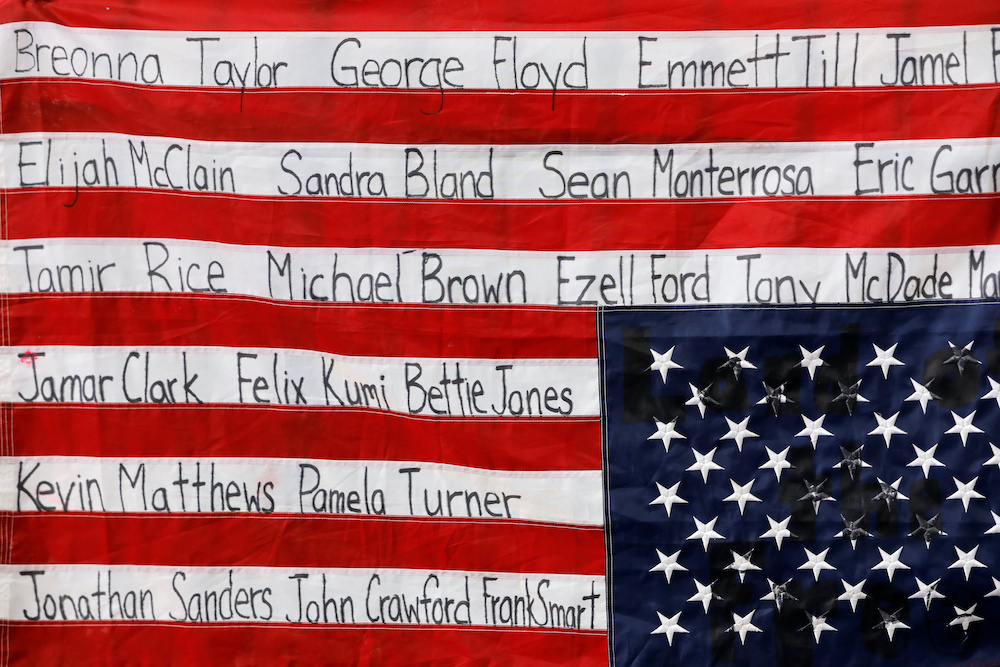

An American flag featuring the names of Black people killed by police is seen hanging at a protest to defund the police in New York City in June 2020

Newsrooms around the U.S. posed that question as largely white pro-Trump rioters and white supremacists, incited by the president himself, stormed the Capitol, waving Confederate flags and Trump 2020 banners, vandalizing the building, and threatening lawmakers. The mob quickly overwhelmed police, some of whom posed for selfies or gave fist bumps to the insurrectionists. Five people died in the melee, including one Capitol Police officer.

