DNAinfo reporter Ben Fractenberg addresses a rally—hosted by the Writers Guild of America—in New York City in November 2017. Days earlier, DNAinfo and Gothamist owner Joe Ricketts shut down the publications a week after employees voted to form a union

Two months later, Hamilton Nolan, a senior writer at Gawker, was talking with an organizer from the Writers Guild of America, East, a union largely of film and television writers, when the organizer told him that workers at one news website she hoped to unionize seemed scared of retaliation if they pushed for a union. Nolan surprised her by saying why not try to unionize his company, Gawker Media, which included Jezebel, Deadspin, Gizmodo, and Jalopnik. Soon Nolan was chatting up his coworkers, and within three weeks, nearly 40 Gawker workers met one afternoon at Writers Guild headquarters to discuss unionization.

The next day, Nolan posted a piece on Gawker with the headline “Why We’ve Decided to Organize.” While noting that Gawker was “a very good place to work,” Nolan wrote, “Every workplace could use a union. A union is the only real mechanism that exists to represent the interests of employees in a company.”

The recent burst of media unionization is one of the bright spots in a labor movement that has been declining for decades

“It was obvious that you needed to be unionized for the same reason that newspapers needed to be,” Nolan says. “There is always a structural imbalance in the workplace without a union. You can talk about getting better wages, better benefits, editorial protections, all those important things, but regardless of how good your job is, if you’re not working under a contract, you’ll always be at the mercy of your boss if you don’t have a union.”

Within days, an extraordinarily transparent debate had erupted in which Gawker employees posted their thoughts, pro and con, about unionizing. This online debate was fully accessible to the public. Also unusual, Gawker’s founder, Nick Denton—unlike many corporate executives in the U.S.—did not declare war against unionization. Denton instead said he was “intensely relaxed” about it. Tommy Craggs, Gawker Media’s executive editor, added that he was “politically, temperamentally and, almost, sentimentally supportive of the union drive.”

In promoting unionization back in 2015, Nolan said he wanted to ensure that everyone received a fair salary and that pay and raises were set in a fair, transparent, and unbiased way. In what became a recurring theme, he added, “We would like to have some basic mechanism for giving employees a voice in the decisions that affect all of us here.”

On June 3, 2015, Gawker’s employees voted 80 to 27 to unionize, becoming the first major website to take that step. (Truthout, a nonprofit progressive website, had unionized in 2009.) Gawker’s move sparked a movement, and within months, journalists at Salon, Vice Media, HuffPost, and the Guardian US had unionized. As this union wave grew, journalists at about 30 websites unionized and so did journalists at the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, The New Yorker, New York magazine, and The New Republic. And newsrooms are still continuing to unionize; the Hartford Courant, the Virginian-Pilot, the Allentown (Pa.), Morning Call,Refinery29, Fast Company, and WBUR in Boston have unionized in recent months, and workers at BuzzFeed and podcasting startup Gimlet Media have asked for union recognition. (Gawker Media filed for bankruptcy protection in June 2016 as a result of Hulk Hogan’s lawsuit, and two months later Univision acquired the company and picked up the union contract, even as it closed down the Gawker.com website.)

The legacy newspapers that have unionized recently have done so largely because of accumulated anger about downsizing, years without raises, and ever-worsening health benefits. Digital news sites generally unionized for different reasons: to lift the salary floor, win or improve basic benefits, and provide some cushion to the industry’s volatility. In digital, there was also a desire to bring some rules and rationality to what often seemed like capricious workplace decisions. In both legacy and digital, journalists also said they wanted a union so they could have more of a voice on the job.

“It feels like a real movement. There’s a lot of energy,” says Lowell Peterson, executive director of the Writers Guild of America, East. “It’s not as if we’re dragging people who are reluctant to talk to us. They’re eager to talk to us and sign up and get going.”

The recent burst of media unionization is one of the bright spots in a labor movement that has been declining for decades. Organized labor first achieved major strength in the United States during the New Deal, with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935, which gave private-sector workers a federally protected right to unionize. In 1930, about 11 percent of non-agricultural workers were union members; that climbed to almost 35 percent in 1954, before sliding to just 10.5 percent in 2018. The decline in recent decades has been fueled by many factors, including the loss of manufacturing jobs, corporate America’s growing resistance to unions, and labor’s image problems, including union corruption and unions often being viewed as obsolete and obstructionist. But with many Americans upset about stagnant wages and increased income inequality, unions have their highest approval rating in 15 years, with the strongest approval coming from Americans aged 18 to 34.

