In the month leading up to the election, Kevin J. Miyazaki and Mary Louise Schumacher load their "This is Milwaukee" publication into a newspaper box reimagined by Milwaukee artist David Najib Kasir

Being in a battleground state has meant having an embattled relationship with the news during the election season. As recently as this past weekend, President Donald Trump counted my hometown, Milwaukee, “among the most dishonest political places,” as a retallying of the votes in Wisconsin confirmed President-elect Joe Biden’s win.

In recent months, text and email alerts have flooded my phone, and my social feeds have been engorged with calls to action. Rabbit holes of disinformation have opened up online, too, universes of conspiracy theories, collections of sources that seemed to reinforce one another. It was so wearying that in the final days and hours before the election I put my laptop and persistently pinging phone in a drawer.

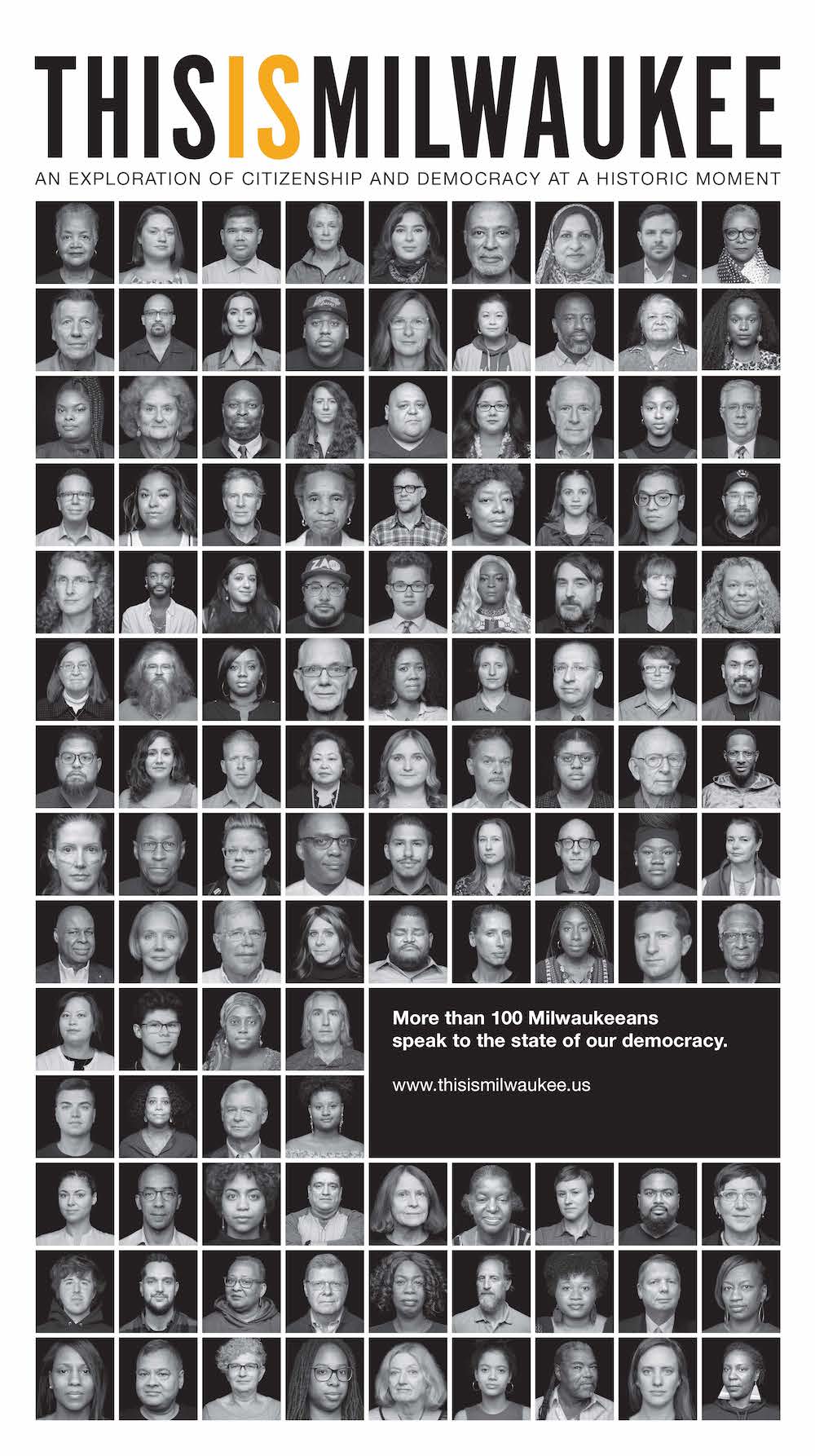

When Election Day arrived, I went to the polls to hand out copies of the “This is Milwaukee” publication, the final act of an 18-month project designed to inspire deeply personal reflections on democracy and a collaboration with artist-photographer Kevin J. Miyazaki. The 12-page newspaper we produced showcased more than 100 Milwaukeeans — schoolchildren, pastors, teachers, refugee advocates, restaurant owners, artists, community gardeners, kind neighbors, and others — people who embody citizenship in a painfully divided community, a place that is politically polarized and racially and economically segregated.