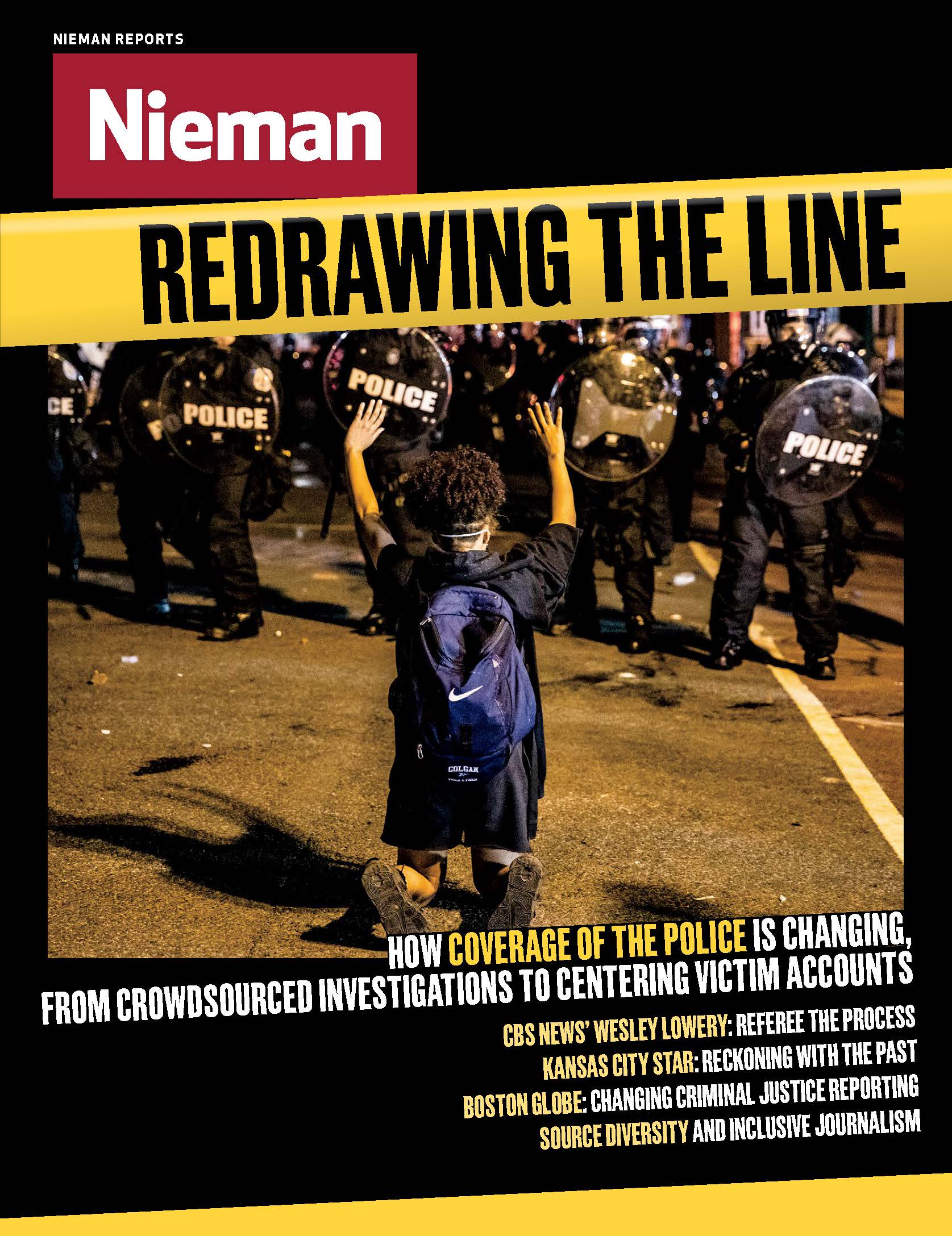

Coverage of police violence needs to change — and there are some signs that it is

Compare the police response on January 6 with the overwhelming force federal law enforcement used against the diverse group of people who gathered outside the White House on June 1 to peacefully protest the police killing of George Floyd, and consider the acts of brutality committed by police at Black Lives Matter protests across the country this past summer.

Many journalists were quick to call out the double standard, a sign of growth in newsrooms. Last summer some news outlets wrongly cast BLM protestors in broad strokes as rioters and looters. But the killing of George Floyd by Minnesota police officers in May and the national uprising against police violence and anti-Blackness that followed has prompted a reckoning in newsrooms, many of which have audited their race coverage, launched initiatives to rethink how their past crime coverage impacted communities of color, and held themselves accountable for their failures. It’s time to do that for coverage of police, too.

Journalism plays an influential role in uncovering and framing state violence and systemic oppression. But journalists also have a history of stoking the trauma and disrespect suffered by families when police kill their loved ones and of privileging police accounts above those of police violence victims and their loved ones. It’s a harmful pattern that, in the Black community, has increased distrust of both the media and the police. Newsrooms often fixate on the moment of death, leaning heavily on police narratives, and — as those narratives often do — assassinate the characters of police violence victims, such as when The New York Times reported, in the wake of police killing Michael Brown in 2015, that the teenager was “no angel.”

Coverage of police violence needs to change — and there are some signs that it is.

A new coverage dynamic is emerging. Outlets are crowdsourcing video investigations of police use of force, centering accounts from demonstrators and police violence victims rather than police accounts and concerns about property damage. Newsrooms are taking an interdisciplinary approach to reporting, scrutinizing, for example, the relationship between tech corporations and police monitoring activists’ social media feeds. And reporters are telling more in-depth stories about victims of police violence, without fixating on the killing or digging into the victim’s past to highlight criminality.