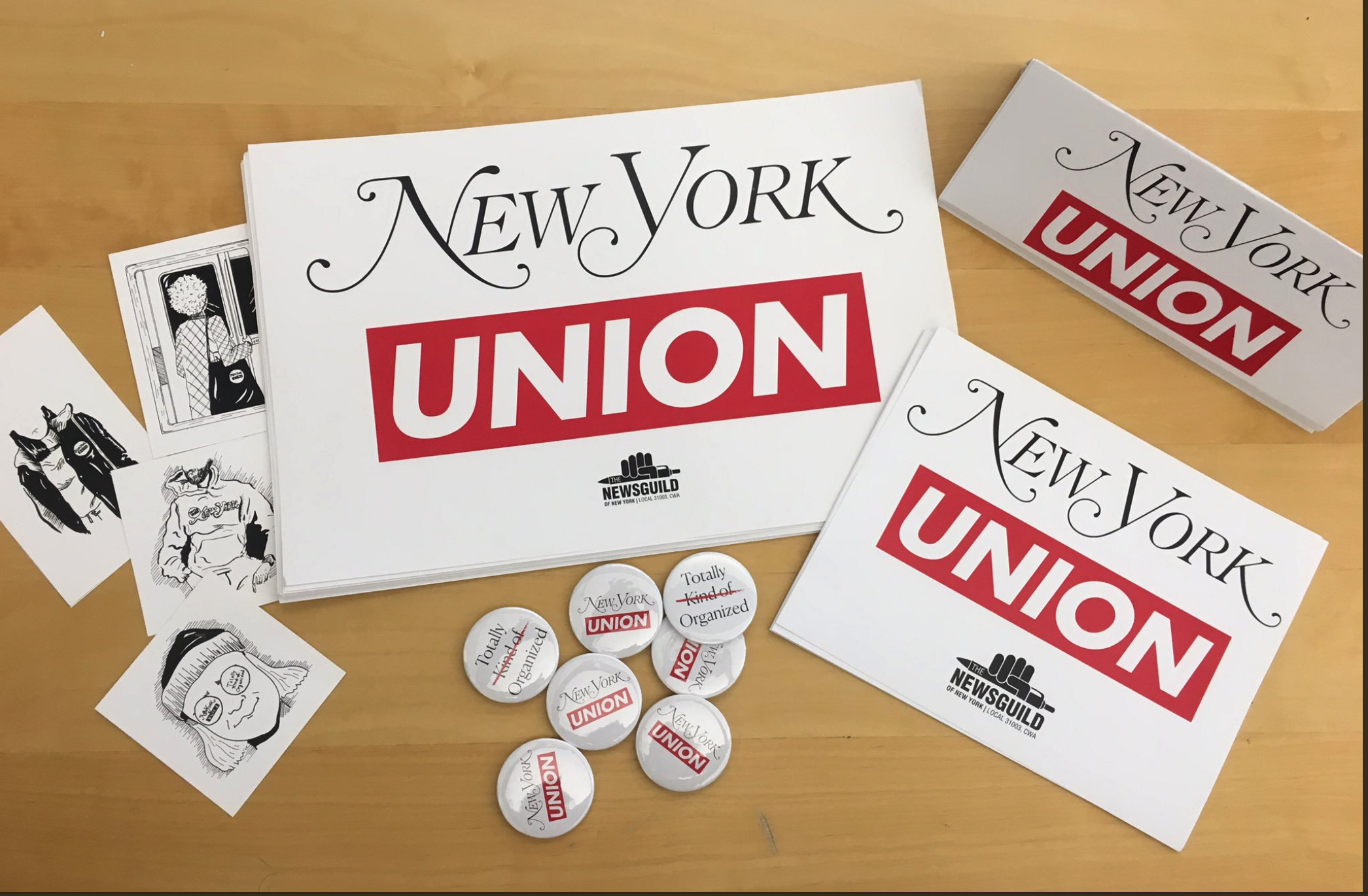

New York magazine, which unionized in early 2019, is among the recent wave of publications—both legacy and digital—that have done so

