Newsrooms have long been the traditional space where young journalists learn to report on the job, so the loss of physical workplaces due to the coronavirus pandemic has had a particularly harmful impact on many journalists just starting out in their careers

Their learning curve was even sharper, given that they had to do it all virtually, from their homes.

Newsrooms have long been the traditional space where young journalists learn to report and work on the job

While Brindley, a union officer for her guild, thinks her team has done well to adapt, she notes that it wasn’t the same as working together in an office. “I used to eavesdrop on interviews that other reporters were doing over the phone and listen to them talk to each other about stories they were developing. It was the best learning experience as a professional reporter,” she says. “I can’t imagine starting as a reporter not having that experience right now.”

But now, at The Courant and elsewhere, they might have to.

Early in December the longest continuously running newspaper in the country announced it was shutting down its physical newsroom. Tribune Publishing, the company that owns the paper, and that in February agreed to be acquired by its largest shareholder, the hedge fund Alden Global Capital, said that “as the company evaluates its real estate needs” during the pandemic, it made the “difficult decision” to close the offices permanently.

The paper’s union put it in much plainer terms, tweeting: “This is what happens when hedge funds own newspapers.”

Newsrooms have long been the traditional space where young journalists learn to report and work on the job. At their best, they can foster the type of collaboration and mentorship necessary for good work. But, like any workplace, they can also be marginalizing and exploitative. With the loss of these physical spaces — either temporarily or forever, as the coronavirus runs rampant and the vaccine rollout falters — how are journalists just starting out in their careers now faring?

Reporters at the more than 250-year-old Hartford Courant had already been working from home since mid-March, messaging on Slack and taking virtual meetings through Microsoft Teams, but they had expected to eventually be back in the office when the pandemic was under control. Then, in October, Tribune announced it was outsourcing the Courant’s printing presses, eliminating 151 jobs from the Hartford offices. “I knew at that point the office was closing,” says Daniela Altimari, a statehouse reporter who has worked at the paper for more than two decades.

Still, when the official announcement came, it was a blow. “It felt like we had a light at the end of the tunnel,” as Brindley puts it. “Now that light is extinguished.”

As the pandemic forced media companies to close offices, journalists have had to pivot to working often entirely from home. While the closures are ostensibly temporary for many newsrooms, the Courant’s situation is not isolated; Tribune Publishing also permanently shut down five other local newsroom offices over the summer, including the New York Daily News and Florida’s Orlando Sentinel. At Columbia Journalism Review, Ruth Maragilt documented the trend, writing that “all across the country, the coronavirus was exacerbating a hollowing-out that had been underway in journalism for the past decade…The latest manifestation, catalyzed by stay-at-home orders, was the elimination of newsrooms.”

Zoë Jackson, a 22-year-old reporter at the Minnesota Star Tribune and Report for America corps member, moved to Minneapolis this past May to start her new job amid the pandemic and George Floyd protests. She felt lucky because she had interned at the Star Tribune the summer before, so she had already met and worked with many of the people at her office. But even with all that, Jackson says she still misses the incidental moments with colleagues: “I like co-working and being able to just walk to somebody talk to them, [to say], let’s get coffee and talk about this. I really miss that.”

It helps that Jackson’s current editor runs through her stories with her over video chat, and they do check-ins that are not work related. “I get to see her face and we get to talk about our lives separate from the work I owe her,” Jackson says. “I’ve been really appreciating that lately.”

For many, losing a newsroom means also losing the type of serendipitous conversations that can really help a young reporter

For many, losing a newsroom means also losing the type of serendipitous conversations that can really help a young reporter who might not have a big rolodex of sources or the same community connections. Altimari, the veteran Hartford Courant reporter, says that learning from more senior colleagues on the job was a big part of her journalistic upbringing. “We all learn from one another. Sometimes you’re working on a story and your cubicle mate overhears you and will say, ‘Did you talk to so-and-so; they’re a great source,’” Altimari says.

Even though veteran reporters and editors are often stretched thin, Altimari says when new reporters started at the desk she worked on it was easy for her to walk by and grab a cup of coffee to get to know them and their work. Now, those moments will have to be much more formalized.

Many young journalists in local newsrooms across the country recounted a similar loss. Some only talk to their direct editor or teams, which they feel limits their experiences in learning from people across the newsroom. There’s also a difference in being able to bounce ideas off people in person, versus having to do it over a video meeting.

Still, there are ways to adapt. Jackson’s Star Tribune newsroom and guild have been doing social events on Zoom, which, while at times awkward, has allowed her to see the faces of some people she hadn’t seen in nearly a year. Jackson especially appreciated one session where people came in to talk about working from home, recalling how colleagues shared how they’ve had to accept that 2020 was not their best year of work. “I’m like, wow, because I read your stories and I would never thought you felt like that,” Jackson says. “It makes me feel better hearing [them] talk about that.”

