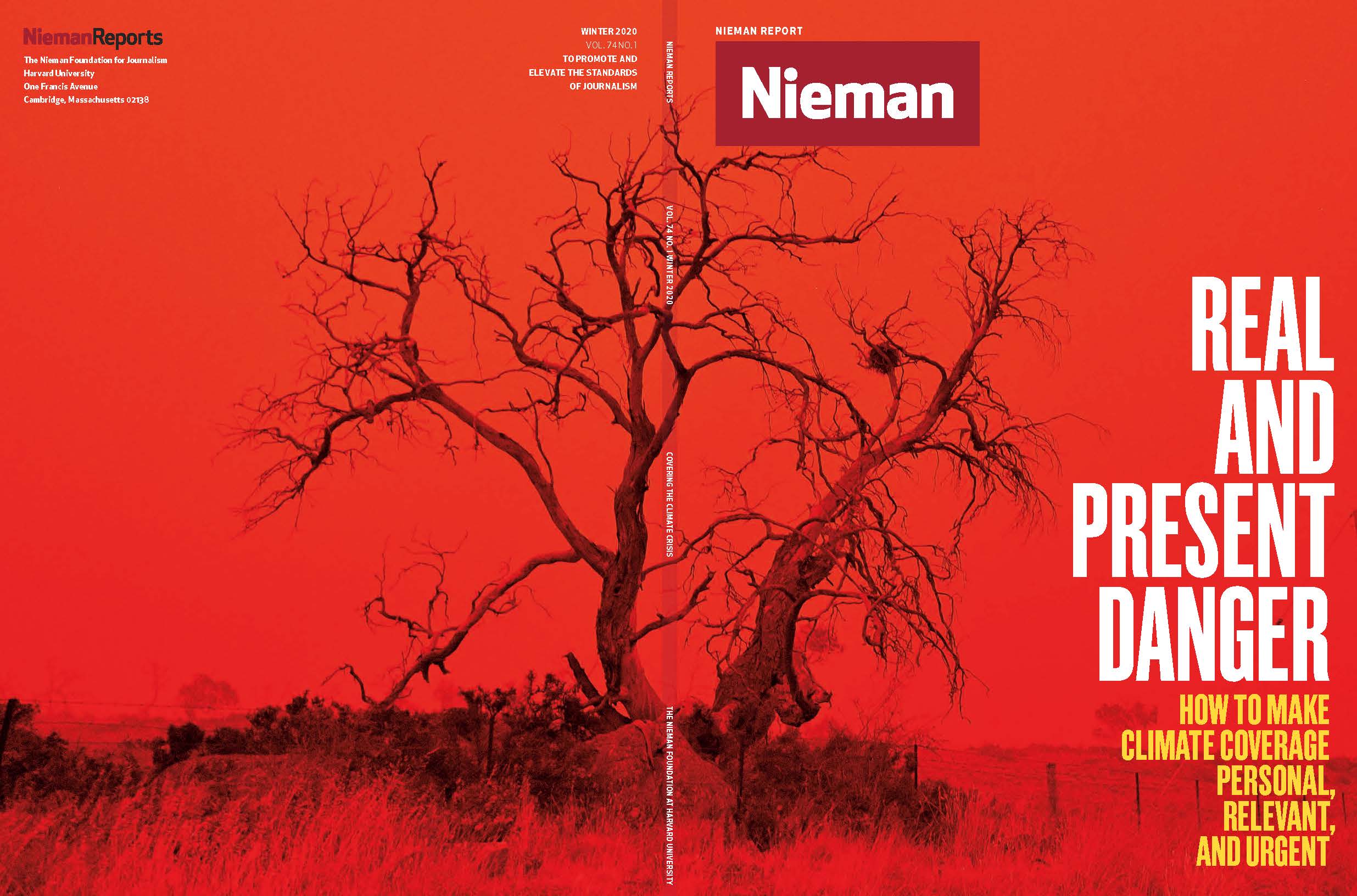

Nils Arvid Guttorm—one of the subjects of “The Hunt for Climate Changes,” a feature by Norwegian public broadcaster NRK about how climate change is impacting local people throughout the country—with his reindeer in Finnmark, above the Arctic Circle. In recent years he’s struggled to keep them fed in the winter as temperatures rise above freezing, which can cause a hard layer of ice to form on the ground and make it impossible for the reindeer to reach their food

These are heady times for anyone scrutinizing climate change coverage. Take the volume of coverage, for example, which seems to be on a sharp upward trend this year. More than 300 media outlets were reported to have joined the recent global initiative, Covering Climate Now, to increase coverage in the run-up to the United Nations Climate Action Summit that took place in September.

Prompted by The Nation and Columbia Journalism Review, the initiative suggested that major news organizations should break the “climate silence” to cover the “defining story of our time.” But “more” does not mean “better,” if it leads to more inaccurate reporting of climate science on Fox News or in the Daily Mail.

One prominent academic warned that the Covering Climate Now initiative could become an “echo chamber for climate change activism.” The pros and cons of advocacy journalism have also been examined, including The Guardian’s Keep it in the Ground Campaign.

The Guardian is one of several outlets who have changed their house style to use “climate emergency” over “climate change” and “denier” over “sceptic.”

So there is plenty of debate about volume, language, and advocacy. But largely missing is more examination of the quality of climate journalism, and what it might look like. “Quality” is a slippery concept for media scholars, but some have tried to unpack it as it relates to climate journalism.

There is consensus that climate journalism should be accurate, well-sourced, and reflect complexity and uncertainty as appropriate (so no space, for example, for deniers of the basic climate science, but yes to diversity of views where the science is uncertain or on policy options). Some good practices are summarized here.