Unionization of journalists caught fire soon after the Newspaper Guild was founded in 1933. Many reporters and copy editors had grown fed up with low pay, layoffs, and earning far less than typesetters and pressmen. One challenge the Newspaper Guild’s organizers faced was convincing journalists that unions weren’t just for the blue-collar proletariat. In city after city, the Newspaper Guild won raises, overtime pay, and a guarantee that layoffs could only be for just cause, and it ultimately won health coverage and pensions for most Guild members. At some papers, the journalists also won a guarantee that powerful publishers—they often tilted well to the right—could not tilt the newsroom’s journalism. To be sure, unions at some newspapers were weak and not terribly effective at winning raises or better conditions.

Today’s wave of media unionization comes as the industry is in crisis. Many legacy newspapers, especially local ones, face a severe financial squeeze. The digital media are in the middle of a shakeout, with too many websites chasing too few advertising dollars, as Facebook and Google gobble up much of that revenue. There have been layoffs galore—for instance, Vice Media laid off 250 in February and BuzzFeed laid off 200 in January. Just weeks later, BuzzFeed’s staff announced a major effort to unionize with the NewsGuild.

Some longtime critics of labor say unionization has hurt media companies’ profitability and fueled some of the layoffs. But labor’s supporters say the layoffs and shakeout had already begun before the wave of unionization. “In an extreme situation, a hardball union play could potentially hasten the shutdown of a publication,” says Alan Mutter, a former newspaper editor who recently retired from teaching media economics at the University of California, Berkeley. “But my guess is there are very few union leaders who would push so hard that they accelerate those forces of demise. The problem is that neither union nor management, even when operating hand in hand and heart to heart, can prevent any of those forces that are bearing down, especially on local newspapers.”

“This generation is tired of hearing that this industry requires martyrdom, that it requires that you suck it up, that you accept low wages and long hours.” —Nastaran Mohit, NewsGuild NY local

David Chavern, president of the News Media Alliance representing 2,000 newspapers in the U.S., says, “We are neither for or against unionization.” He adds, “We are focused on the challenges posed to journalism by the major platforms (Facebook and Google, in particular), and I don’t think that having or not having a union changes those market dynamics.”

But union organizers say unionization actually improves publications and thus helps increase readership. They argue that unions, by bringing better pay, benefits, and working conditions, attract better journalists and reduce staff turnover, by helping persuade journalists to stay. “In the past five years, we’ve seen a lot of businesses starting on the backs of people who haven’t been properly compensated and doing tricks to make people work longer and harder,” says Emily Bell, head of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University. “If costs go up because creating a union means you have to figure in health coverage, working hours, proper compensation for leave, that has to be a positive thing, even if it means we have fewer digital businesses.”

“This generation is tired of hearing that this industry requires martyrdom, that it requires that you suck it up, that you accept low wages and long hours,” adds Nastaran Mohit, chief organizer for the NewsGuild’s New York local. “The demands of this work have increased significantly. The industry has been asking workers to do more and more with less.”

Vice Media was one of the first companies to unionize after Gawker. “The biggest motivating factor was money,” says Kim Kelly, a longtime music editor at Vice who was one of the 250 Vice employees laid off in February. “We were being paid very, very low, very much under the market rate. People were having a very hard time living in New York, and they expected us to deliver this inspiring, challenging content at the same time that people couldn’t afford rent, couldn’t afford lunch, were living with their parents—all while Vice’s founder was buying a $23 million mansion.”Several of the early digital contracts made impressive gains. Some Vice writers were earning just $35,000, and the contract set a $45,000 floor, giving some writers an immediate $10,000, or 28 percent, raise. Gawker’s first contract called for a 9 percent raise over three years, as well as a minimum salary of $50,000 for any full-time employee and a minimum of $70,000 for senior writers and editors. To help reduce the helter-skelter aspect of raises, every Gawker employee was given the right to meet at least once yearly with his or her supervisor to discuss merit raises. In case of layoffs, Gawker pledged two weeks’ severance pay for every year on the job, and it improved its 401(k) plan to give a dollar-for-dollar match for the first 3 percent of pay.

Impressed by such gains, more digital journalists unionized, including those at Thrillist, Mic, Salon, Jacobin, ThinkProgress, and Al Jazeera America (before it closed). “Once Gawker did it, other folks said, ‘We could do this,’ and it quickly became the norm in the new media world,” says Dave Jamieson, HuffPost’s labor reporter.

