capuano by 13 points.

“If we had the budget, we would do a poll every 30 days,” says Nevada Independent managing editor Elizabeth Thompson. “What we do is digging into the polls of other outlets, evaluating them and comparing what they say with voter registration data. When reporting on polls, we try to let our readers know what to take away from them.”

The Nevada Independent has published thorough explainers on every measure on the ballot, summarized them in short videos, and organized a public forum on one of the measures with two speakers debating its pros and cons.

According to data from the U.S. Census analyzed by the Pew Research Center in 2016, 28 percent of Nevada’s population is Hispanic. Most of them live in the Las Vegas metro area and they represent 17 percent of the people eligible to vote.

Around two-thirds of the Hispanics who live in Nevada speak Spanish at home. This convinced the founders of The Nevada Independent that they needed to translate some of their articles and offer original content in Spanish. By the time they launched, they decided to translate at least two stories a week and hired bilingual editor Luz Gray, who covers politics and immigration.

Reporting on the voting process

A few months before the 2016 presidential election, New York-based nonprofit ProPublica organized a meeting with a group of reporters, editors, and technologists at CUNY’s Graduate School of Journalism in Manhattan. The meeting helped shape Electionland, a large collaborative effort to cover voting access, cybersecurity, and election integrity. Electionland brought together 1,100 journalists, among them 600 students from 14 universities and 400 local reporters working for 250 news organizations from every state but Hawaii. About 100 reporters worked at the newsroom set up at CUNY on election night.

Voting problems typically have been covered as a second-day story. “This project offers the chance to cover them in real time so that journalists can point to specific problems and public officials can sort them out before it’s too late,” says María Sánchez Díez, who works at ProPublica as the partner manager of Electionland.

Voting problems typically have been covered as a second-day story

Electionland had a small but meaningful impact in 2016. Thanks to its coverage, New York restored access to its elections hotline during early voting and two Hispanic women who had been denied the ability to vote were able to cast their ballots. The project also won several awards.

One of ProPublica’s partners back then was Matt Dempsey, the data editor for the Houston Chronicle. As early voting began in the state, he got a tip from Electionland, which received reports that there were signs in one of the Houston counties saying that voters needed IDs to vote. “This was one of the main issues in 2016, and will also be a key issue in 2018,” says Dempsey. “A law was passed in 2016 requiring voter IDs to vote but a court ruling reversed that law. Counties were specifically told by the judges not to ask for IDs but some did it anyway, which caused all sorts of confusion. Thanks to Electionland, I could send a reporter to a particular place to check this out.”

Dempsey is one of the local partners of Electionland in 2018. As of late this month, ProPublica had signed up 170 journalists working for 100 media partners from 44 states.

This time ProPublica’s goal with Electionland is to be smaller and sharper. Its editors have assigned two fellows and two experienced journalists: election reporter Jessica Huseman and developer and reporter Ken Schwencke. They are recruiting partners in states like Kansas, Florida, North Carolina, and Texas, which have a record of voting disputes.

They are also actively reaching out to women and people of color. “It’s very important that we are vigilant, intentional, and active about recruiting diverse journalists because communities of color, immigrants, black voters, and native voters are more likely to experience the problems the coalition is reporting about,” Sánchez says.

