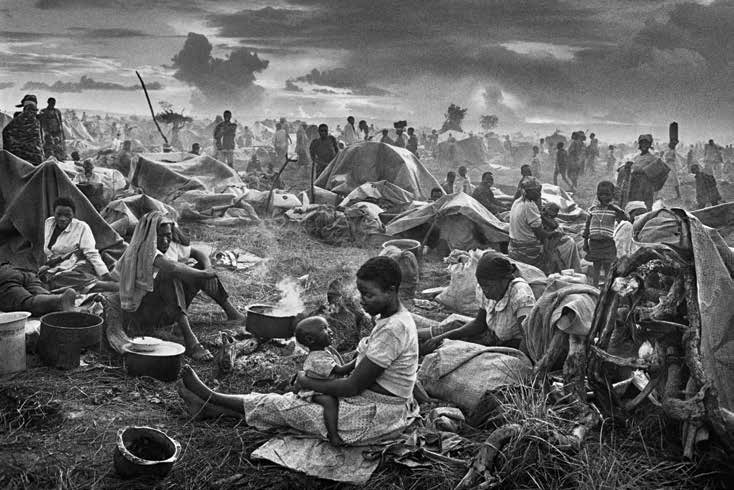

Rwandan refugees pictured at a refugee camp in Benako, Tanzania in 1994

In his book “Shooting War” (Glitterati Editions), psychiatrist Anthony Feinstein profiles 18 conflict photographers, providing insights not only into their work, but their psyches. Feinstein’s essays, drafted from his interviews with the photojournalists as well as their close friends and family members, reveal the experiences and traumas—along with the motivations, resiliency, mental health struggles, and personal hardships—that have shaped those behind the camera. What follows is an excerpt from Feinstein’s chapter on Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado:

Sebastião Salgado’s answers to my questions have a lot in common with his photographs. There is a depth to both, the richness of his images with their subtle gradations of shadow and light paralleled by his nuanced and carefully shaped replies.

"Shooting War: 18 Profiles of Conflict Photographers" by Anthony Feinstein

Long before Syrian refugees by the thousands began putting their faith in callous human traffickers to deliver them to a safer, ambivalent Europe, Salgado published a book called Migrations, documenting the movement of people across the globe. There is one photograph in particular that I want him to talk about, a touching image of a mother and child taken in a refugee camp in Tanzania. But before we can get to the specifics of the image, Salgado begins with the bigger picture of why he became interested in migrations and how he found his way to Tanzania and regions beyond.

A photographer known to spend years on a project exploring a single theme, he makes clear in conversation that his interests, while sparked initially by curiosity, are developed patiently over time, giving his body of work a unity that spans his four decades in the field. His Migrations project did not arise de novo, and to appreciate its depth—its lineage, as it were—one cannot parachute in by starting a discussion on a single photograph, no matter how powerful the image. The groundwork has to be laid first.

Salgado, who is Brazilian, starts with a historical synopsis linking his country to Africa. From there, he moves on to divulging that he once trained as an economist and, as an advisor to the World Bank in the 1970s, traveled a lot to Africa, bringing him into contact with postcolonial governments in Mozambique and Angola. From this vantage point, he was, in a preglobalization era, witness to market forces that were not only driving rural populations into the cities but also exploiting their labor in the process.

Along the way Salgado abandoned his career as an economist for photography upon realizing that with his camera he could communicate with images. It was a language that didn’t need translation.

He started photographing the plight of workers, helpless pawns in this toxic power play of competing monetary, strategic, and ideological interests.

Six years were devoted to this project, which he called Workers. And it was from his observations of workers on the move that his next project, focusing on migrations, was conceived.

Salgado is very clear in stating that he has never been a war journalist. His interest lay in photographing the movement of displaced populations, but in pursuit of this he frequently found conflict. This conflict was often very brutal.

In 1994, the year the UN brokered a peace accord in Mozambique allowing thousands of refugees to return home, genocide began in Rwanda. Vast numbers of Rwandans were again on the move, fleeing south into Tanzania and west into the Congo, where refugee camps in Goma soon held two million people. Salgado followed these migrating masses with his camera.

Which brings us back to the photograph that kicked off our whole discussion. It was taken in Benako, a refugee camp in Tanzania that had swelled to 350,000 people within four days. At first glance, the sight is all too familiar, the content generic to the theme of displacement: downcast, listless people crowded together out in the open under a dark, threatening sky with nothing to do but wait helplessly; scant shelter provided by the odd makeshift tent or a blanket slung over a pole; meager possessions scattered on the ground. It is a picture of profound despair. Until we look more closely.

What sets this image apart is not Salgado’s signature skill in using the light or his aesthetic framing of subjects. Rather it is the sight of an infant, center front, sitting on her mother’s lap gazing up in adoration, her shining face so poignantly at odds with the desolation that surrounds her. Too young to appreciate the gravity of her situation, we see in this child’s innocent loving look the promise of what life should hold for her, which is now imperiled.