Battered by cutbacks and layoffs in traditional newsrooms, the NewsGuild at first held back from seeking to unionize digital newsrooms

HuffPost’s first union contract, reached in January 2017, had some innovative language to enhance newsroom diversity and ensure editorial independence amid concerns that publisher Arianna Huffington’s business interests—her being on the board of Uber, for instance—could skew coverage.

Battered by cutbacks and layoffs in traditional newsrooms, the NewsGuild, formerly the Newspaper Guild, at first held back from seeking to unionize digital newsrooms. The main reason: the NewsGuild, which represents 25,000 journalists at 200 media organizations, was in a defensive crouch, preoccupied with the industry’s crisis and newspaper shutdowns and layoffs. But seeing the Writers Guild unionize numerous news sites, the NewsGuild jumped in and unionized The Guardian US, Law360, and In These Times.

The NewsGuild had at first viewed digital and legacy differently. Many newspapers were big, lumbering, decades-old companies, while digital sites were often new, small, and funded by Silicon Valley, with many workers doing coding and video, far different from the work done by traditional newpaper journalists. Nowadays, however, as newspapers and magazines have vastly expanded their digital work, Grant Glickson, president of the NewsGuild’s New York City local, says, “We don’t view digital and legacy print as different—we view it all as one and the same.”

For decades, the Los Angeles Times had a reputation as the nation’s most anti-union newspaper. That was perhaps understandable, considering that a union activist dynamited the Times building in 1910, killing about 20 of the newspaper’s employees. General Harrison Gray Otis, who acquired partial ownership of the Times in the late 1800s, was a vehement foe of unions, and so was his son-in-law Harry Chandler. Those views persisted at the Times throughout much of the twentieth century, with the paper serving as a megaphone for the LA business community’s campaign to keep the city as “open shop,” as non-union, as possible.Not surprisingly, Times employees were wary of pushing for a union. Nor was there any urgency to do so during the last quarter of the twentieth century because the Chandlers had transformed the Times into one of the nation’s finest newspapers and paid its journalists handsomely. But all that began to change after the Chandler family sold the paper to the Tribune Company in 2000. That company—which real estate magnate Sam Zell bought in 2007, before dragging it into bankruptcy—didn’t have the Chandler’s expansive public-minded view about investing in journalistic excellence. Instead, the Tribune Company, caught up in the legacy media’s financial crisis in the digital era, shuttered many of the Times’s domestic and foreign bureaus, downsized its newsroom from 1,200 to around 400, and didn’t give across-the-board raises many years.

“It felt like death by 1,000 cuts,” says Carolina A. Miranda, a culture reporter for the Times. Bettina Boxall, who won a Pulitzer Prize for her environmental coverage, says, “I’ve been here for 30 years, and the past 20 years have been endless corporate tumult and mismanagement. It has taken the form of not just endless layoffs and buyouts, but also years without raises and having to pay more for health benefits and more for parking.”

Discontent grew in October 2017 when an ownership team that succeeded Zell (and renamed the company Tronc for Tribune Online Content) fired the Times’s top editors and named as editor-in-chief Lewis D’Vorkin, whom the newsroom believed wouldn’t champion robust journalistic values. Then Tronc eliminated the weeks of accrued vacation pay that employees had accumulated over the years. “That sort of sparked it,” says Anthony Pesce, a data reporter.

Pesce and a half-dozen co-workers formed the nucleus of a pro-union effort. “There was just an overwhelming sense that management was bad, that there wasn’t anything we could do about it,” Pesce says. “We didn’t have a seat at the table. That was when people really realized that if they stand up and say something about this, we can actually effect some change.”

Members of the Los Angeles Times Guild. Times journalists voted overwhelmingly to unionize in January 2018

Pesce contacted the NewsGuild, and it dispatched Nastaran Mohit, who was based in New York. Pesce admits that he and his coworkers knew little about organizing. They were in a rush—to announce their effort on social media and hold a unionization vote. But the NewsGuild urged them to slow down. “They said, ‘You’ve got to talk to everyone,’” Pesce says. “‘You have to make sure everyone’s views are heard. You have to hold everyone’s hands a bit.’”