In normal times, young reporters might be able to build up sources by going to school board meetings and community events. Now, some are finding it hard to develop relationships with people in the community over the phone and social media. Megan Valley, a 24-year-old education reporter with the Belleville News-Democrat in Illinois and a Report for America corps member, says that connecting with parents has been a particular challenge. “If you’re doing a story about kids, it can be very sensitive. I think it’s a lot easier to build trust if you’re already someone people have seen around and maybe know,” Valley says. One photojournalist told me about how she’s had to adapt to photographing people in their homes from outside their windows.

Some young journalists have been able to get around these issues by leaning on social media and Google forms. Rachel Rohr, who runs training programs at Report for America, which places emerging journalists in local newsrooms, has organized workshops with seasoned reporters on topics from how to create sensory-laden scenes via phone interviews to how to develop sources during a pandemic, including tips like holding virtual office hours and events, flyering, and asking people from nonprofits who are still working in person to help connect you to the community.

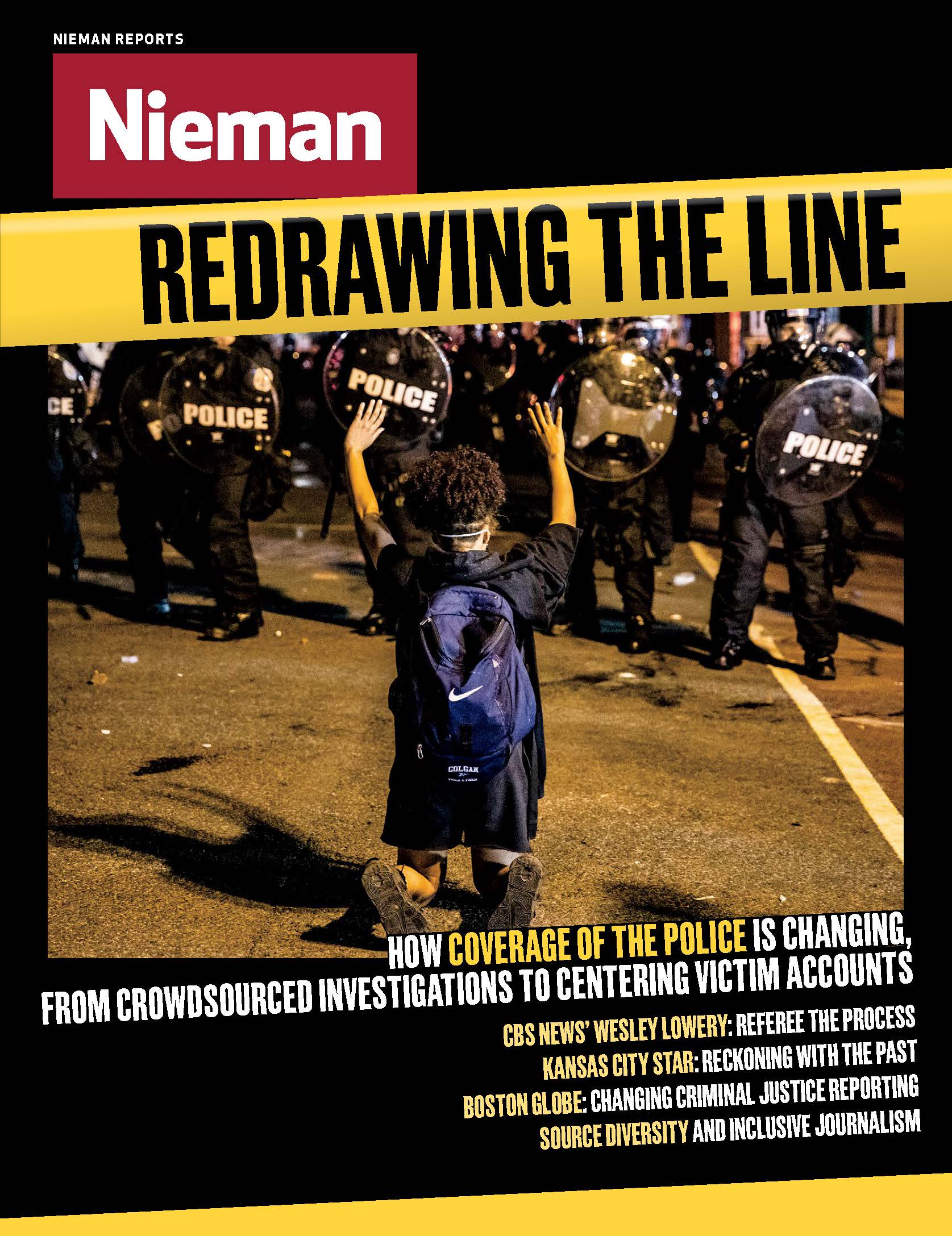

The mostly empty Hartford Courant newsroom back in March 2020, soon after most reporters and others began working remotely

And then there’s the mental health aspect of working from home, which has often meant people have worked longer hours with little delineation between work and home life. The normal isolation that comes with a pandemic is compounded for young journalists who might be moving to entirely new places where they’ve been lucky enough to land a job. According to one survey of 130 journalists by John Crowley, a freelance editor and media consultant, 64% of respondents said they hadn’t had any positive work experiences during lockdowns; 87% felt like their employer should bear some responsibility for their work-from-home conditions. Newsrooms should be providing material support, including subsidizing what people would normally have access to in an office, such as internet, phones, and office supplies that they need to do their work. They should also be flexible about all the obligations — like parenting or eldercare — that people might be juggling right now.