But what about the huge range of audiences around the world? And the plethora of different platforms, types of reporting (issue-driven or event-driven), and varieties of media organization?

“Quality” will mean different things to different journalists and different audiences, but to start the discussion, we suggest these five criteria beyond the normal editorial standards: 1) relevance to audiences; 2) out of the environment box; 3) potential solutions; 4) multimodal reporting; and 5) from global to local.

1. Relevance to the everyday lives, experiences, and passions of audiences

Climate change has often been perceived to be remote in time and place, complex, and depressing—all of which scholars see as an obstacle to public engagement. But this is changing.

Advances in climate modeling have allowed scientists to link some extreme weather events—such as droughts, heat waves, and floods—to climate change. Reporting that the severe 2019 European heat wave was made more likely due to climate change, or that Hurricane Dorian was made more severe, has become commonplace.

This may be changing public opinion on climate change. Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Communication, has argued that the increase in extreme event attribution may be partly responsible for growing concern about global warming in the U.S.

But event attribution reporting is more difficult than it might seem. Climate change cannot be said to deterministically cause any extreme weather; instead, it creates the conditions in which extreme weather is more severe, or more likely to occur.

The best reporting steers clear of overly simplified statements (such as “climate change caused the European heat wave”) in favor of more nuanced scientific explanations, clarifies the variables examined in relevant studies, and connects the extreme weather to human lives and experiences, such as water restrictions or heat warnings.

For example, The New York Times reported in 2015 that the warming trend had made the California drought more severe, even if lack of rain wasn’t necessarily linked to climate change.

The coverage of the links between animal agriculture, climate change, and dietary choices has also proved fertile ground for audience relevance. In May 2018, The Guardian summarized on its front page a study exmaining the environmental impact of commercial farms in over 100 countries with the headline “Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth.”

The article was liked, shared, or commented on more than a million times on Facebook. In similar fashion, the BBC designed a climate change food calculator, based on the same research, to assess an individual’s carbon footprint from their diet. And The New York Times published an interactive guide on the same topic, combining explanations and solutions, the individual and the global, and a fun gaming element.

Another example is coffee. Over two billion cups of coffee are calculated to be consumed in the world every day, with 150 million U.S. citizens drinking a “cup o’ Joe” on a daily basis. People clearly care about coffee. So no surprise when journalists choose to headline the dangers to your daily cuppa.

2. Out of the environment box

Editors and observers have long argued that climate change should be a story that cuts across many beats and issues, and particularly business and health. There does seem to have been an increase in new, innovative angles on the climate story.

Take sports for example. Recent coverage has included discussion of increased rainfall affecting cricket matches; the rugby-playing Pacific islands losing their islands; hotter temperatures at the Australian Open, Olympic host locations being chosen with climate change in mind; and mountaineers in the Himalayas having to remove the dead bodies of climbers as the ice melts.

Getting climate change into weather sections seems a helpful direction, too.

3. Potential solutions

Research into four leading U.S. newspapers showed that, in the past climate impacts and actions to address climate change were more likely to be discussed separately than together in the same article. And the ubiquity of doom and gloom portrayals of climate change, some argue, can be an obstacle to personal engagement and empowerment.

In the past, positive adaptation stories were hard to come by, representing less than 2% of all climate stories.

But solutions journalism seems to be gaining more traction in the climate field, which many advocate as an essential editorial corrective. For example, journalists belonging to the Earth Journalism Network are among many in the Global South who have covered successful attempts at adaption by poor communities, including fishermen and women in India using science and technology to warn them of approaching cyclones, and women farmers in Bangladesh finding new ways to adapt to increased salinity in the soil.

4. Multimodality, with a particular emphasis on visualization

Several organizations are blazing a trail in this space, including Yale Climate Connections with short audio reports, Vox and Deutsche Welle with video explainers, and The New York Times with strong, photo-led coverage such as this report on this report on ghost forests.

Carbon Brief has a strong track record on infographics, combining rich and complex science told in a comprehensible way with opportunities to engage with the facts. The science behind extreme event attribution is one example; the transformation of the UK’s energy supply is another. The Guardian’s recent timeline on the responsibility of the 20 largest fossil fuel companies is another powerful visual representation.

5. From global to local

For a long time, journalists have been pressed to find a local angle to their stories. The recent BBC’s infographic on translating the global 1.5C target down to the city level is exemplary, as is the Carbon Brief chart on which it was based. And a similar interactive map on how U.S. cities will be affected was hosted by Vice.

But perhaps the prize goes to the coverage of how climate change is affecting local people throughout Norway put together by journalists at the state broadcaster, NRK. Called “The Hunt for Climate Changes,” they tell the story of how climate change is affecting landscapes and groundwater color now, and is not something to fear in the future.

“It’s an example of strong, mobile-driven, visually-based storytelling, with people, emotions and (new) science information all embedded,” says Ingerid Salvesen, a journalist and teacher at Oslo Metropolitan University. NRK’s report was unusually popular online and on social media.

These choices and criteria are necessarily selective, subjective, and mostly in legacy English-language media. But they aim to give a flavor of how climate journalists are introducing new forms of quality reporting. Much of this is driven by the imperative of share-ability on mobile phones and social media, which puts a premium on engagement, fun, and strong infographics and other visuals.

Perhaps one element needs more attention. The report—by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—on impacts of global warming of 1.5 degree C. above pre-industrial levels speaks of the unprecedented societal change needed. So more coverage that examines the impacts of daily living would deepen the discussion of how to achieve lifestyle changes, and the role that different types of climate information may play in that transition.