A woman attends a rally against gender violence in Santiago, Chile in 2018

Translated by Dick Cluster. Leer en español.

There are no crimes in Chile more violent than the ones committed against women.

In the country with the fewest homicides in Latin America, and one of the safest, a woman is found unconscious, her eyes ripped out. The body of a young woman, seven months pregnant, is found a year after her disappearance just a hundred yards from her house, under a layer of lime and concrete. A woman is murdered, at home, alongside her mother. Another is recovering in a hospital after a knife attack that killed almost all of her family; her mother and younger sister died, her father managed to escape with a chest wound, crying for help.

These are not crimes linked to drug traffickers, gangs, or political repression. These are examples of women attacked in Chile by men with whom, in most of the cases, they were in intimate relationships—current or former husbands or domestic partners, a crime that in Chile is called femicide. They are recent cases of extreme violence against women in a country which, even by official figures, has seen 24 such femicides in the first half of this year, and 53 attempted ones.

And yet, femicides and other attacks against women—in spite of their frequency, in spite of specific legal prohibitions, in spite of longstanding efforts by public and grassroots organizations to make violence against women more visible as a widespread public and social problem—are still portrayed in large swaths of the Chilean media as exceptional and isolated events.

Whether in the form of a news brief in a mainstream newspaper or of serialized reports in the tabloids and on morning TV shows, violent crime against women tends to appear in the media as an individual or family drama.

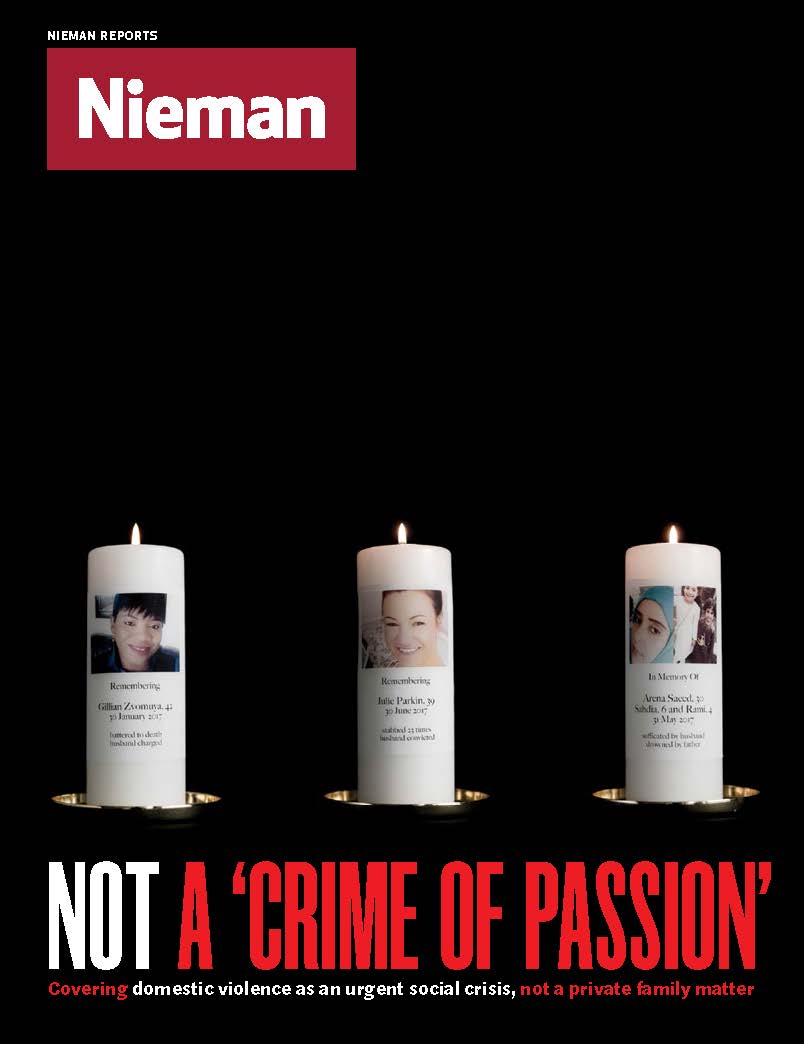

This stubborn narrative of violence against women as a personal issue (that is, as private and even shameful to the women) traditionally figured in the Chilean press under the rubric of “crimes of passion.” Mistreatment of women was presented as a result of a kind of fit or outburst, terminology that can also be used in court cases as an extenuating circumstance. The perpetrator “killed for love” or “was blinded by jealousy,” which meant that the woman attacked or killed was, in some fashion, complicit with her attacker. Her clothes, her physical characteristics, her habits, her hidden motives were all things the attacker could not resist.