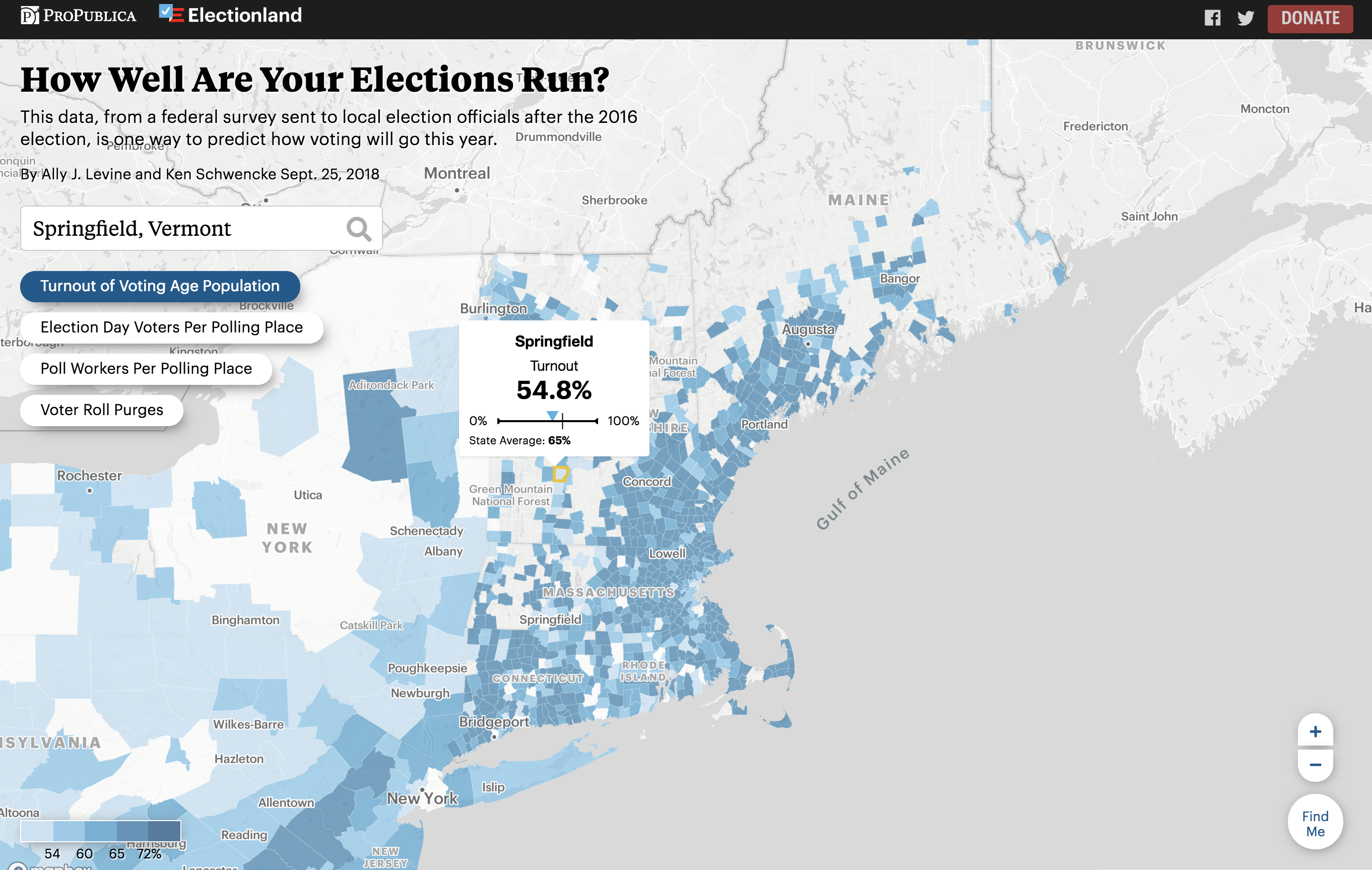

With ProPublica’s Electionland data tool “How Well Are Your Elections Run?,” voters can compare voter turnout in their county to others within their state or around the nation

Audiences can send Electionland tips about voting problems through several crowdsourcing tools: a web form, text message, a WhatsApp number, and a Facebook Messenger bot.

Electionland will also have access to the database of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights under Law, a nonpartisan organization founded in 1963. In every election, the committee staffs a call center with lawyers so anyone can call to get advice about voting problems in real time. In the 2016 election the committee received around 60,000 calls. “For every one of the calls they receive, lawyers write a small report with the name of the caller, the nature of the problem, and where it happened,” says Sánchez. “So we’ll have access to these reports and we’ll be able to detect in real time whether there are problems in a particular place. That will allow us to call newsrooms in that area, so they can send a reporter or call their sources.”

Every Electionland partner has access to two resources. The first one is a data tool called “How Well Are Your Elections Run?”, where anyone can find things like how their county’s turnout compares to other counties within the same state or what percentage of the population was purged from voter rolls. “Those indicators can serve as a starting point for interesting local stories with some additional reporting from partners,” says Sánchez, who points to a story published by Minnesota Public Radio about the long lines in a particular county as an example of what could be done.

The second tool is a Google Chrome and Firefox extension called the Political Ad Collector. This is how it works: every time you connect with Facebook, the extension sends to ProPublica every political ad you’ve seen. The database respects the user’s privacy. ProPublica doesn’t collect any personally identifiable information and doesn’t learn which ads are shown to which user. The database is public but Electionland’s partners have access to special features like the ability to search ads by congressional district.

An interactive site built by ProPublica allows anyone to see which ads different people are seeing on Facebook’s News Feed, depending on their age, gender, home state, and political views. A web page highlights the most intriguing tidbits journalists have noticed during their research.

Reporters from ProPublica have used the tool to locate political ads that were actually scams and malware and others that were ignoring federal election rules by not disclosing who paid for them. They’ve also discovered how someone created a fake Facebook page for special counsel Robert Mueller with more than 100,000 followers.