To rally workers behind the union drive, Pesce, Paul Pringle, a prize-winning investigative reporter, and other Times staffers did something highly unusual—they did some hard-hitting investigative reporting about their own company, specifically about the excessive spending of Tronc’s executives. The Los Angeles Times Guild posted those stories on Twitter, Facebook, and its own website, and shared them with other publications.

The union supporters wrote that even as Tronc was chopping newsroom positions, Michael Ferro, Tronc’s chairman and largest shareholder, used a private jet that cost the company $8,500 an hour to operate and a total of $4.6 million in less than two years. Tronc’s CEO, Justin Dearborn, had received $8.1 million in compensation in 2016. In December 2017, two weeks before the scheduled unionization vote, the LA Times Guild’s investigating team reported that Tronc had awarded a $5 million-per-year “consulting agreement” to Ferro for three years.

“It was just rapacious,” Miranda says. Matt Pearce, a national desk reporter, adds, “Tronc’s model was they’ll continue pumping equity out of the paper, and they’ll figure out what comes next, and we in the newsroom will continue to make sacrifices and do dangerous work, all without annual raises to keep up with the cost of living in southern California. It was untenable. We saw that things were getting worse. So we carved out our own path.”

The company hired anti-union consultants to fight back. Management distributed a flyer to the staff, saying, “Don’t be misled by the Guild’s promises.” Tronc warned that things could get worse with a union, telling the newsroom, “There is no obligation on the part of a company to continue existing benefits and it is not against the law for the company to offer reduced wages and benefits in bargaining.”

Notwithstanding management’s opposition, in January 2018, the Times journalists voted overwhelmingly, 248 to 44, to unionize for the first time in the paper’s 137-year-history.

Throughout the unionization drive, there was a largely unspoken goal—to pressure Tronc to sell the newspaper to a public-minded owner who cared about journalism and would invest in the newspaper, instead of siphoning away its resources. A month after the unionization victory, Tronc agreed to sell the Times and The San Diego Union-Tribune for $500 million to Patrick Soon-Shiong, a billionaire doctor.

For decades, the Los Angeles Times had a reputation as the nation’s most anti-union newspaper

With its new owner, the LA Times is hiring dozens more reporters and editors and re-opening bureaus. The paper has revamped a diversity training program that staffers complained was being misused to hire top-notch reporters of color for low pay. Before unionization, complaints about the diversity program were largely ignored, but with unionization, the program was fixed.

Even so, contract talks between union and management still get bogged down, most recently over discussions regarding intellectual property. Early this year, the union argued the company was being “draconian” about restrictions on journalists’ selling rights to books and other creative projects. Norman Pearlstine, the LA Times’s executive editor, insisted that the company’s stance on intellectual property was reasonable. Pearlstine notes that the company has increased payroll by more than 10 percent as “a significant investment in retention and recruitment,” while also improving paternity benefits and transit benefits. “We have also committed to giving employees a voice in many matters, such as diversity and inclusion,” he says.

The LA Times journalists helped precipitate a sale to a deep-pocketed, public-spirited owner, and journalists in several other cities hope that unionization will help them achieve a similar result. Unions are among “the few people making the point about the failure of the local press to represent the public interest,” says Ken Doctor, a newspaper industry analyst who writes the Newsonomics column for Nieman Journalism Lab. “Union efforts have put back into the public conversation what is the responsibility of those who own the press and work in the press to their communities.”

Even though most news websites have liberal reputations, their executives are sometimes unenthusiastic or outright opposed to unionization, an attitude that sometimes angers liberal readers. In one of digital management’s first major statements about unions, Jonah Peretti, Buzzfeed’s founder and CEO, said in August 2015 that unions might be appropriate in a factory setting, but not in a field like digital journalism, which he said requires dynamism and flexibility. “A lot of the best new-economy companies are environments where there’s an alliance between managers and employees. People have shared goals,” Peretti said, adding that often when there’s a union, “the relationship is much more adversarial.” Saying that unions often insist on rules defining individual roles, he said, “for a flexible, dynamic company” that “isn’t something I think would be great.”In February of this year, three weeks after BuzzFeed laid off 15 percent of its workforce, its editorial staff announced that 90 percent of eligible workers had signed cards saying they wanted to join the NewsGuild. Ben Smith, editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News, said the company looked forward to “meeting with the organizers to discuss a way toward voluntarily recognizing their union.” Neither Peretti nor Smith would comment for this story.