In live-stream footage captured by alt-right personality Tim Gionet, aka “Baked Alaska,” a police officer fist bumps a man who was among those who stormed the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C., on January 6

Context is key. Police violence doesn’t just happen. We live in a society that creates the conditions for police violence, especially against Black people. Police are part of a system in which Black people live disproportionately in segregated, economically disinvested, over-policed communities ravaged by mass incarceration.

These problems are compounded by the fact that newsrooms are rarely as diverse as the Black and brown communities in which they work. Many journalists consider public service as their mission, but large swathes of the public feel ignored by us. Journalism also perpetuates harm through stereotypical portrayals of marginalized groups, by mischaracterizing the nature of anti-racist efforts — or ignoring them altogether — and by reporting injustices without historical context or critical framing.

In too many cases, we have focused less on demonstrators’ concerns or treatment by police and more on aspects of protests that might inconvenience or scare audiences, like blocking rush hour traffic, damaging property, or displaying other “violent” behavior. Journalists have also gotten it wrong in accounts of police violence. As noted by Media Matters, coverage of Breonna Taylor’s killing “branded her a ‘suspect’ and sanitized police violence.” One of the most powerful things I’ve read about Breonna Taylor, or any police shooting victim, was when journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates decided to get out the way and let Taylor’s mother speak her truth in a told-to piece published in Vanity Fair.

Black journalists are having this reckoning, too, as explored by KPCC and LAist data editor Dana Amihere in her first-person piece, “Conflicted: A Black Journalist’s Reckoning With Her Race, Family And Police Brutality,” which describes her growing consciousness around the connection between police brutality and other institutions. “If we scorched the earth, we’d have to burn a lot of things down — mass incarceration, the war on the drugs, the inequities in health and education, they’re all part of the same problem — and it comes back to institutional racism,” says Amihere, whose family includes members of law enforcement and who is married to a white man.

The BLM movement, and the change it is prompting in newsrooms, challenges journalists to write about police violence in ways that center the perspectives of the individuals and communities most impacted, look more holistically at public safety beyond cops, uphold the dignity of the person slain, whether they are accused of wrongdoing or not — and address the harm perpetuated by coverage that fails to do these things.

Avoiding Extractive Relationships

Even before the Capitol invasion, BLM protests had put police tactics on display at levels previously unseen. On June 23, the Chicago Reader published “Cops appear to violate use-of-force rules dozens of times at protests” in collaboration with the Invisible Institute, a small nonprofit investigative newsroom based on the South Side of Chicago. “A lot of the initial reporting of what happened in those days of protest emphasized looting and emphasized injuries to officers. But the aspect of police violence didn’t get picked up or treated the same way,” says Andrew Fan, the Invisible Institute data reporter who led the project. “There was a feeling that we needed to find a way to put that part of the narrative in the conversation.”

Fan worked with colleague Dana Brozost-Kelleher to compile video from the protests, capturing more than 80 baton strikes on some 32 people that appear to violate Chicago Police Department policy. While baton strikes don’t always make headlines, the story notes they “are one of the most serious types of force available to officers.” The department considers strikes to the head and neck as deadly force, so the measure is only allowed to be used rarely under CPD policy, says Fan. The department unveiled a new baton policy in February of last year as part of the consent decree, the CPD’s reform process that is overseen by a court. The new rules “outlined limits on when officers could use batons and emphasized de-escalation and providing warning to civilians before resorting to baton strikes,” according to the story.

Demonstrators rally in the Logan Square neighborhood of Chicago in May 2020, protesting police brutality following George Floyd’s death

A video from May 31 in the affluent River North community shows cops advancing on an apparently peaceful protest, “possibly in response to insults from the crowd,” the piece notes. As one witness said, “They just lifted up their batons and started swinging.” “What was striking with so many of these videos was cops hitting people directly, repeatedly, in situations that did not in any way seem to warrant it, with their batons,” Fan says. After publication, the CPD emailed a statement to the Chicago Reader that read, in part: “Sanctity of life and de-escalation serve as the cornerstones of the Chicago Police Department’s (CPD) use of force policy. Any incidents of excessive force from CPD members are not tolerated, and if any wrongdoing is discovered, officers will be held accountable.”