Today, in many national media, this narrative has taken a new form: a crime melodrama or detective story. Its leading platform is the television screen, especially on the morning shows, with their blend of information and entertainment.

This stubborn narrative of violence against women as a personal issue traditionally figured in the Chilean press under the rubric of “crimes of passion”

In these serialized stories—which follow unsolved or high-impact cases—the attacker appears as a mere instrument, the medium through which inscrutable and capricious fate has found a victim. The murderer’s intelligence challenges police and prosecutors or exposes their incompetence. The disappeared or murdered woman is scrutinized—not to humanize her, not to tell who she is, but rather to find in her life the keys that will unlock the mystery of her death. Her Facebook page, her habits, her makeup, or her clothes are no longer explicitly suggested as provoking the attack. Instead they become clues, but their function within the story of aggression is strangely similar, and the effect—to sow suspicion about the victim or put her on the spot—is the same.

The medium of television adds new doses of spectacle to the formula: dramatic re-creations with evocative soundtracks, accompanied by the opinions of retired detectives or even so-called clairvoyants. In recent years, the institution that receives complaints about television programming, the National Television Council, has logged a record number of such comments about the coverage of two cases of violence against women. In one, the psychological profile of a murdered young woman was divulged by a TV station. In the other, gynecological information about a woman was revealed in the middle of the trial of her aggressor.

It’s as if we were reading “The Handmaid’s Tale” in the key of “Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

“Above all, the morning shows appeal to a sense of spectacle,” says Claudia Pascual, who was Chile’s first minister for women and gender equity, a cabinet-level position created by President Michelle Bachelet. “They drag out an old case with novel episodes. They spin theories, speculate, create a spectacle without at all aiding the investigation. And there’s no reflection or analysis, no condemnation of the crime as a case of gender-based violence. They turn it into a show, a Netflix series.”

The persistence of these narratives in their various forms contrasts with the long history of the Chilean feminist movement, whose leaders raised their voices almost a century ago, and with the tenacious work that hundreds of women began under the Pinochet military regime to make violence against women a public policy issue.

It is, on the other hand, consistent with persistent gender inequality that is demonstrated by the small number of women in any positions of power in the country, whether it be in government, business, or religious organizations.

It wasn’t until 1994 that Chile approved a family violence law. In 2005, it made “habitual mistreatment” a crime. In 2010, it passed a femicide law that applied to murders committed by current or former spouses or live-in partners. The introduction of the term “femicide” and the public record-keeping of such crimes propelled discussion and attention to domestic violence. It gave the mass media an accurate term to describe the murders of women by their partners. It showed the pattern of violence that had, in many cases, gone on for years. Often, the response of the police and the justice system had been insufficient.

In 2018, Chilean women, drawing on the international #MeToo movement and the Argentinian anti-femicide movement #niunamenos (“not one [woman] less”), gathered force, paralyzing universities and bringing thousands of women into the streets.

One of the main effects of this “third wave” Chilean feminism on the press has been to open more spaces for voices demanding gender equality and calling out machismo. Grassroots groups that had been doing community work for years began to be heard in the media, which started giving more space to conversations about sexism, street harassment, and gender stereotypes. In many cases, the press began to react to pressure from social networks in which activists and others called on the journalists to give non-sexist coverage to these cases.

Thanks to all of this persistent political, institutional, and social effort, it has grown more and more difficult for the media to continue romanticizing femicides as crimes of passion, to present these crimes as an abnormality affecting the life of just one woman, whose misfortune the audience can watch with horror or commiseration, but above all, as a curiosity.

Yet, in spite of all the legislative advances and vigilant work by activists, civil society, readers, viewers, and NGOs, the media repeatedly fail to present these stories as the most extreme expression of an inequality that permeates all realms of the nation’s life.

Journalism must not justify crimes against women by way of romanticizing the perpetrators, nor by playing the puzzled detective. The challenge to the press is to see and present violence against women as a problem that affects not only those who are attacked or killed, or their families and friends, but every single member of society.