“Union efforts have put back into the public conversation what is the responsibility of those who own the press and work in the press to their communities.” —Ken Doctor, Newsonomics

Like Peretti, Jacob Weisberg, at the time the Slate Group’s chairman and editor-in-chief, also voiced opposition to unionization. In an email to staffers in March 2017, he wrote that unionization would disrupt the “flexibility and fluidity” of Slate’s newsroom and could threaten efforts to be “a sustainable, profitable business.” Weisberg added that a future with a union is “filled with bureaucracy and procedure. That world is just not Slate-y … A union fosters a culture of opposition, which is antithetical to our way of doing things.”

Nonetheless, Slate’s staffers voted overwhelmingly in January 2018 to join the Writers Guild. Over the ensuing 11 months, however, Slate’s workers grew frustrated about failing to reach a contract with management. So in December, Slate’s staff voted 52 to 1 to authorize a strike. The main sticking point: Slate’s management, despite the website’s progressive reputation, was insisting that workers be allowed to opt out of paying any fees to their union—similar to right-to-work laws abhorred by unions and liberals. In January, Slate dropped that demand. “We were super relieved and surprised,” says Slate audience engagement editor Aria Velasquez. With that demand dropped, the two sides quickly negotiated a contract that includes a $51,000 minimum salary and across-the-board raises with higher percentages for those with lower salaries. The deal also codifies anti-harassment policies, creates a diversity task force, and gives Slate’s journalists rights to derivative works. Slate executives declined to comment.

Probably the most-discussed unionization episode in digital media involved DNAinfo and Gothamist, two local news websites owned by Joe Ricketts, the billionaire founder of TD Ameritrade and patriarch of the family that owns the Chicago Cubs. DNAinfo bought Gothamist in March 2017, and the next month, the vast majority of the sites’ combined staff in New York signed cards saying they wanted to unionize, fearing the merger could result in layoffs. Ben Fractenberg, the longest-serving reporter for DNAinfo, says there were also concerns about fair pay, editorial standards, and the “very scattershot” way raises were given.

Ricketts declined to recognize the union based on the signed cards, insisting instead on a formal unionization vote conducted by the National Labor Relations Board. Ricketts made his opposition clear, writing to the staff, “As long as it’s my money that’s paying for everything, I intend to be the one making the decisions about the direction of the business.” Dan Swartz, chief operating officer of DNAinfo, sent the staff a letter, noting that Ricketts had invested “literally tens of millions of dollars of his own money” in the site and asking, “Would a union be the final straw that caused the business to be closed?” In September 2017, the month before the unionization vote, Ricketts wrote a blog item called, “Why I’m Against Unions At Businesses I Create”: “I believe unions promote a corrosive us-against-them dynamic that destroys the esprit de corps businesses need to succeed … It’s my observation that unions exert efforts that tend to destroy the Free Enterprise system.”

Even though most news websites have liberal reputations, their executives are sometimes unenthusiastic or outright opposed to unionization

Nonetheless, 25 of the 27 workers at the news sites’ New York office voted in October 2017 in favor of unionizing with the Writers Guild. A week later, Ricketts shut down the sites, not just in New York, but in Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington, costing 115 workers their jobs. That day Ricketts, who founded DNAinfo in 2009, posted a letter online that said in part: “DNAinfo is, at the end of the day, a business, and businesses need to be economically successful if they are to endure. And while we made important progress toward building DNAinfo into a successful business, in the end, that progress hasn’t been sufficient to support the tremendous effort and expense needed to produce the type of journalism on which the company was founded.”

Journalists at DNAInfo and Gothamist were shocked to discover their websites suddenly shut down and redirecting readers to Ricketts’ letter. “I was definitely stunned,” says Fractenberg, who was covering a Manhattan Supreme Court hearing when he learned of Ricketts’ decision. “I couldn’t believe it happened.… It was seen that they were laying us off only because of the union.” In a statement at the time, a spokeswoman for DNAInfo said: “The decision by the editorial team to unionize is simply another competitive obstacle making it harder for the business to be financially successful.”