The project would not have been possible without crowdsourcing and engaging with the community. In response to posts on Twitter and Instagram, the Invisible Institute received around 60 videos. When doing this kind of reporting, Fan says it’s important to avoid “extractive relationships” with police violence victims that mine their stories without being clear about how the reporting will provide value to their community and without reporting back to the community directly when the story is done to get feedback and respond to concerns or other information needs. Continuing a relationship with — and providing value to — sources and readers are central to Invisible Institute’s approach.

Part of this community exchange involves the Citizens Police Data Project, which the Invisible Institute manages and includes more than 230,000 pages of Chicago police complaint documents stretching back decades. Users can access the tools to look up any CPD officer’s record and past claims that they’ve used excessive force. Fan has seen organizers use the data to call out officers for their records, in some cases to their faces. “We’re doing this reporting where we’re asking people to share stories. We also have ways that we can help people, give people tools as they’re going to things like protests,” Fan says. “We want to emphasize that back and forth relationship.”

The Invisible Institute avoids reporting that only asks police violence victims about the impact violence has had on their lives but not about solutions to their case or broader systemic problems. Reporters also talked with organizers about the issues they were fighting for, raising questions about the viability of police reform in Chicago.

Fan acknowledges challenges to this approach. The Invisible Institute admits in the June story that “our review of video footage cannot conclusively assess the officers’ use of force,” but “in most cases we were able to assess the circumstances that preceded officers using force.” Going through so many videos of police violence is a slow, arduous, and emotionally triggering process, in which there are ethical challenges about whether to show people’s faces. Reporters had to ensure that protesters consented to be identified.

Black organizers and left-leaning activists have, in fact, long worried about becoming targets of state surveillance or other retribution, making some reluctant to be identified in pictures or named in stories. Social media has exacerbated such fears, which is why many organizers are wary of tweeting about their actions.

Social Media and Surveillance

These concerns speak to a strong connection between police surveillance, social media companies, and firms like Dataminr, an artificial intelligence startup that provides its customers, including government agencies, with information about global crises and news events. The Brennan Center, a nonpartisan law and policy institute, notes that social media surveillance “poses risks to privacy and free expression, increases disproportionate surveillance of communities of color, and can lead to arrests of people on the basis of misinterpreted posts and associations.”

The Intercept and other outlets have shed light on how police departments watch civilians online and how they target communities of color. Many of these stories have come from technology reporters, not journalists on the cops beat. As outsiders to the police beat, technology reporters bring an interdisciplinary and intersectional approach that provides a window into this underreported aspect of policing. In his July investigation for The Intercept, technology reporter Sam Biddle demonstrated how domestic surveillance amid the uprisings shows collaboration between police and Dataminr at a time when BLM protestors, as Black liberation activists before them, fear being targeted.

The Intercept and other outlets have shed light on how police departments watch civilians online and how they target communities of color

The catalyst for the story was staff researcher W. Paul Smith, who requested and quickly received emails from the city of Minneapolis containing correspondence with police about the protests after George Floyd was killed. The emails included two 5,000-page PDFs full of notification emails from Dataminr. “It became pretty clear that they were systematically keeping tabs on what was happening in the protests and scraping up a lot of people who were engaged in completely legal, completely peaceful, completely First Amendment-protected activities, either participating in or documenting the protests,” Biddle says. “It just struck me as something that people should know.”

Both Dataminr and Twitter — an early investor in Dataminr, as was the CIA — denied reports back in 2016 that the social media platform was being used to enable domestic surveillance. Among other measures meant to respond to criticism, Twitter said Dataminr, one of its official partners, would “no longer support direct access by fusion centers” that share intelligence between local, state, and national law enforcement agencies. But as Biddle reported, “Dataminr continues to enable what is essentially surveillance by U.S. law enforcement entities.” The story alleges that Dataminr wired tweets and other social media content about protests directly to police across the country, which it wouldn’t have been able to do without privileged access to Twitter data. Both Dataminr and Twitter have denied that the protest monitoring described in Biddle’s reporting falls under the definition of surveillance, and Dataminr maintains that its work is not meant for surveillance but aims to produce news alerts for emergencies like fires, shootings, and natural disasters, according to The Intercept.