ProPublica emphasizes how important it is for journalists to avoid any kind of hyperbole while covering voting issues

ProPublica emphasizes how important it is for journalists to avoid any kind of hyperbole while covering voting issues. “It’s difficult to separate a real problem from something that is not so important and can have a negative impact and deter people from voting, so we need to be really responsible,” says Sánchez. “We must be careful not to undermine the trust of the people in the election process.”

MIT political science professor Charles Stewart III is one of the academics who developed Pew’s Elections Performance Index, which measures how well elections are run in every state. Stewart has some advice for reporters covering the midterms: “Do a better job at trying to explain the process of voting and actually show how it’s done. There are things to be shown in election administration that are very critical in giving readers or viewers a fuller understanding of what’s happening. For example, the logic and accuracy testing of voting machines and how it’s done, or even the counting process and how that happens.”

There’s also value in journalists discussing what’s happening on election night when numbers are being reported, especially now that some politicians openly question the integrity of the process. “It would be useful that journalists explain when different kinds of ballots are being counted or which votes are counted first,” says Stewart. “I know newspapers are spread very thin but to have someone dedicated to cover those processes would be a good thing.”

When writing about cybersecurity, Stewart urges reporters to distinguish between three different elements: voting machines, voter registration systems, and systems used to report the election results. Voting machines are less vulnerable because they are not on the internet. The other two elements are much more problematic because they are on some kind of network and could be exposed to intrusions and denial of service attacks.

Stewart warns that we are more likely to see problems in small jurisdictions. “Every state is doing something to shore up security,” he says. “The challenge is that once you move out of every state capital, you are moving from an organization with a lot of resources to an agency that may or may not have a lot of capacity. If you are a bad guy, you’ll be trying to find the weakest link.”

How to report on misinformation

The fight against misinformation will be one of the most difficult challenges of the midterms. Both Politico and The New York Times have asked readers to send them false political content intentionally created or distributed to deceive or misinform. So far Politico has debunked false stories about Representative Maxine Waters, a group of bikers riding to D.C. to support Brett Kavanaugh, and Malia Obama. The New York Times has debunked five viral rumors about the women who accused Brett Kavanaugh of sexual assault. Its podcast The Daily devoted one of its episodes to debunk a fringe conspiracy theory embraced by some of President Trump’s supporters.

The fight against misinformation will be one of the most difficult challenges of the midterms

When confronting certain types of misinformation, media researchers Joan Donovan and danah boyd have encouraged news organizations to embrace what they call “strategic silence,” a conscious decision not to amplify extremist views. Both Donovan and boyd are senior researchers at Data & Society, a research institute focused on the social and cultural issues arising from technological change.

“Newsrooms must understand that even with the best of intentions, they can find themselves being used by extremists,” Donovan and boyd wrote in a piece published in June by The Guardian. “All Americans have the right to speak their minds, but not every person deserves to have their opinions amplified, particularly when their goals are to sow violence, hatred and chaos.”

The article explains how Catholic, Jewish, and African-American newspapers engaged in strategic silence when covering the Ku Klux Klan in the early 20th century. According to Felix Harcourt, professor of history at Austin College, coverage by other newspapers, though negative, helped the organization: thousands of people joined the Ku Klux Klan after reading an exposé published in 1921 by The New York World. As The Verge’s Silcon Valley editor Casey Newton pointed out recently, the quarantine Donovan and boyd propose would be difficult to achieve and would require “a level of cooperation … that the national media has rarely shown.”

In May, Data & Society published “The Oxygen of Amplification,” a report arguing that journalists should think twice before mentioning falsehoods and manipulations designed to attract the media’s attention and multiply their reach. “Journalists are not just part of the game. They are the trophy. They should always ask themselves how they are being used, where they fit in the story, and how they could minimize harm,” says Whitney Phillips, author of the report and assistant professor in communications, culture and digital technologies at Syracuse University.

With the failures of 2016 coverage still fresh in mind, newsrooms, “feel a strong obligation to cut through the hyperbole and explain to … voters in simple language what’s at stake”

Phillips’s report includes dozens of recommendations on how to report on extremists, antagonists, and manipulators online. Avoid false equivalence when reporting on hatemongers and don’t let them explain their own motivations, she suggests, even if those kinds of stories get a lot of clicks. She also encourages reporters to avoid the word “troll”: “The term is too imprecise. By using it, it’s very easy to move into the mindset that these behaviors have no real consequences.” Before reporting on a hoax or a harassment campaign, Phillips says, ask whether a falsehood has reached a tipping point; debunking a rumor or a conspiracy theory that hasn’t gone viral can be counterproductive.

Given the number of races in play, the midterms are difficult to cover even during the best of times. But with the failures of 2016 coverage still fresh in mind, newsrooms, as the Nevada Independent’s Thompson puts it, “feel a strong obligation to cut through the hyperbole and explain to … voters in simple language what’s at stake.”