When journalists took jobs at Law360, a news service that covers legal matters, they were sometimes surprised to discover a noncompete clause in the boilerplate of their employment contract. Those who voiced concern were often told, ‘Don’t worry—it’s just a formality; it’s never been enforced.’But when Stephanie Russell-Kraft left to take a reporting job at Reuters in the fall of 2015, an attorney for Law360 sent her a letter, telling her she was violating her noncompete. Law360’s lawyer also wrote to Reuters’ general counsel about Russell-Kraft’s noncompete, and two days later Reuters fired her.

“That was really the galvanizing moment for people at Law360 to unionize,” says Juan Carlos Rodriguez, a senior writer who covers environmental law. “The noncompete was outrageous. It completely violated industry norms. We started to see what it was—a wage depressant. By preventing us from going to competitors who paid better, they didn’t have to pay us more.”

Several other management policies were also riling Law360’s employees. According to Rodriguez, Law360 had a policy that didn’t pay time-and-a-half when employees worked more than 40 hours a week, but instead paid just half of their regular hourly pay, sometimes less, for their overtime hours. It also had a quota system—about the number of stories written, stories edited, and news pitches—that many found onerous. Another concern was salary; Law360, based in Manhattan, paid some employees just $40,000.

Tony Barone, second vice president of the NewsGuild of New York, demonstrates outside The New York Times building, in New York, in June 2017

After the noncompete contretemps involving Russell-Kraft, several workers formed a union organizing committee, and within months a majority of workers had signed pro-union cards. Law360, a subsidiary of LexisNexis, rejected the workers’ request for voluntary union recognition, and a unionization vote was scheduled. To persuade workers to vote no, Law360 hired the Labor Relations Institute, an anti-union consulting firm. Law360 had its employees attend four anti-union sessions, where they were warned that things might not improve with a union and that workers might be unhappy with what’s in their contracts. Rodriguez, who was one of the leaders of the unionization effort, said one consultant told the workers, “Not voting in the union is free. Voting the union in, you pay dues.”

Notwithstanding Law360’s anti-union push, its workers voted 109 to 9 to unionize with the NewsGuild in August 2016.

In early 2018, after a year of negotiations without reaching agreement, Law360’s workers were frustrated. Danielle Smith, a general assignment reporter, says, “We thought management was playing hardball to drag out the negotiations. We saw that the only way to get significant movement at the bargaining table was to show our solidarity.”

One day the workers walked out of their offices, on West 19th Street in Manhattan, for 30 minutes. Next came an hour-long walkout. In late October the staff voted 141 to 11 to authorize a strike. Then in November came an even longer walkout, with the NewsGuild placing a 15-foot-tall inflatable rat outside Law360’s offices.

When a top executive of the company visited, the workers wore union T-shirts. One Friday in December, everyone walked out and picketed the front and back doors. Two days, later, the two sides finally reached a deal. The Law360 workers celebrated and approved the contract, 168 to 0. “Over the course of several years the bargaining committee could talk until it was blue in the face,” Smith says. “But it wasn’t until the company saw the union was solidly behind the bargaining committee, that they would make some real movement.” Law360 and LexisNexis officials declined comment.

The contract provides an immediate 22 percent raise on average and sets a $50,000 minimum. It provides for an annual bonus pool of at least 3 percent of payroll, and for the first time, the workers are guaranteed paid sick days and bereavement time. As for the noncompete provisions, Law360 had agreed to remove them earlier when New York State’s attorney general threatened to sue over the issue.

The Law360 contract has an unusual successorship provision, meaning that if LexisNexis sells Law360, any acquirer would be required to comply with the contract’s provisions—and could not, for instance, order a pay cut. Law360’s union said in a statement, “Let this incredible contract be a testament to what media workers can accomplish when they unionize and win a seat at the table.”

Law360’s successorship clause was one of several innovative provisions that digital journalists have demanded—and won

Law360’s successorship clause was one of several innovative provisions that digital journalists have demanded—and won. Workers at the Gizmodo Media Group, formerly Gawker Media, have also won a successorship clause.The Nation’s contract gives four months of fully paid parental leave to employees with one year or more of service. In their first union contract, journalists at The Intercept won unusual language on parental leave, calling for four months of maternal leave and four months of paternal leave. The Intercept contract also has an innovative provision on diversity, saying, “the Employer will ensure that it interviews at least two candidates from groups traditionally underrepresented in journalism (i.e. women, people of color, or those identifying as LGBTQ+) prior to making a hiring decision.”