The project was also an experiment in journalism that helped me articulate some of the questions I have for myself and for our field in this norm-shattering time — about our values, the unprecedented challenges we face, and some old codes in need of reexamination.

“Would you like a free publication about democracy in Milwaukee?” Miyazaki and I asked, excited to put the papers into people’s hands, a gift for getting to the ballot box. Most people were delighted and even surprised to get our publication, produced in English and Spanish, at the dozen or so polling sites we visited. Some stopped to look at all of the faces on the cover. Scanning for neighbors or friends is natural in a not-so-big city. Some perused excerpts of interviews inside or the article that summarized some of what we learned, including that many Milwaukeeans believe democracy is at risk.

Others, though, didn’t want one more piece of media to be bombarded by.

The cover of the "This is Milwaukee" newspaper, showcasing the reflections on democracy by Milwaukeeans

“Oh honey, I don’t need any more junk in my life,” said one woman, quite kindly. We got a number of responses like that, and I confess, thinking of my tucked-away devices, I related to the sentiment. It made me think of all the people I know who — out of protest or a need for self-care — have vowed to turn off the news now that the election is over, to stop doomscrolling news of recounts, Trump’s ongoing baseless claims of voting fraud, and the valiant and now long-suffering tracking of presidential lies, more than 23,000 of them at the time of this writing, according to The Washington Post.

This most consequential of elections, which set records for levels of participation but also demonstrated how profoundly divided we remain as a country, may be over. But the equally consequential questions raised for media aren’t going away. Here are a few that keep me up at night:

What do we do when a drop of disinformation can cloud the truth so effectively?

How do we capture people’s attention meaningfully — or at all — in digital spaces where people are manipulated and overwhelmed?

What happens to local reporting when personality-driven, national news dominates?

Does horse-race journalism, so focused on winners and losers, contribute to the reductive and dehumanizing ways we see each other in our polarized time?

How and when should media take a stand and set the agenda?

If there’s anything I took away from spending a year and a half asking a single core question — “What is democracy, for you?” — it’s that there’s value in exploring the most critical questions of our time in a sustained way. Our project was a modest one, but it demonstrated how a community conversation can develop and evolve over time across various forms of difference, including political difference. At least for some, it provided a respite from a rapidly churning news cycle in which controversies explode and evaporate in turns. It was journalism that slowed us down, that we could hang onto, that inspired thoughtfulness.

Another takeaway from the “This is Milwaukee” project was to witness how many of us, myself included, romanticize democracy, stridently at times. We have the language down. We have our pat answers. We express a lot of certainty. And yet our ideas and definitions don’t always hold up when pressed. Many of our subjects, for instance, could talk about democracy as an idea but were challenged to discuss it in the context of their own lived experience. There is a profound need to dig deeper into what we think we know about civic life and society.

We mythologize the role of journalism within democracy, too, noting the importance of an informed electorate. But I wonder: Is that the best or only reflection of our values as a profession today? Could our job also be to plumb essential and sometimes uncomfortable questions, to help one another think and reason together and in a sustained way? This is also part of the project of democracy, as Harvard political philosopher Michael J. Sandel sometimes argues.

What would happen if a daily newspaper, for a year or so, devoted the pages of its features section to the question, “What does it mean to be an American today?” and the essays, ideas, books, films, artworks, music, memes and binge-worthy TV that are accumulating, directly and indirectly, around that question in this remarkable time? What if reporters did a deep dive into the question “What should a representative government look like today?” and gathered their communities around such discussions.

The problem with journalism that runs long and deep, though, is where it can lead, to strong points of view, advocacy and more mission-driven work — which journalists tend to avoid. The last few years have led me to rethink some of the ethical rules I followed as a newspaper journalist for more than 20 years, rules rooted in a laudable desire to serve all readers with their varying perspectives.

That code — to be objective, to keep political perspectives to ourselves, to forgo yard signs and bumper stickers — seems too simple now, a time when the notion of truth is itself under attack. Indeed, I wonder if such rules provide cover for editorial cowardice in certain circumstances, for avoiding difficult and challenging journalism. How many of us do ambitious, important but fundamentally uncontroversial work in an effort to steer clear of taking a stand?

Perhaps instead of being neutral we should be truthful, fair-minded, transparent and human. Not everyone will agree with this or draw lines in the same places. But if we do take on the essential questions of the day, we should be prepared to draw those lines, cautiously and with much consideration, rather than avoiding them altogether.