Newsroom shutdowns are only one new aspect that young reporters entering the industry during an economic recession face right now; tumultuous entries into journalism careers are becoming more common than not. The Courant itself has faced continual cuts over the years. Putterman says he was once talking to a more veteran reporter about his backup plan to journalism, should he ever get laid off. The older reporter said they had never thought about that when they were starting out. “It was jarring to me,” Putterman says. “Every young reporter I know has a backup plan.”

Like every workplace, newsrooms have their own issues. Institutional work cultures can be racist and sexist; many journalists of color face microaggressions both in physical and virtual workspaces. Younger reporters, who have less power in the newsroom, can often find themselves doing low-paid, entry-level work with uneven mentorship and training opportunities.

The current shift should be seen as an opportunity for newsrooms to reinvent themselves, according to Dr. Courtney McCluney, a professor of organizational behavior at Cornell University who studies marginalization in the workplace. The move to remote work should be a time for newsrooms to be intentional about “redefin[ing] what kind of workplace they want to have.” This means keeping the parts of the newsroom that worked and thinking critically about what needs to be changed.

And the flow of learning goes both ways — younger journalists, who are often in more precarious positions and come from a more diverse generation, have experiences that should inform newsrooms. In a piece on working from home while Black, McCluney and Laura Morgan Roberts write that one way managers can foster a more inclusive environment is to “relax their expectations for workers’ participation” right now. This could mean asking “everyone to join meetings using mediums that are based on their personal comfort level and accessibility that day.”

When it comes specifically to mentorship for younger employees, remote work environments often put the onus on individuals to reach out if they want to make connections with people outside their direct teams. “It would behoove newsrooms to create programs particularly at this time to tap into the existing veteran talent, to help continue to rear the emerging talent, formalizing and scheduling those opportunities,” says Sarah Glover, former president of the National Association of Black Journalists.

For editors, managers, and veteran reporters who are also dealing with burnout, overwork, and parenting during a global pandemic, it might be easy to forget about fostering their younger colleagues in the office. But as Megan Greenwell, editor of Wired.com and co-director of the Princeton Summer Journalism Program, points out, “That first job in an industry like journalism, which so many people drop out of, is in a lot of cases just totally make or break.” She notes that more senior members of the office reaching out to younger colleagues can go a long way and that finding more ways to connect, even virtually, feels “particularly important” right now.

Greenwell points to the mentorship program her company set up this summer where people were paired with others they didn’t work with on a day-to-day basis. Her mentee is someone she had never met before. “It’s so fun and I’m getting as much out of it as she is,” Greenwell says.

Newsroom shutdowns are only one new aspect that young reporters entering the industry during an economic recession face right now

In October, Andrea González-Ramírez founded the Latinas in Journalism Mentorship Program, which matches early-career Latina women and nonbinary Latinxs with fellow veterans in the industry. Many of the mentees were “feeling unmoored” as they started their first jobs or freelance careers during a pandemic, often as the only Latina reporters in their newsrooms, says González-Ramírez.

The program takes place mainly over Zoom and phone calls, but is off to a good start, according to González-Ramírez, in part because one of the most important things they were looking for when screening mentors was a willingness to commit a certain amount of time to the mentoring relationship. “One mistake I do feel newsrooms do when they have mentorship programs is that they just arbitrarily pair people up,” she says. “Something I’ve heard from mentors and mentees is, ‘I just had one call and never spoke with that mentor ever again.’” Instead, González-Ramírez argues newsrooms should be deliberate about who they pair up and why — and make sure they choose mentors invested in the project: “We want to make sure we can pair people up who can relate to each other in a more profound way than just, ‘Oh, we’re journalists. For example, there are intentional categories in our directory for people who are queer or immigrants or moms.”

The decimation of the news industry overall already makes it challenging for young reporters just starting their careers. The loss of physical newsrooms is a new fire to put out, amid a bigger fight for better working conditions, but most young journalists I spoke to expect to return to the office someday. Yet it still remains to be seen what will happen to the next generation of journalists when their newsrooms shut permanently and go fully remote, like the Hartford Courant.

Brindley worries that without a newsroom, more people at her office will try to find jobs elsewhere because they “feel like they don’t have a home.”

As for her own future? Brindley loves her work and serving the community she reports on but isn’t sure how sustainable it is in the long run: “I don’t feel like I have a reliable career path sketched out because I don’t think it’s possible to sketch out a reliable career path.”