The Onion’s union contract includes anti-harassment language and calls for hiring a consultant to “conduct a climate assessment” of how workers are treated. The new Vice contract negotiated by the Writers Guild contains non-discriminatory language about not just race and gender identity, but also socioeconomic status and criminal convictions. Some of these provisions in digital media contracts go far beyond what was included in traditional newspaper contracts.

Charles J. Johnson, a homepage editor at the Chicago Tribune, couldn’t help but notice the explosion of unionization in digital media, and he began thinking, “Why not us, too?” The Tribune’s newsroom had been repeatedly downsized, and its once-good salaries had fallen well below those at the unionized Chicago Sun-Times.The Tribune, which has won 27 Pulitzer prizes, has long been Chicago’s establishment paper, with a conservative editorial page and a staunch anti-union history. The Sun-Times has been a feisty tabloid for blue-collar Chicago and has long been one of the nation’s best tabloids. But even as the industry crisis forced the Sun-Times to cut back its staff and journalistic ambitions, its union contract helped maintain its pay scale, pushing it above the Tribune’s. (In 2013, the Sun-Times was purchased by a group of private investors that included the Chicago Federation of Labor.) Under the Guild contract, Sun-Times journalists earn at least $66,000 after five years, while one prominent Tribune reporter complained of earning $54,000 after eight years.

In October 2017, Johnson heard that journalists at the LA Times were unionizing with the NewsGuild. (At the time, Tronc owned both the Tribune and LA Times.) “That re-energized me,” says Johnson, who, daunted by the challenge, abandoned an earlier attempt to organize the paper’s newsroom.

Johnson reached out to the NewsGuild and to two fellow reporters: Megan Crepeau, who covers Chicago’s criminal courts, and Peter Nickeas, who covers violence. The three brainstormed, chatted up others, and soon there was a 40-person organizing committee. Two nationally known columnists, Clarence Page and Mary Schmich, joined the effort.

The Trib’s staff was overflowing with grievances. “This famously anti-union place, there wasn’t a union here for a long time in large part because people felt they didn’t need it,” Johnson explains. For decades, the Tribune had paid its staff more than the Sun-Times did to help keep a union out, but things had changed as owners Sam Zell and then Tronc were tight-fisted about raises and benefits. “Some people work second and third jobs to afford to work at the Tribune,” Johnson says. “There are reporters here with super-significant beats making less than 50 grand a year. These are professional-class jobs paying working-class wages, and these people have working-class worries about being downsized, laid off, cast aside in a market that is really stripped down.”

As in Los Angeles, the Tribune’s journalists weren’t fighting just for better pay, but for better journalism. “The newsroom was bleeding. It continues to bleed,” Crepeau says, noting that the newsroom has 184 employees, down from 223 last spring. “Salaries can’t keep up. We can’t retain talent. The Guild folks provided us with pay scales for papers all around the country. That made me want to cry.”

As in Los Angeles, the Tribune’s journalists weren’t fighting just for better pay, but for better journalism

In April 2018, the Tribune organizing committee went public and within weeks, 85 percent of the staff had signed pro-union cards. Tronc initially rejected the union’s call to grant voluntary recognition, but under pressure, it recognized the union in May. Bruce Dold, the Tribune’s editor-in-chief and publisher, said, “As we move ahead, we need to be united as one organization with an important purpose—to help the company transform and thrive as a business, and to serve our readers world-class journalism.” (In October 2018, Tronc changed its name back to Tribune Publishing. The company did not respond to requests for comment.)

“The short of it is people don’t like the instability in the newsroom, and they wanted some way to advocate for themselves,” says Nickeas. “The Tribune hasn’t had an ownership that’s interested in journalism in years. A union is a way to say, these are our priorities. We don’t want to be dictated to by Sam Zell or whoever spins us into bankruptcy or whoever is our fourth or fifth owner in so many years.”

Tribune Publishing and the union have not yet begun contract negotiations, but the company has already shelved a threatened move to adopt a health insurance plan staffers say is worse than the current one.

“I don’t think anyone said this was the perfect solution to what ails the Tribune or the media writ large,” Johnson says. “But this is the tool available to us, and we’re finally starting to use it.”