In 1997 Salgado returned to Rwanda and the Congolese refugee camps of Goma that housed so many Rwandans. The refugees were being encouraged to return home. A quarter of a million people, still fearing for their lives, refused and disappeared into the rain forests of the Congo. Six months later, the remnants of this group began emerging near Kisangani, five hundred kilometers to the west of Goma. Only forty thousand had survived the journey.

Salgado arrived in Kisangani with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). He found a desperate situation. The refugees were exhausted; many were ill, and there were no medicines. At the nearby village of Biaro, one thousand surviving orphans had been lined up alongside the railway tracks and told to wait for food that never arrived. Around them were the dead and the dying.

While Salgado’s photographs are overwhelmingly a testimony to the suffering endured by those displaced by war, they also capture resilience among the survivors and their remarkable ability to adapt, no matter how desperate their situation. We see amid the hell of Goma and Kisangani signs of entrepreneurship and that innate human desire for some semblance of dignity. A moneyman exchanges currency; a barber cuts hair. This astounding capacity of mankind to adapt is a behavior that Salgado believes is universal.

Dire circumstances, however, do have a threshold beyond which even the strongest are challenged. As the Congolese government began forcing the bedraggled remnants of the flight to Kisangani back into the forest, in Salgado’s words, “the people became crazy.” Their distress in the face of force majeure counted for little. When eight hundred thousand people have been killed in three months and thousands more are dying each day from disease, the cries and shouts of the disposed are little more than faint accompaniment to the total collapse of moral order.

Salgado, who always works alone, lived among the refugees in Kisangani even after the UN personnel had left. There was no security. One day the director of a primary school came and told him to leave. He had heard that Salgado was to be killed for his cameras and clothes. There was little time to lose. That night, the director’s son would take Salgado by bicycle to the UN compound thirty-five kilometers away. A friend of the son, who also owned a bicycle, would accompany them, bringing Salgado’s possessions. Such was the seriousness of the threat that neither the son nor his friend was informed of the plan until just before the moment of departure, lest they talk and divulge their intent. At 3:00 a.m. the trio set off, reaching the safety of the UN by 7:00 a.m. The boys were overjoyed with the one hundred dollars each was given for saving the photographer’s life.

Salgado’s work photographing the migrations of Rwandan refugees left him physically and emotionally drained. “I was sick,” he told me. “I was not well. I had lost faith in our species. We are too violent.”

His immune system, compromised by stress, gave way, and he came down with a series of infections. An abscess had to be drained. His doctor, alarmed by what he saw, told Salgado that his body was dying and urged him to take a break. Heeding the advice, Salgado, accompanied by his wife, spent three months recuperating in a small village in Brazil.

During this period, Salgado had time to reflect on what he had witnessed. He remembers feeling despair, and his dreams were troubled, but there were no abiding symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Rather, what he experienced was a pervasive sense of sadness coupled with a conviction that mankind had lost its way. With his health improved, Salgado began a new project that broke with photography. He returned with his wife and family to his parents’ farm in Brazil, which he had inherited, a land that during his childhood had been verdant and lush but which over the years had been destroyed by deforestation and drought.

Salgado’s philosophy in life has much in common with biocentrism, an ethical belief that asserts the nonhuman value in nature. To him, the destruction of human life that he had witnessed, never more brutal than in Rwanda and the Congo—but in other insidious ways no less cruel elsewhere—was mirrored by violence inflicted on the land and the ruination of the environment. But whereas his photographs could not reverse the tide of human misery, when it came to land that had, to use his description, “been completely violated,” he could act.

His wife Léila suggested they replant the rain forest, which is what they did, planting hundreds of thousands of trees—all local—the species native to the region. Many did not survive at first, so they planted more, and with each successive planting the health of the land improved, the bird and animal life began returning, and a lost ecosystem was reborn. Such was the success of the undertaking that the land became a national park and the Salgados formed the Instituto Terra, dedicated to promoting the restoration and conservation of forestland.

Healing the land rekindled Salgado’s desire to photograph again. Following the trajectory of his career, we see the photographer, depleted physically and emotionally after his work on Migrations, taking succor from his environmental work. Regeneration of land and career proceeded in tandem, except that when he focused his camera anew, this time it was not on humanity, whose future seems uncertain, but rather on the planet, which he feels confident will endure. His new project is aptly named Genesis.

“Photography opened the world to me,” divulged Salgado. In doing so, it spared him the dreaded nine-to-five job, unlocked his creativity, and allowed him to inform society at large. But it also confronted him with a deeply troubling paradox, namely humanity’s nobility of spirit alongside its proclivity for unrivaled cruelty.

Nowhere were these traits more starkly revealed than during his work on Migrations. If we are to pull through as a species, he believes, then we need to keep our spirit of community alive and our family bonds intact, for these are attributes that have served us well since antiquity.

We would do well to heed his advice. With political discourse in the United States mired in bitter discord over how to deal with millions of illegal immigrants, and Europe inundated with those fleeing the charnel houses of the Middle East, Salgado’s photographs have never been more relevant. They remind us not only of how little has changed over the years with these cyclical crises, but also of what the consequences may be, should we fail in our responses to them.