As the protests were happening and Biddle was reporting his story, “a big dump of police fusion center data got put online,” he says. The “BlueLeaks” documents and data were hacked from more than 250 police websites and made public by activists, representing what The Intercept calls “an unprecedented exposure of the internal operations of federal, state, and local law enforcement.”

The BlueLeaks documents allowed Biddle to corroborate some of his reporting. He compared public records requests with the leaked government records, showing how police benefited from the special relationship between Dataminr and Twitter by getting alerts from Dataminr. “People should know what the risks are,” Biddle says, especially given the supportive public stance Twitter has taken in the BLM movement. “They are vocally presenting and being supportive of this cause, and here they are enabling surveillance of that cause.”

For some organizers, surveillance represents a type of violence in itself. Black activism and mass resistance to anti-Black racism have historically been treated as a threat to national security by federal law enforcement. The FBI has a history of surveillance of Black activists, so surveillance stokes fear that the government is targeting them. Indeed, The Intercept reported in early June that several people in Tennessee were “intimidated at home and work” and questioned about Antifa after posting on social media about BLM rallies.

But it’s not just the FBI that organizers are concerned about. Biddle showed evidence of local police departments monitoring social media with help from the private sector. In August, PublicSource, a Pittsburgh-based nonprofit digital newsroom focused on public service reporting and analysis, reported that Pittsburgh police used social media to identify and compile evidence against suspects in crimes allegedly related to BLM protests. Pictures of protestors taken from social media were compared to a website that has a database of driver’s license photos and photos from correctional agencies and other criminal justice institutions. A public information officer for the Pittsburgh Police Department told PublicSource in an email statement that the department “does not own the technology,” but that law enforcement agencies throughout Pennsylvania had access to the tool.

But social media monitoring isn’t a black and white issue. While this type of intelligence work has been misused to target people of color as part of police surveillance, social media posts are also being used to identify the perpetrators of the Capitol siege. That might seem difficult to reconcile but it shouldn’t be, because any tool — or system — can be used to benefit or disadvantage particular groups. Some might argue that the tool itself should be abandoned given its potential for harm; others just want the tool to work well for them, not against them.

Biddle remains concerned about police surveillance hiding behind “private sector curtains,” especially if police outsource this work to the private sector, with companies prioritizing profit and not being held accountable to the public. “To me, that’s the bigger picture problem,” he says. “You have the immediate harms of undue police scrutiny and police surveillance, but then there’s just a bigger question of, why should we be having companies that are accountable to a boardroom doing the police’s dirty work?”

Police in riot gear stand in formation during protests against police violence against Black people in May 2020 in Louisville, Kentucky

In October, Biddle reported that Dataminr was targeting communities of color, writing that “company insiders say their surveillance efforts were often nothing more than garden-variety racial profiling, powered not primarily by artificial intelligence but by a small army of human analysts conducting endless keyword searches.” Biddle spoke with sources inside Dataminr who suggested Dataminr has sometimes used “prejudice-prone tropes and hunches to determine who, where, and what looks dangerous.”

One service Dataminr provides to police is flagging potential gang members, information compiled by poring over social media, that police can add to their databases. Critics say the databases are poorly kept, riddled with errors, and based on factors like the criminalization of children, overly harsh sentencing, and biased policing. In a written statement sent through a public relations firm, Dataminr said it “rejects in the strongest possible terms the suggestion that its news alerts are in any way related to the race or ethnicity of social media users” and denied its actions constituted surveillance.

The Environmental Portrait Approach

Washington Post reporter Arelis R. Hernández was talking to residents in the public housing projects in Houston’s historically Black Third Ward neighborhood, where George Floyd grew up, after covering his funeral, when she had a thought: “I would hate for the story of George and of this community to be one-dimensional, or the story of George’s life to be only about his death.”

Hernandez had a conversation with someone named “Miss Cookie,” who lived in the neighborhood. That conversation didn’t initially seem like story material, but then the woman said that when she saw what happened to Floyd she saw her son. “She was basically preaching on her porch, and I was there to listen,” Hernández says. “And that conversation on her porch stayed with me for a long time. When I came home from Houston, I couldn’t shake it.”

Hernández — who grew up in Prince George County, a predominantly Black community in Maryland that, like the Third Ward, has a rich, complicated, and problematic history — got her news chops in Orlando working as a breaking news reporter. “You get good at finding people and information quickly,” she says. But she wanted opportunities “to get off the hamster wheel and ask: Why are we doing this? Can we go deeper?”

On the breaking news beat, Hernández spoke with many grieving families, learning that murder victims “are full people deserving of dignity and respect, and the story isn’t just about their death.”

Hernández brought that ethos with her to The Washington Post and to the massive reporting team behind “George Floyd’s America,” which focuses on his life and the many inequities and institutional injustices he suffered in his 46 years. The series explores the role systemic racism played in his life, from the subpar education system that failed him to the impoverished housing project and over-policed communities in which he lived to the companies and communities that profited from his prison stints and failed substance abuse programs. Hernández published a piece in the series in late October titled “A knee on his neck” that chronicles how “Police were a part of George Floyd’s life from beginning to end, an experience uncommon for most Americans, except other Black men.” She doesn’t describe Floyd’s death until the very end.

The story shows how Floyd, who had issues with mental health and addiction and struggled to maintain stable work, was apprehended frequently on minor offenses, made bail, and often took plea deals, part of what the piece describes as “a revolving door to jail.”

The idea for the series grew out of a decision among a group of reporters and editors working on police violence that they didn’t want to just ask what happened to George Floyd but why. The team tried to take what Hernández calls “an environmental portrait approach, where we’re asking questions in a way a daily story would not have rendered.”

“The team decided that we should take a step back and think about his life and what his life could tell us about systemic racism in this country,” says the Post’s managing editor of diversity and inclusion Krissah Thompson.

One challenge for Hernández was sorting through all the rumors about George Floyd’s life and what people thought about his death to get a more textured view. Hernández had to be careful to let the reporting lead her “and not any preconceived notion about what the story should say.” That meant immersing herself in the community that raised him and saving space for Floyd’s friends, family, and members of the community to speak their truths. Hernández had the benefit of time to build rapport rather than just parachuting in and out for Floyd’s funeral in Houston, talking to other community members about their experiences with police and systemic racism.

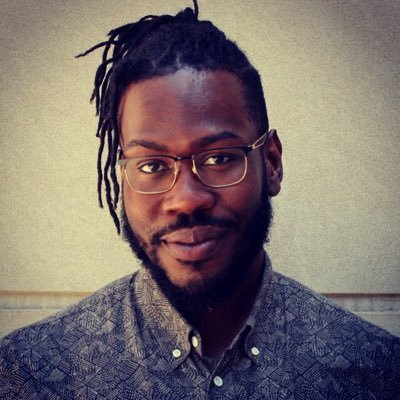

Journalists have a history of privileging police accounts above those of police violence victims and their loved ones

She looked up his court record, not to paint him as someone with a sketchy past, but to understand the role that police and the justice system had played in his life. Hernández also spoke with friends of his, including friends who witnessed Floyd’s legal issues and struggles to improve his life, to provide greater context. Her story also juxtaposes Floyd’s run-ins with the law with the Houston Police Department’s problems with racism, corruption, and police misconduct during Floyd’s life, including officers punished with probation for serious offenses like homicide and civil rights violations. It was hard getting that context from police, who were often unwilling to talk, but she eventually found a few Black former Houston police chiefs who acknowledged the issues and gave more insight into the challenges they faced trying to reform the department.

What kept the story on track was having a team passionate about the subject, time to collaborate, a project manager to coordinate multimedia, and dedicated editors like Thompson — who is from Houston herself, so had an ear for what is authentic from that place — who believed in the story. The project was also helped by the diversity of the reporters and editors working on it. “Diversity always matters, especially in tackling a subject like systemic racism; you want a variety of perspectives,” Thompson says.

News organizations often perpetuate injustice against “and further harm communities we’re attempting to tell stories about in neglecting to report on the formula for why things happen the way they do,” says Hernández. “The danger is that we rely on what we think is the conventional wisdom to explain why things happen, missing out on the role systems and institutions have on these terrible outcomes for people, particularly Black people and people of color. And the harm is we lose trust with the communities we cover.”